One of the most remarkable cats I have ever lived with was an all-white female with one blue and one green eye. She was hard of hearing, though not deaf. She came to us from a local animal rescuer along with her sister; the pair, whom I named Kayley and Hayley, joined the large outdoor-indoor enclosure for homeless cats in our side yard.

The sisters made good lives for themselves for eight years, spending much of their time together. Kayley was the more adventurous, taking evident enjoyment in climbing to the top of green leafy bushes to bask and doze in the sun. She weathered the partial surgical amputation of both ears owing to cancer.

Then Hayley died of cancer. We laid her body on a tarp in the grass. Several cats sniffed at it briefly, but Kayley acted unlike anyone else. She stared long and fixedly at her sister from a short distance away. For the first time in her life, she was without her closest companion.

When more cats in the enclosure grew old and died, we brought Kayley indoors. Unwitnessed by us, she sustained a complex fracture of her femur, then escaped her carrier as we brought her home from the vet. Experienced cat caretakers, we felt guilty and terrible. For a month, we searched for her in wintry conditions, finding her at last, filthy, thin and hungry. Indoors again, she not only healed, but also warmed to living with us, reclining on our sunroom couch or inside a woven basket, prancing in place as we rubbed her neck. This summer, 13 years after she came to us, she died of abdominal cancer.

Kayley had her particular pleasures. She loved, and she grieved. She acted with strength and courage when faced with life challenges, I believe in part because she learned over time from her life experiences how to be resilient. After her death, while reflecting on these aspects of her life, I read these words by Kwame Anthony Appiah who writes the weekly ‘Ethicist’ column for The New York Times:

The quality of the life of a dog or a cat is a matter of the quality of its moment-to-moment experiences. They have no projects to complete; their lives have no narrative arc that matters to them.

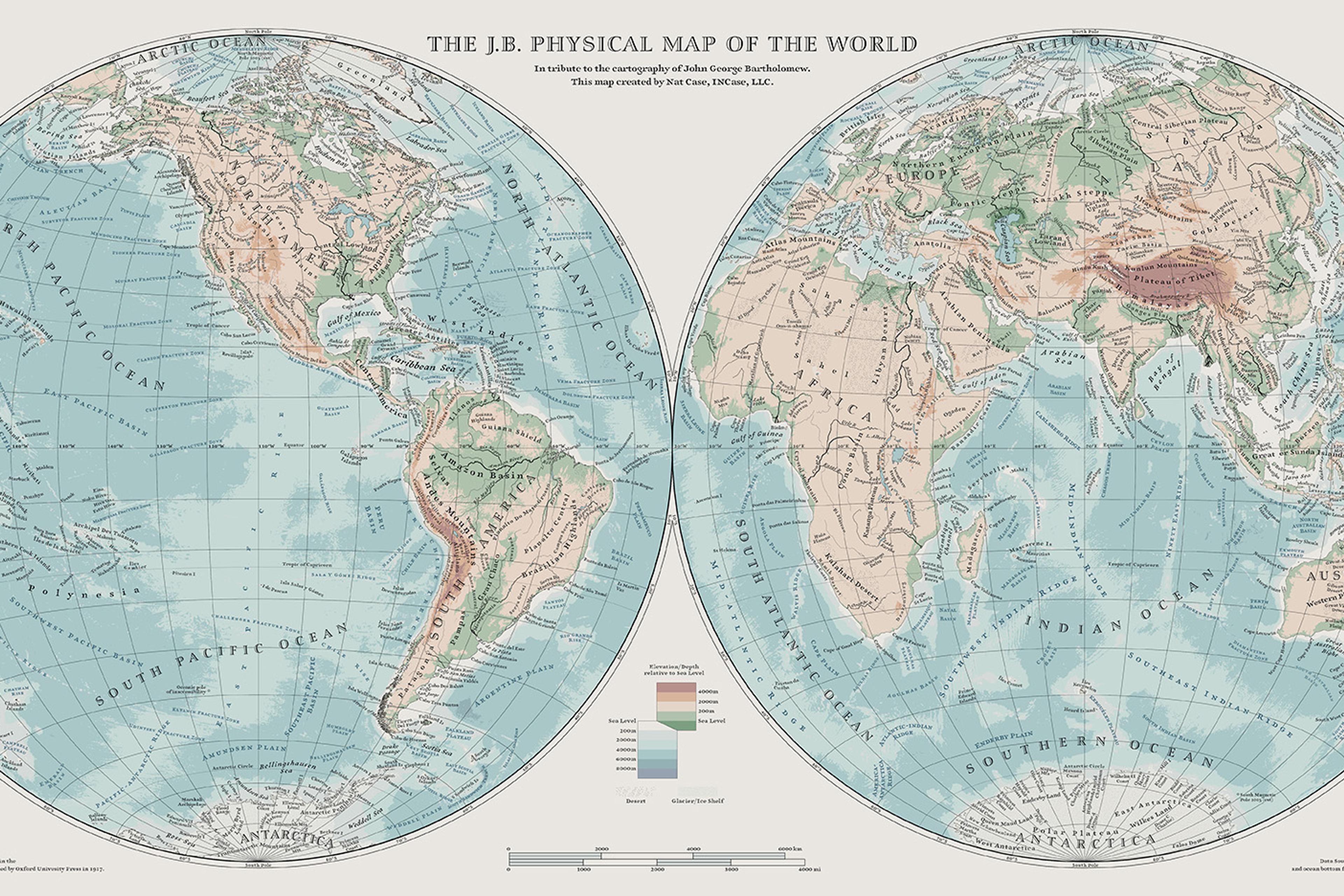

But what is a narrative arc? Writers define it as the sequence of events that unfolds in a story’s plot, the progression through beginning, middle and end. In our lives, too, a sequence of events, a story, unfolds over the years; what happens to us (or what we make happen) alters how we think and feel, thus setting a new platform for what happens next. Based on centuries of study into animal consciousness and learning, it’s almost certain that many other animals experience a meaningful arc in their lives too.

Appiah’s assertion that cats and dogs experience no narrative arc is an example of human exceptionalism. Human exceptionalism takes many forms but most share an assumption that our species displays singularly complex ways of being, thinking and feeling. On this perspective, other animals’ capacities are inferior, and so other animals’ lives are also seen as inferior.

It’s only a myth, though, that other-than-human animals inevitably live moment to moment. Many mammals and birds remember and learn from past experiences, and anticipate with joy or fear what may be coming next. Recognition of this fact threads throughout my most three recent books: a whole variety of animals express grief when someone they cared about and remember dies, including elephants, orcas, monkeys, giraffes, Canada geese, ferrets, cats and dogs. Fish, chickens, goats, cows and pigs solve problems in their lives and interact socially in ways that defy the possibility of being trapped in the present. And only when we humans recognise how vulnerable other animals are to the harms we cause them – because they remember the past, and wish to live in the present and future without trauma – will we act with full compassion for animals and make their lives better.

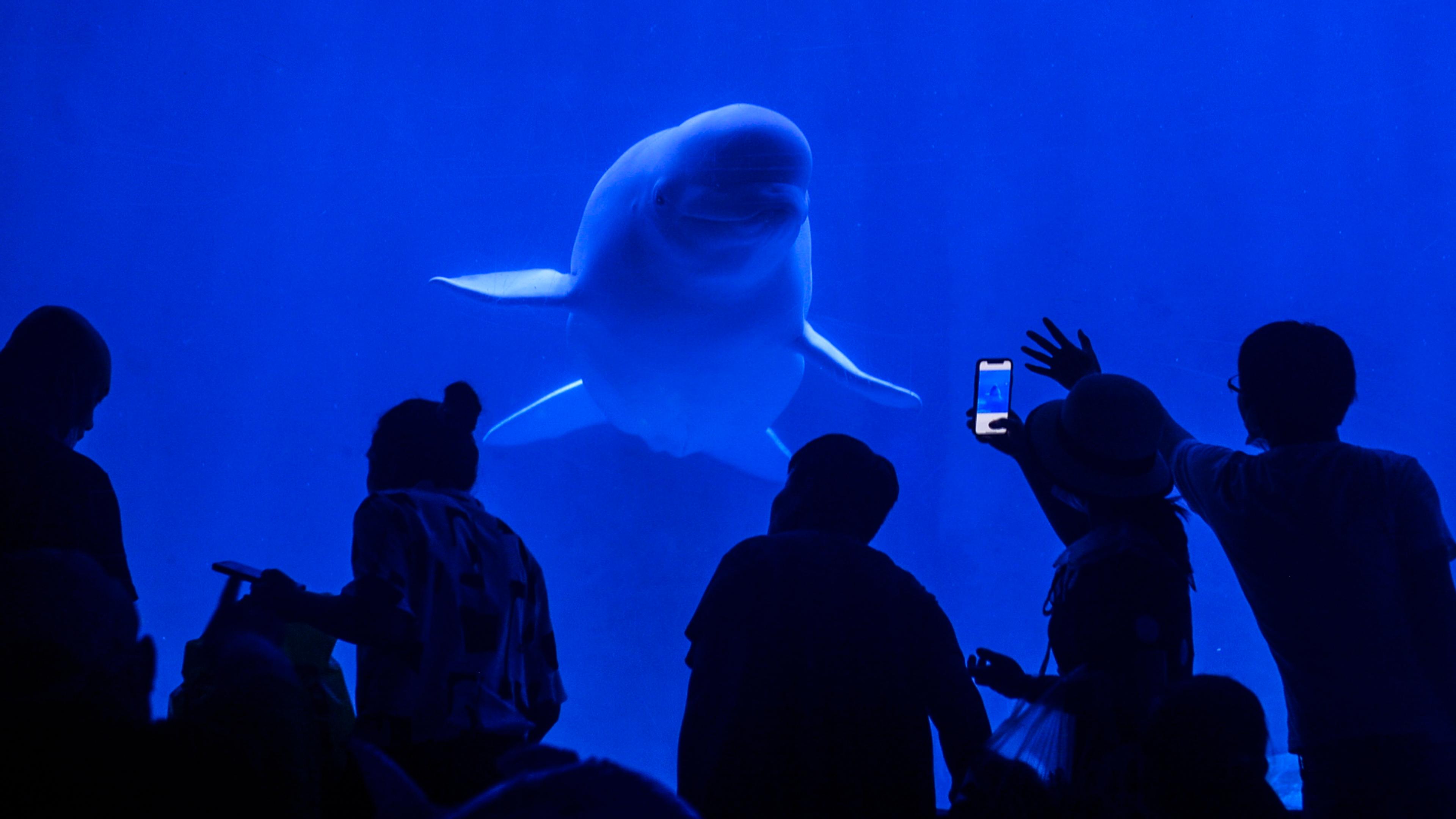

Over decades of research and writing in anthropology, I’ve come to see a central truth: when human lives are seen to be of ‘unique value’, it becomes that much easier to slaughter farmed animals for food; confine monkeys and rodents to suffering in research laboratories; and confine dolphins and whales in theme parks, where we ask them to perform tricks.

What horrible costs human exceptionalism imposes on other animals! We lose out, too. Genuine connection to other animals emerges when we try our hardest to truly see the ways they live and may express thoughts and feelings – including in ways that don’t mirror our own.

Recognising variety in other animals is central to moving beyond human exceptionalism. Elephants, chimpanzees, orcas and ravens have increasingly been described as tool-makers and tool-users, or as individuals embedded within cultural networks of learning and teaching. But occasionally, a different sort of animal captivates us so much that we are, happily, forced to stop using our own experience as the standard against which to measure others.

Octopuses made the list of animals in the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness document in 2012, and continue to reign in the media as the poster animal for invertebrate intelligence. Most descriptions explain that these cephalopods may use tools, cleverly escape their enclosures, or interact socially in complex ways. True, but what if we look further? Octopuses, after all, think with all eight arms as well as their brain, and flash moods on their skin. When I met a giant Pacific octopus kept at the New England Aquarium (where I wished he hadn’t been held captive), he chose to wrap one of his arms around one of mine. I just couldn’t understand what he was experiencing in that moment! What I did know was that this limitation was a human one; his experience of life wasn’t ‘inferior’ to my own.

Invertebrates, I think, are key to overturning human exceptionalism. I’ve written about spiders before. It’s wild and wonderful to learn that spiders think ‘despite having miniature brains’, as the biologists Samuel Aguilar-Arguello and Ximena J Nelson put it. When navigating their wild landscape, salticids or jumping spiders must sometimes take detours as they head for a goal. ‘Detouring,’ these authors write, ‘is an elaborate cognitive process, as it implies route planning after assessing several possible alternatives.’ When seeking prey is the goal, it may also imply memory and internal representation of the position of the prey. In certain salticids, ‘the spider can be out of sight from its prey for over 80 minutes’.

Other spiders think with their webs in ways akin to how octopuses think with their arms, as extensions of their brains. There’s even a tantalising possibility, emerging from the research of the behavioural ecologist Daniela C Rößler and colleagues, that jumping spiders dream. What else might spiders do that we currently cannot even imagine?

The study of animal dreaming is poised to offer a fresh push away from human exceptionalism. When cats or dogs sleep, their eyes may move behind closed lids and their paws twitch, perhaps accompanied by whines or growls. Are they dreaming of rolling or playing in the grass? May we ever know?

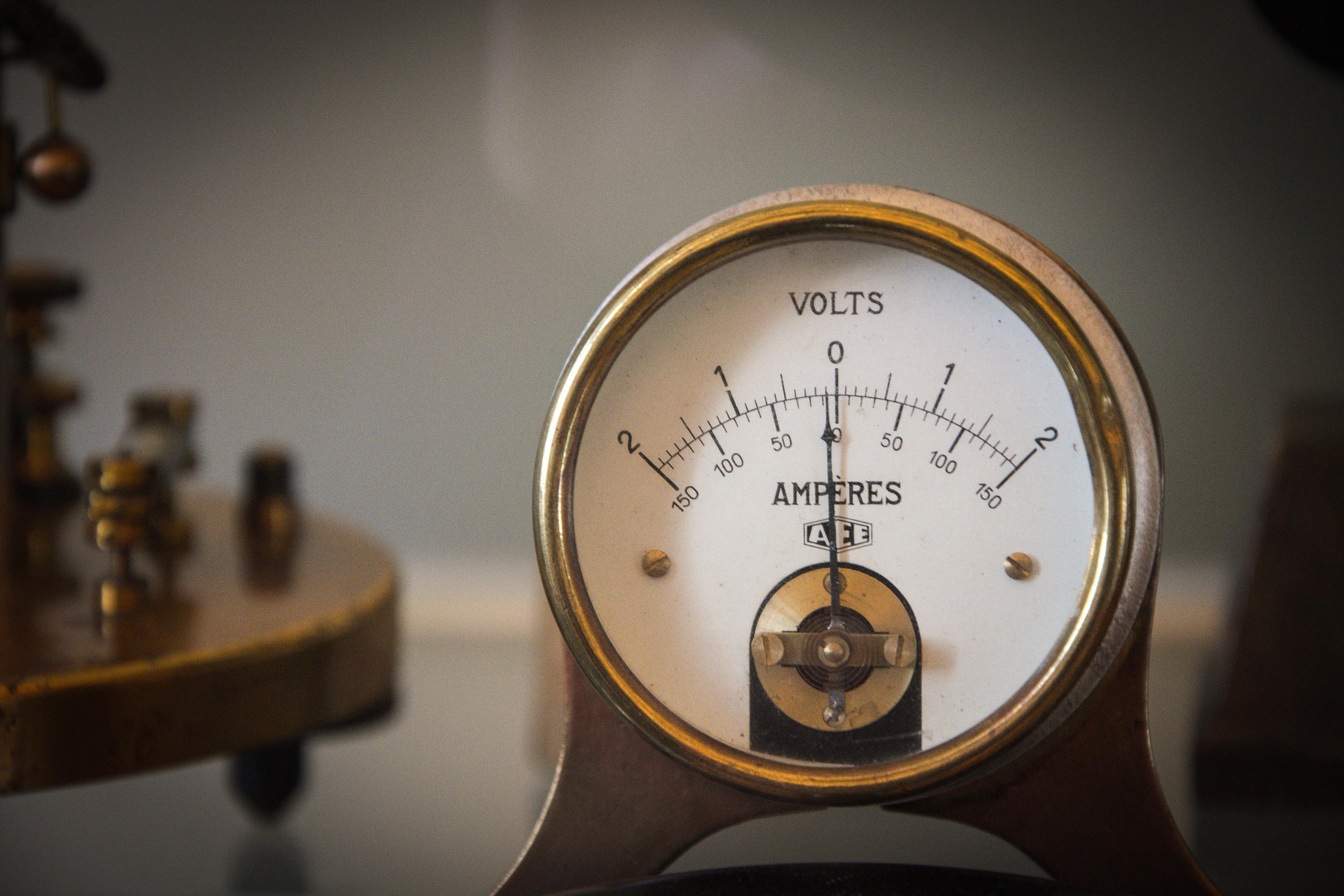

Answers to this question come in David M Peña-Guzmán’s remarkable book When Animals Dream: The Hidden World of Animal Consciousness (2022). Describing the work of the neuroscientist Freyja Ólafsdóttir and colleagues – who had rats run a maze with food treats blocked off; then nap; then run the maze again with the blocked area opened and the food treats removed – Peña-Guzmán writes:

The same hippocampal cells fired – and fired in the same order – when the rats slept after seeing but not physically exploring the cued arm as when they explored this arm after their nap. The rats had had an emotionally exciting experience and then ‘actively imagined a “future experience” in which their desires were fulfilled’.

What a spectacular discovery! Yet as someone concerned with animal rights as well as animal welfare, I can’t help but wonder how many animals have had bad dreams because of human exceptionalism. Laboratories, after all, can be nightmarish places – literally, it’s all too common in research circles to treat animals as expendable.

Rats made to participate in painful experiments sometimes startle awake from what can only be described as nightmares, according to Peña-Guzmán in reviewing research led by the pharmacologist Bin Yu. (How’s that for a heart-wrenching narrative arc?) Might laboratory animals like Cornelius, a rhesus macaque held in a research laboratory since birth in 2010, suffer from terrifying dreams? What about individuals like the distressed cow Luma seen in Andrea Arnold’s documentary film Cow (2021), animals who have their sons and daughters forcibly taken away from them at birth to support the dairy industry? Might they relive their losses in sleep?

I began this piece with a eulogy of sorts for Kayley, a cat whose expressions of thoughts and feelings I tried to understand and honour. Accepting these inner lives are a first step towards dismantling human exceptionalism. But animals who think and feel in totally opaque ways, or perhaps not at all, deserve our care, too. We owe it to all beings with whom we share Earth to construct a world that moves beyond human exceptionalism. We owe it to ourselves as well.