Consider the circumstances of a 17th-century woman – albeit one of aristocratic roots – who wants to think and write about philosophy but faces a society-wide prejudice that women are just not cut out to think abstractly. Given the importance to philosophy of dialogue, criticism, debate and discussion with others, how can you develop your ideas in this context?

Something very like this was the situation facing Margaret Cavendish. Nevertheless, she found imaginative ways to have conversations with herself that helped her get around this exclusion on grounds of gender.

At the beginning of her Observations upon Experimental Philosophy (1666), Cavendish explains that ‘By Discourse, I do not mean speech, but an Arguing of the mind … for Discourse is as much as Reasoning with our selves’. Her point is that, when we are thinking through an issue, the reasoning process often takes the form of a back-and-forth. Objections, concerns or problems arise as we try to work through a point. Some will need to be addressed, others might be left aside, while some might be insurmountable. Sometimes, this can make it feel like there is someone there, inside your head, actually responding to you. No wonder, then, that many famous works of philosophy take the form of dialogues. Plato, Galileo, George Berkeley and David Hume all published works that present ideas to the reader as if emerging from a conversation between two (or more) interlocutors.

This sense of thinking through an issue as a back-and-forth is something that philosophy teachers (myself included) often try to encourage in students. I advise them to read their work and imagine someone (perhaps annoyingly child-like) asking Why? at every possible juncture. What’s the evidence for that? What argument supports that? What are the counterarguments? Those questions need to be acknowledged, if not always sufficiently answered. Further, although Cavendish herself suggests that ‘discourse’ need not involve speech, sometimes it can be helpful to vocalise issues as they arise. Again, I often encourage students to read their work aloud, or try to explain their ideas (elevator-pitch style) to peers or friends. As Daniel Dennett has noted, sometimes just ‘blurting things out’ can give you something more tangible to work with than the thoughts in your head.

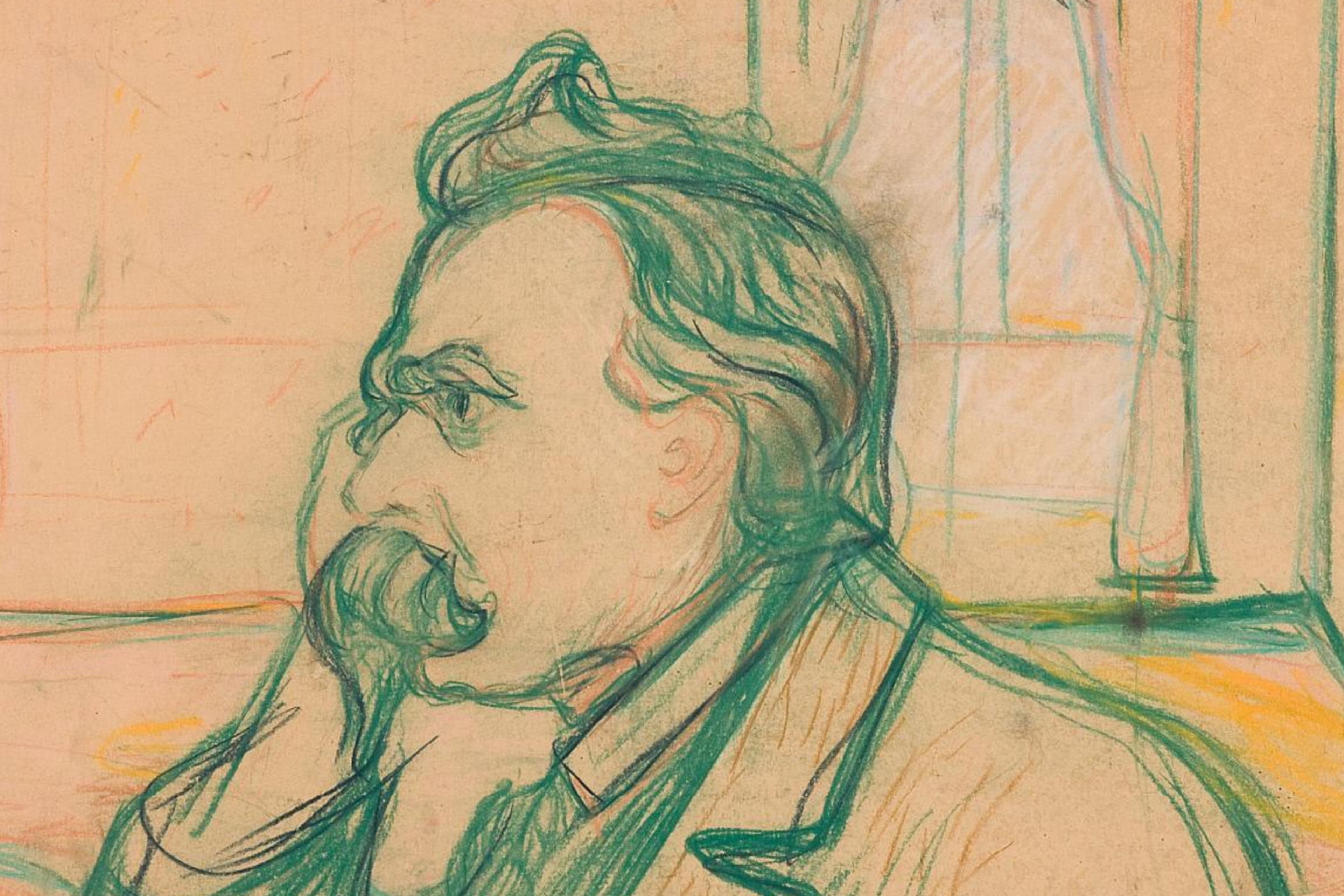

The idea that reasoning takes the form of dialogue between ideas and objections, problems and solutions, is not novel – it has been an aspect of philosophy from its earliest days. However, the way that Cavendish treats this process is unusual. Writing in the second half of the 17th century, Cavendish was the Duchess of Newcastle and spent the English Civil War in exile in France (where she met her husband, then just a marquess, later a duke). As scholarship in the past 20 years (especially the pioneering work of the late Eileen O’Neill) has shown, and despite the impression that traditional surveys of the period give, the 17th century was not entirely devoid of women philosophers. Women published on topics in political, moral and ‘speculative’ philosophy (ie, metaphysics). Nonetheless, Cavendish was writing at a time when the prevailing view was that only men were cut out for a life of reflection, while women were better suited to more menial affairs. Even a century later, Immanuel Kant would remark, in response to the work of Emilie du Châtelet (an early philosopher of science) that she ‘might as well have a beard’. His point was that, in producing excellent scholarship, du Châtelet wasn’t doing what was expected of a woman. She was behaving like a man.

Cavendish was well aware of the social restraints on her philosophical endeavours. In the preface to the Observations, she notes that her male peers ‘will perhaps think me an inconsiderable opposite, because I am not of their Sex’. Similarly, in her Philosophical Letters, she writes: ‘I have been informed, that if I should be answered in my Writings, it would be done rather under the name and cover of a Woman, [than] of a Man, the reason is, because no man dare or will set his name to the contradiction of a Lady …’

The evidence suggests that her concerns were borne out. Although she was able to garner some engagement from her peers, much of it was trivial – often praising her achievement in publishing philosophical texts despite being a woman. What’s more, there is no evidence that the most prominent philosophers of her day, such as René Descartes or Thomas Hobbes, whose views are the direct targets of many of her own arguments, took any notice of her at all. As any practising philosopher will know, feedback is crucial to the development of ideas. Even disagreement is useful in identifying where the problems with one’s ideas might lie, and what can be done to address them. But Cavendish was not able to benefit from peer review; she did not engage in any correspondence with other prominent philosophers, and her ideas received no substantial criticism.

In lieu of engagement from her peers, Cavendish took matters into her own hands. In her philosophical writings, one finds her claim that ‘Discourse is … Reasoning with our selves’ interpreted with great imaginative wit. I want to point out three ways that she put the tool of talking to oneself to work.

When Cavendish’s Philosophical Letters (1664) were published, epistolary writings, in which prominent figures debated the most significant philosophical issues of the day, were common. For this reason, the 17th-century intellectual scene was dubbed ‘The Republic of Letters’. In her own Letters, Cavendish critically responds to the work of four well-known ‘natural philosophers’: Descartes, Hobbes, Henry More and Jan Baptista van Helmont. However, the letters themselves are all addressed to an interlocutor simply referred to as ‘Madam’. It is hard not to think that Cavendish is making a point here: Since no one will respond to me, I’ll have to do it myself. As she puts in the preface to the Letters, ‘I have done that, which I would have done unto me …’ However, further remarks indicate that, beyond making a point, Cavendish also recognised the value of this form of self-critical writing. She continues: ‘I am as willing to have my opinions contradicted, as I do contradict others, for I love Reason so well, that whosoever can bring most rational and probable arguments, shall have my vote …’

There is, then, a benefit to having one’s ideas challenged. The aim of reasoning in philosophy is not to defend a particular piece of intellectual territory, but to get closer to truth. Having one’s commitments and assumptions pointed out, and noting how they influence one’s way of thinking, is an important step towards this. As Susan Stebbing would later put it, we must find a way to challenge our most ‘cherished beliefs’. The alternative is to spout dogma or to cling ignorantly to unjustified views.

The second example is from the Observations; specifically, a section titled ‘An Argumental Discourse’. We have already seen that Cavendish takes ‘discourse’ to involve ‘reasoning with ourselves’. Here that claim is interpreted literally. The section begins:

When I was setting forth this Book of Experimental Observations, a Dispute chanced to arise between the rational Parts of my Mind concerning some chief Points and Principles in Natural Philosophy; for, some New Thoughts endeavouring to oppose and call in question the Truth of my former Conceptions, caused a war in my mind …

Cavendish presents herself as literally in two minds. The two ‘parts’ of Cavendish’s mind cannot come to an agreement (perhaps reflecting the fact that reasoning can sometimes lead to an impasse). She thus asks her readers to play the role of an impartial judge and ‘if possible, to reduce them to a set[t]led peace and agreement.’ Again – as I have often told my students – sometimes you need to speak to someone else before you can work out what you really think. Undoubtedly, part of Cavendish’s aim here is to describe, albeit in an exaggerated fashion, her own reasoning processes. But I also think we can read the ‘Argumental Discourse’ as a deconstruction of the dialogue form. Why did Plato write Socratic dialogues? Perhaps in part because that is how he arrived at his own conclusions and how he hoped his readers would too – even if they didn’t agree with him.

The final example is from The Blazing World, a short novel by Cavendish, published alongside the Observations. The novel is high fantasy: the protagonist, known only as ‘the Empress’, sails through a portal at the North Pole that takes her into another world. The woman becomes the Empress of this new world, which is inhabited by anthropomorphic animals: bear-men, bird-men and worm-men among them. Having reorganised this world into a utopian society, the Empress decides to write philosophy. She asks the immaterial spirits that inhabit this world to summon a great thinker to assist her. First, she calls for Galileo, Descartes or Hobbes, among others. However, she is informed that while these men are ‘fine ingenious Writers’ they are also ‘so self-conceited, that they would scorn to be Scribes to a Woman.’ So, instead, the Empress summons a woman: the Duchess of Newcastle – that is, Margaret Cavendish herself!

The Duchess and the Empress form a close relationship, seeking counsel in one another, engaging in shared intellectual pursuits, and even becoming ‘Platonick Lovers, although they were both Femals’ [sic]. Indeed, in one of the most ambitious parts of the novel, the souls of the Duchess and the Empress inhabit the mind of the Duke of Newcastle (Cavendish’s husband), and the three of them then enjoy a (spiritual) polyamorous relationship.

This example of Cavendish talking to herself through her writing introduces a new element not there in the previous examples. Here, rather than just ‘discoursing’ towards a particular conclusion, Cavendish seems to be advocating forming a relationship with oneself. This includes more than just being able to think through an issue, and promises to lead to something akin to spiritual contentment. Perhaps she was on to something. At the very least, her highly imaginative responses to intellectual isolation should be acknowledged, celebrated and, I think, learnt from.