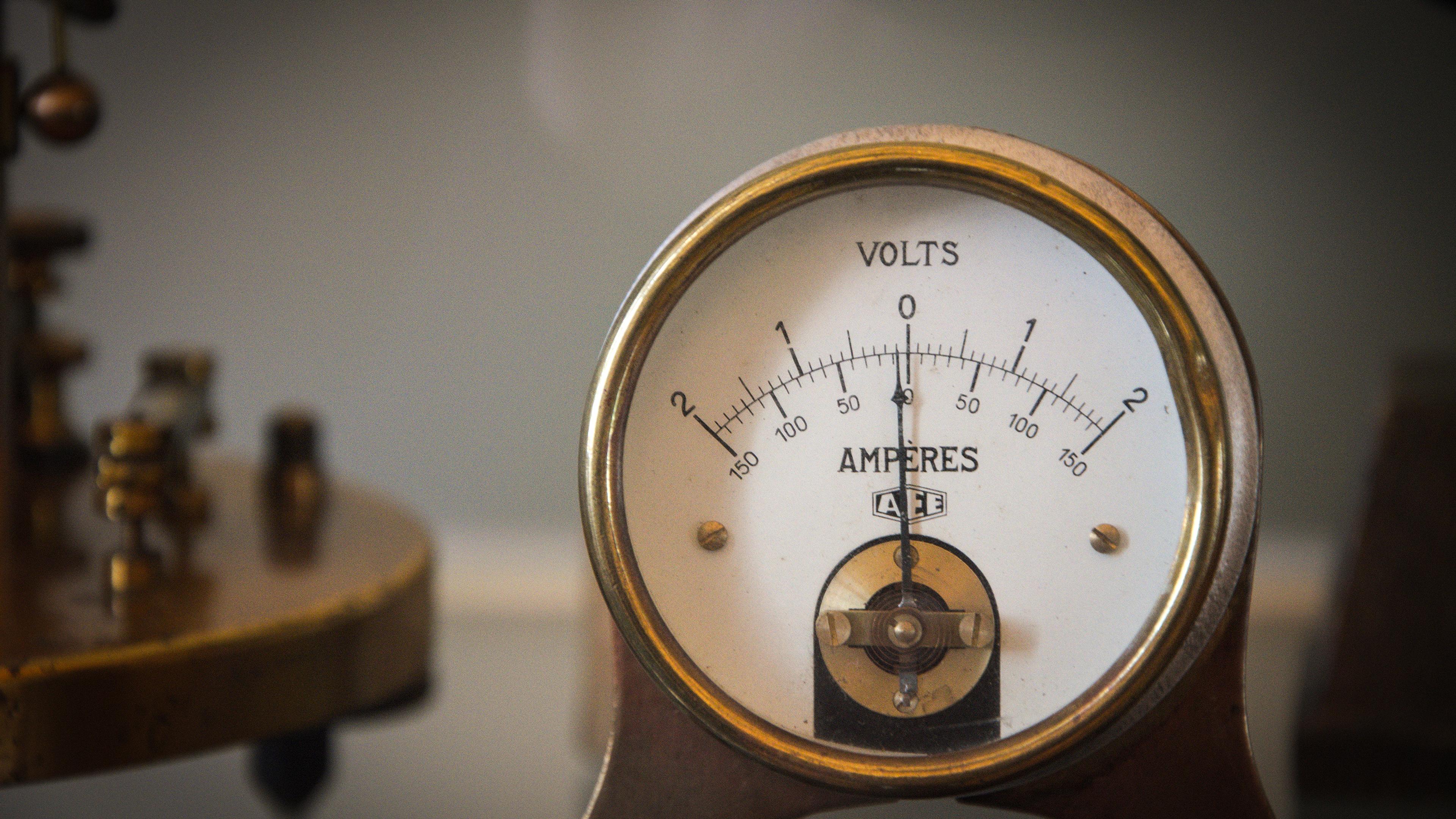

You enter a quiet laboratory room. Three people sit silently on chairs, electrodes attached to their wrists. An experimenter turns to you and explains the situation: two of these volunteers will receive a painful electric shock, while a third volunteer will be spared. That is, unless you choose to redirect the electricity to the third person instead. The choice is yours: act to ensure only one person receives the shock, sparing the majority, or do nothing and let two people experience the pain.

In this moment of decision, how confident are you about what you would do? Most of us like to think we know ourselves well enough to predict how we’d behave in moral situations. We imagine ourselves as making principled decisions based on clear ethical frameworks – such as never intentionally causing another harm, or doing what we can to reduce the overall amount of harm.

But research suggests that real-life moral decision-making is more complex than we typically assume. Our lives are filled with moral decisions that rarely come with clear guidelines – and the specific context can make all the difference.

Should you report a colleague’s misconduct? Yes, you might say. But what if it might cost them their job during an economic downturn? OK, then maybe no. But would your answer be different again if you knew they could easily find another position?

Or what about when a friend asks your opinion of their relationship troubles? Should you be completely honest? What if you think the truth might damage your friendship?

For decades, moral philosophers and psychologists have used hypothetical scenarios called ‘trolley problems’ to study how people make moral decisions. One basic version – first proposed by Philippa Foot in 1967 – involves deciding whether to pull a lever to save the lives of five people imperilled by a runaway trolley, by diverting the trolley towards a sixth person who was previously safe.

These thought experiments have captured the public imagination, spawning memes, appearing in TV shows such as the US series The Good Place, and becoming a staple of ethics classes and dinner party conversations. Their enduring appeal isn’t surprising. Trolley problems strip away the complexities of real-life moral decisions to focus on a single, sharp ethical choice: would you harm one person to save the many?

But these dilemmas have one crucial limitation: they’re hypothetical. When you’re reading about an imaginary trolley, the stakes feel abstract. No real person’s pain or suffering hangs in the balance. There’s a vast psychological distance between contemplating harm in theory and actually causing it – between imagining what we might do and discovering what we will do when our actions have real consequences.

They could walk up to a person, look them in the eyes, and press a button to say they should receive the pain

My colleagues and I wanted to find a way to bridge this gap between thought experiments and reality, so we designed a study that would preserve the ethical core of trolley problems while introducing genuine moral stakes. We couldn’t use actual trolleys, of course, but we could create a real-life moral dilemma that captured the essential ethical conflict of whether to deliberately harm one person to save multiple others.

We recruited hundreds of participants and first we asked them to respond to a series of traditional hypothetical dilemmas. This included a classic variant of the trolley dilemma as well as other imaginary scenarios, such as whether a military general should authorise bombing a terrorist hideout knowing it would also strike a nearby kindergarten.

Two weeks later, the same participants found themselves in our laboratory, facing an actual choice about administering electric shocks (safe but painful) to real-life volunteers. They could choose to do nothing and let two of the designated volunteers experience the pain, or they could walk up to the third person, look them in the eyes, and press a button on their shoulder to designate that they should receive the pain instead.

In a sense, when our participants were answering the hypothetical moral dilemmas, they were making predictions about their own morality, imagining how they would react when faced with similar real moral choices. By comparing their behaviour in the real-life lab situation with their hypothetical answers, we could see how much insight they had.

Our results were revealing. Although we found some connection between the participants’ hypothetical answers and their real-life choices, it was only very modest. In other words, even in this simplified moral context, carefully designed to mirror trolley problems, people’s moral philosophising provided only a rough sketch of their actual choices.

Some participants felt that experiencing pain in a group was less distressing than suffering alone

Perhaps this shouldn’t be too surprising. After all, when people face real-life moral dilemmas, additional moral shades and textures quickly emerge. One way we were able to show this to dramatic effect in the lab was by introducing a historical context to the decisions.

After participants made their initial choice about the electric shocks, we had them witness the consequences – they sat and watched as the volunteers received the shocks. Then we confronted them with the same moral problem as before: would they choose to harm the single person to save the pair?

Superficially, the ethical calculus was identical and yet something fundamental about the situation had changed. Now there was a history, a context in which the dilemma was embedded. Now some of the volunteers had already experienced pain, while the others had been spared. This seemingly small shift had a remarkable effect. Many participants, but not all, chose to reverse their original decision the second time around. In fact, the impact of prior events on participants’ decision-making was so powerful that knowing their first decision told us nothing about what they might choose the second time.

When we asked participants to explain their choices, their responses painted a richer picture than traditional philosophical frameworks would suggest. While some framed their decisions in terms of calculating overall harm (‘better one person suffers than two’) or a principled refusal to harm others (‘I won’t actively cause harm to anyone’), many provided alternative considerations. For instance, some participants felt that experiencing pain in a group was less distressing than suffering alone – ‘The single person was already unlucky to be sitting alone. The pair of people are with two, so they have each other,’ as one participant explained.

Other participants told us they were deeply concerned with fairness across time, wanting to ensure no one person or group bore too much of the burden: ‘I consciously decided to do the opposite of what I had done before,’ said one. Some participants struggled with the weight of responsibility itself, preferring to let fate take its course rather than actively choosing who would experience pain: ‘Fate has decided who was sitting where and I did not want to be responsible for who was the victim.’

These varied responses challenge the way moral philosophers typically think about trolley problems. Rather than simply applying deontological principles (eg, never do harm) or calculating utilitarian outcomes (eg, choose the option that lowers the overall burden of harm), our participants were acutely aware of the human context surrounding their choices – who had already suffered, who might suffer next, and how that suffering would be experienced.

We think this reveals a profound lesson about moral decision-making: our ethical choices do not exist in isolation, like mathematical equations waiting to be solved. They are more like notes in a piece of music, where harmony depends not just on the individual note but on what came before and what might follow. The same action – redirecting harm from two people to one – can feel intuitively right in one context and jarringly wrong in another, just as the same musical note might create either discord or resolution depending on its place in the melody. What changes isn’t the ethical mathematics of ‘one versus two’, but the context that gives those numbers meaning.

Moral decision-making, like music, is inherently relational

In real life, we rarely face dramatic trolley-style dilemmas, but we frequently encounter situations that echo these same moral complexities – for instance, choosing between the conflicting needs of friends, family and colleagues, or between practicalities and principles. These everyday decisions aren’t just about calculating harm versus benefit – they’re about navigating intricate webs of responsibility, fairness and human connection. Our research suggests we should be humble about our ability to predict our own ethical behaviour. The principles we hold in theory may shift when we face actual dilemmas.

This does not mean people’s moral philosophising is meaningless. What we think about moral principles does guide our actions. But it is just one element in a complex psychological equation that includes emotion, context and our sense of connection to others. Moral decision-making, like music, is inherently relational. We don’t judge a note in isolation, but by how it contributes to the larger melody. Similarly, we make moral choices not through abstract principles alone, but by considering how they resonate with the broader pattern of human experiences and consequences. For these reasons, morality is not easily captured in a fixed set of rules or decision algorithms. Each decision is both an ending and a beginning, a resolution and a prelude to what comes next.

Perhaps then, the path to making better moral decisions lies not in seeking absolute rules to live by, but in developing the wisdom to navigate uncertainty. In practice, this means recognising that moral situations rarely present themselves as cleanly as abstract problems do. It means understanding that what seems clearly right when we are contemplating hypothetical scenarios might feel very different when we are facing real people and real consequences. It means acknowledging that our past choices and relationships shape our future decisions in ways we might not anticipate.

By embracing the inherent complexity of moral choices, we might approach difficult decisions with more humility as we come to see that even our most firmly held principles can bend when confronted with the nuances of real life. In doing so, we might find ourselves not only more thoughtful about our own decisions, but more understanding of the intricate improvisations others make as they navigate their own ethical challenges.