Felipe De Brigard, a memory researcher and philosopher at Duke University in North Carolina, has a problem with the expression ‘forgive and forget’. The pairing goes back centuries. ‘You must bear with me. Pray you now, forget and forgive,’ Shakespeare’s King Lear tells Cordelia. ‘Let us forget and forgive injuries,’ Cervantes wrote in Don Quixote. To advise someone to ‘forgive and forget’ suggests that forgiving must go together with forgetting, or allowing a past wrong to escape one’s mind.

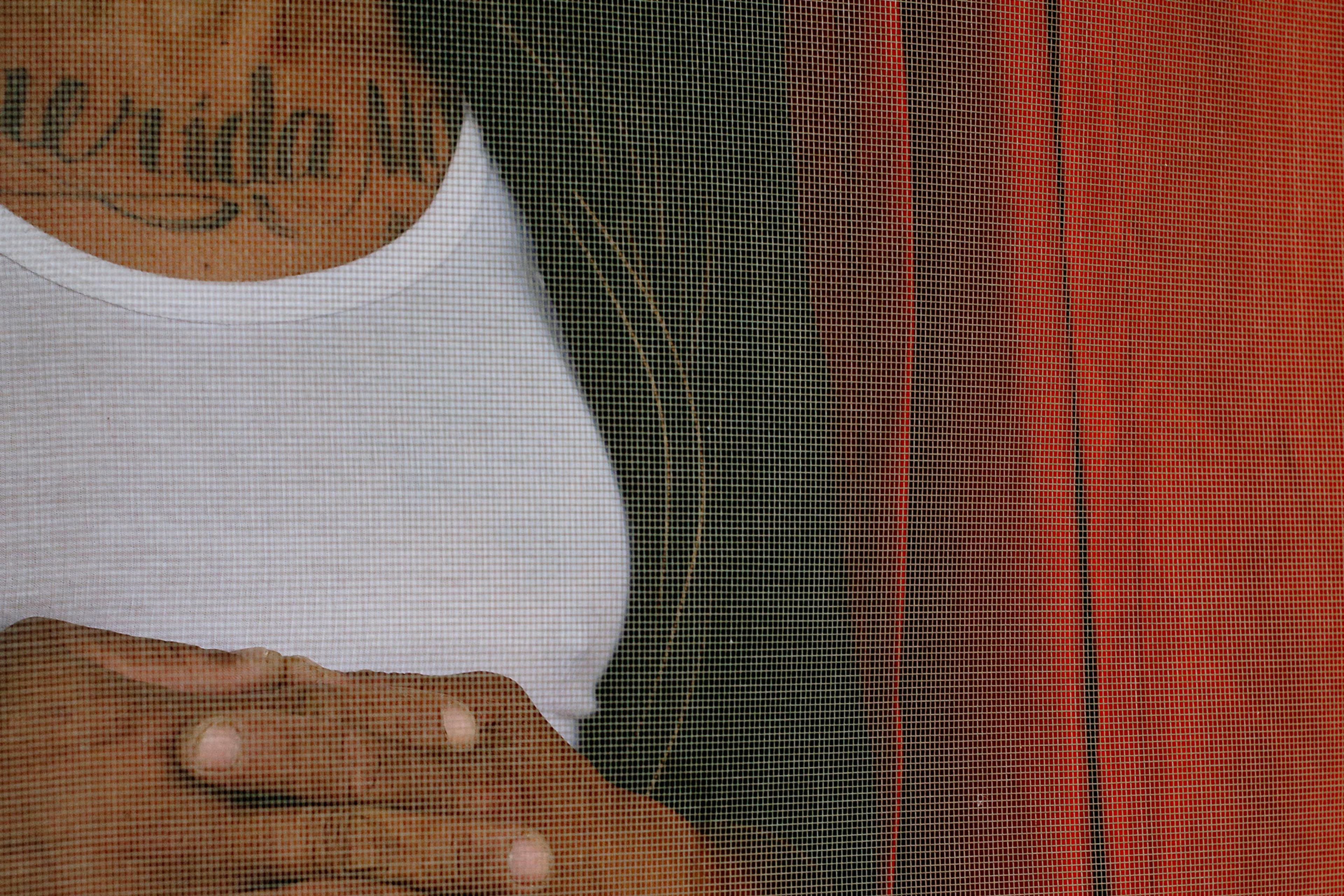

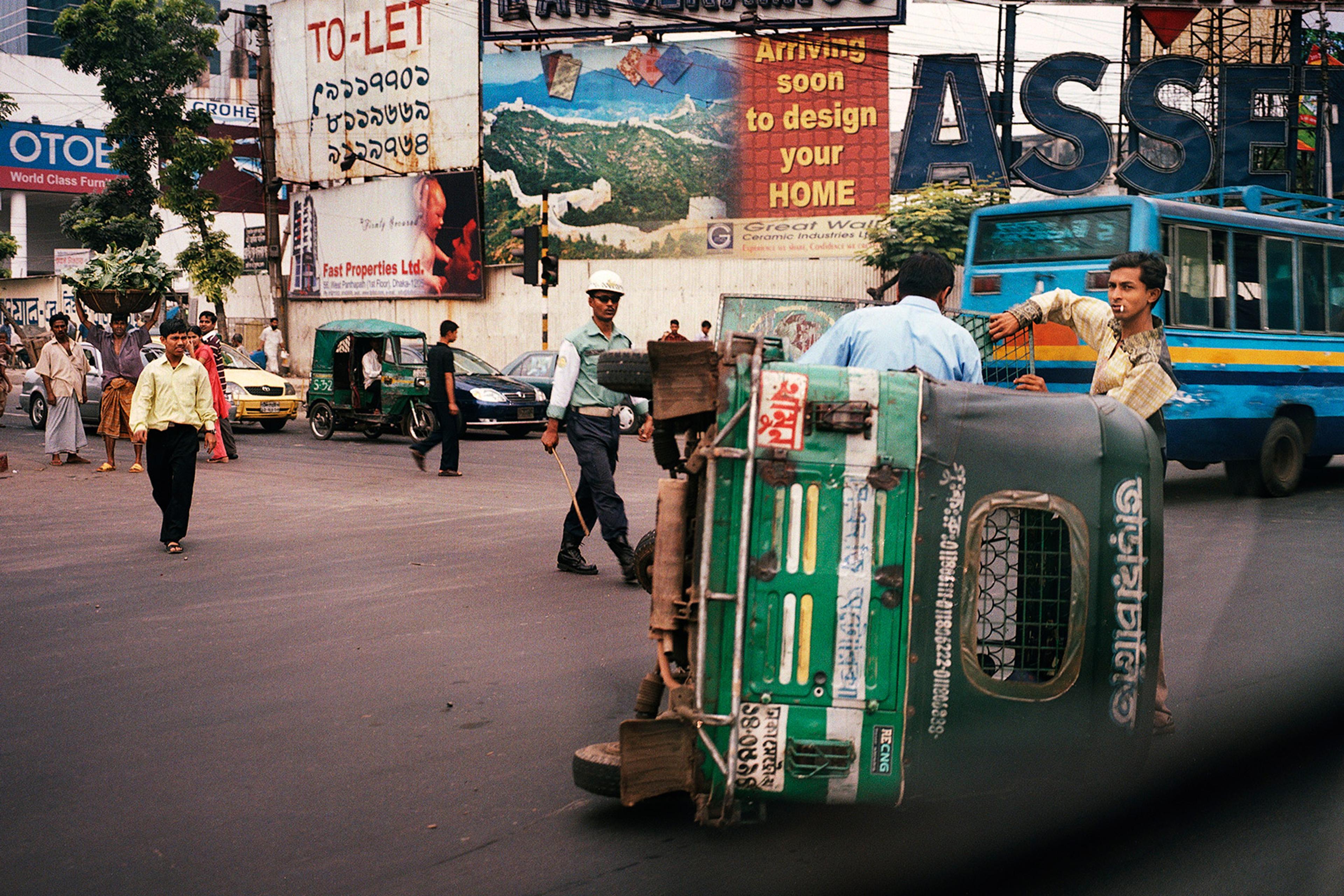

Yet, De Brigard grew up in Colombia, where he, and many others, have memories of wrongdoing that are difficult to forget. The South American country was in a state of war for more than 50 years, which killed at least 220,000 people; it’s estimated that 80 per cent were civilians. De Brigard was a child in the 1980s in Bogotá. His family members and friends were besieged by the activities of drug cartels and the war among the army, guerrillas and paramilitaries. ‘Bombings were common,’ he says. ‘We all knew people that had gotten killed or wounded in such events.’ From 1996 to 2005, someone was reportedly kidnapped every eight hours. ‘Parents of many school-friends were kidnapped, some never to come back,’ De Brigard recalls. ‘My childhood friend had to flee Colombia unexpectedly, as she narrowly survived a kidnapping attempt. I never got to say goodbye.’

When a peace deal was ratified in 2016 and The Guardian asked Colombians for their thoughts, several mentioned the need for forgiveness. ‘It is with inclusion and forgiveness that we become a better country,’ said one 23-year-old. Forgiveness can be difficult under any circumstances, and if forgetting is a key part of it, that might make it even harder in contexts such as this one.

Last year, De Brigard received a grant to uncover what the relationship really is between forgiveness and memory. When people forgive, is it because their memories of past wrongs have faded? This would mean that unforgiven events are likely to be remembered with more clarity and detail, while wrongs that people have forgiven are less vividly recalled, if they are remembered at all.

De Brigard endorses a different explanation: that forgiveness is closer to emotional reappraisal. Emotional reappraisal involves reframing the meaning of something that’s happened in order to change its emotional impact. In everyday life, this might involve thinking about a challenging experience from a new perspective that leads to less anger, anxiety or sadness. It changes the emotions a person feels about an event, but not the details of the event in one’s memory. He considers it to be ‘memory mollification’ rather than a ‘memory modification’. When a memory is mollified, ‘[you] may still remember the event as it actually happened but, when you do, you don’t experience it as negatively as you did before or with as much intensity,’ De Brigard says.

If forgiveness is similar to reappraisal in this way, then forgetting isn’t necessary: the memory of an event doesn’t have to get weaker for someone to forgive. If that’s the case, we can expect that ‘both people that have forgiven and people that have not forgiven experience their memories with equal clarity,’ De Brigard says.

To explore whether that is true, De Brigard conducted an initial set of experiments with online participants. He and his colleagues asked people to recall an event from within the past 10 years in which someone else harmed them emotionally or physically. Some were asked to think about a time when they forgave the perpetrator; others recalled an event that they had not forgiven. Then, the participants filled out a questionnaire assessing how well they remembered the details of the event, such as the sensations they experienced at the time. The two groups – those who had forgiven and those who hadn’t – showed no differences in how well they said they remembered the details of the events.

What did change: the ones who said that they had forgiven the perpetrator rated the intensity of their emotions lower as they recalled the event, and indicated that the wrongdoing wasn’t as important to their current lives or as central to their identity. People who recalled something they had forgiven also had a lower desire for revenge over it and less of a need to avoid their perpetrators. ‘What they have done is that they have reappraised the affective components of their memories,’ De Brigard says. ‘When they remember it, they still remember the events that happened,’ but less negatively.

De Brigard will now take similar experiments to Colombia: to those who survived violence in Montes de María, in the north of the country, and to people in Bogotá who were not directly affected but knew others who were, as well as a comparison group in the United States. Some of the areas of Colombia where the team will be conducting their interviews are in parts of the country he never dreamed of going to when he was growing up. ‘The project is in very rural areas in Colombia that were particularly affected by the violence,’ De Brigard says. ‘They experienced awful things: people killed in front of them, kidnappings, disappearances. Almost all of them had to be displaced and leave everything behind.’

He believes the team’s work will continue to reveal the connection – or lack thereof – between a diminishment of memory and forgiveness, and how forgiveness involves changing the emotional aspects of a person’s experiences. What they find could also help people who are struggling with forgiveness.

Even without forgiveness, someone may still be able to feel relief with emotional reappraisal strategies

‘There are people that want to forgive, and [do] bring themselves to forgive,’ De Brigard says. ‘And there are people that don’t want to forgive, and they can’t bring themselves to forgive. You cannot force them to forgive.’ There’s also a third group: those who want to forgive but can’t. ‘What people are seeking is solace that people who have forgiven have achieved,’ De Brigard says.

If forgiveness typically involves emotionally reappraising what has happened, then it might be possible to reach that same solace without having to forgive. Here’s how his theory allows for this: even without forgiveness, someone may still be able to feel the relief that forgiveness provides if they’re taught emotional reappraisal strategies for the negative feelings that arise when they think of the wrongdoing. The end result could be close to forgiveness. One example of such an approach could be temporal distancing. This is a reappraisal strategy that prompts people to imagine how they might feel about an event in the future (eg, less intensely), which research suggests can reduce negative feelings in the present.

‘I think there are offences that are unforgivable, and that we don’t have a moral obligation to forgive them,’ De Brigard says. ‘Nevertheless, the psychological effects of forgiveness might be sought after.’ With other reappraisal strategies, some people who can neither forget nor forgive what has happened to them may still be able to find their way toward peace.

This Idea was made possible through the support of a grant to Aeon+Psyche from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. Funders to Aeon+Psyche are not involved in editorial decision-making.