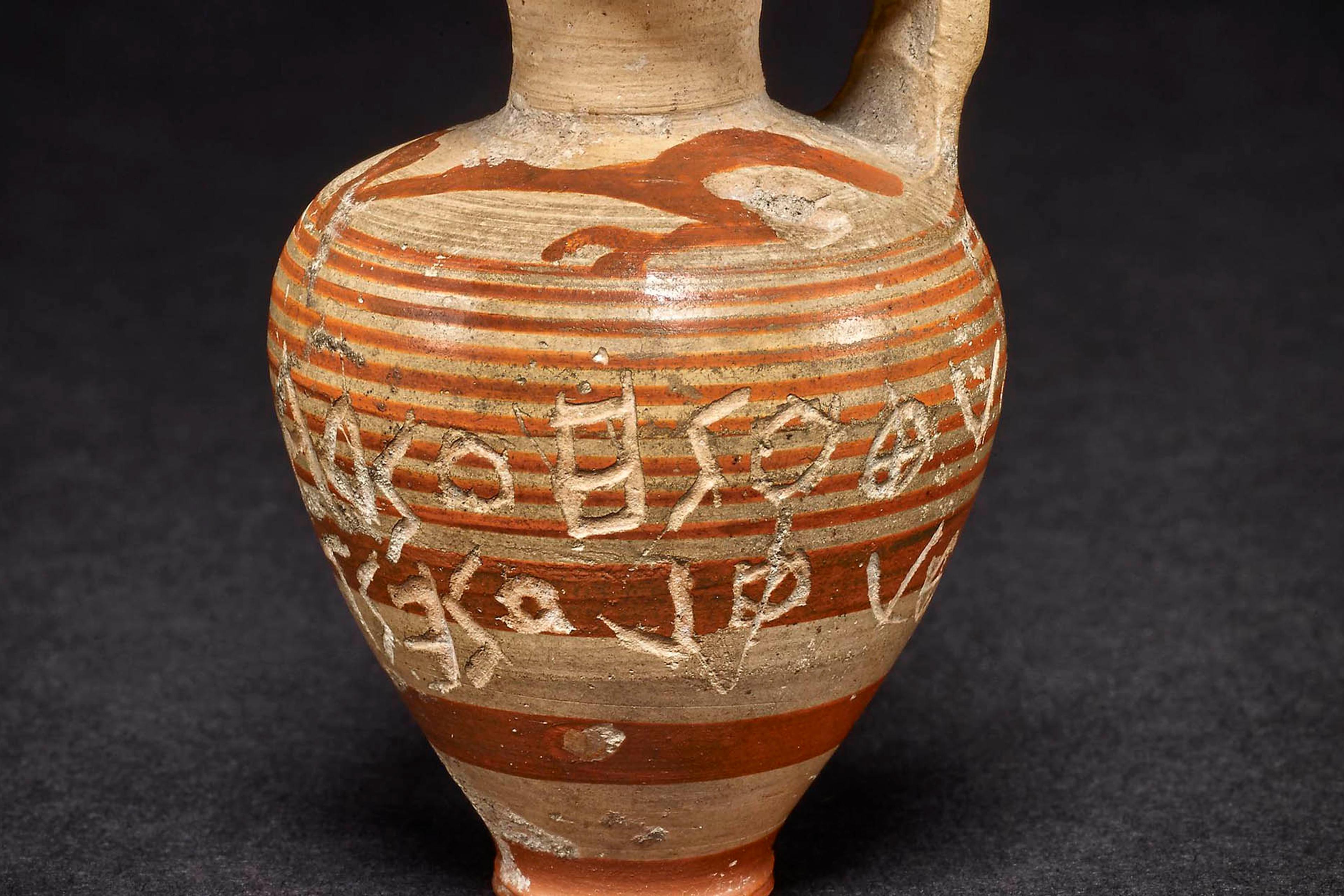

On 8 December 1869, the Austrian author Leopold von Sacher-Masoch signed a ‘love contract’ with his fellow writer Fanny Pistor. The terms were straightforward. He submitted himself to her as a ‘slave’ for six months, while she took on as many other lovers as she pleased. She agreed not to ‘demand anything disreputable of him – anything that would make him disreputable as a human being and a citizen’ and to allow him six hours a day to write. Furthermore, ‘the subject shall obey his sovereign with complete servility and shall greet any benevolence on her part as a precious gift.’ In exchange for Sacher-Masoch’s ‘slavish submission’, his mistress promised to wear furs as often as possible.

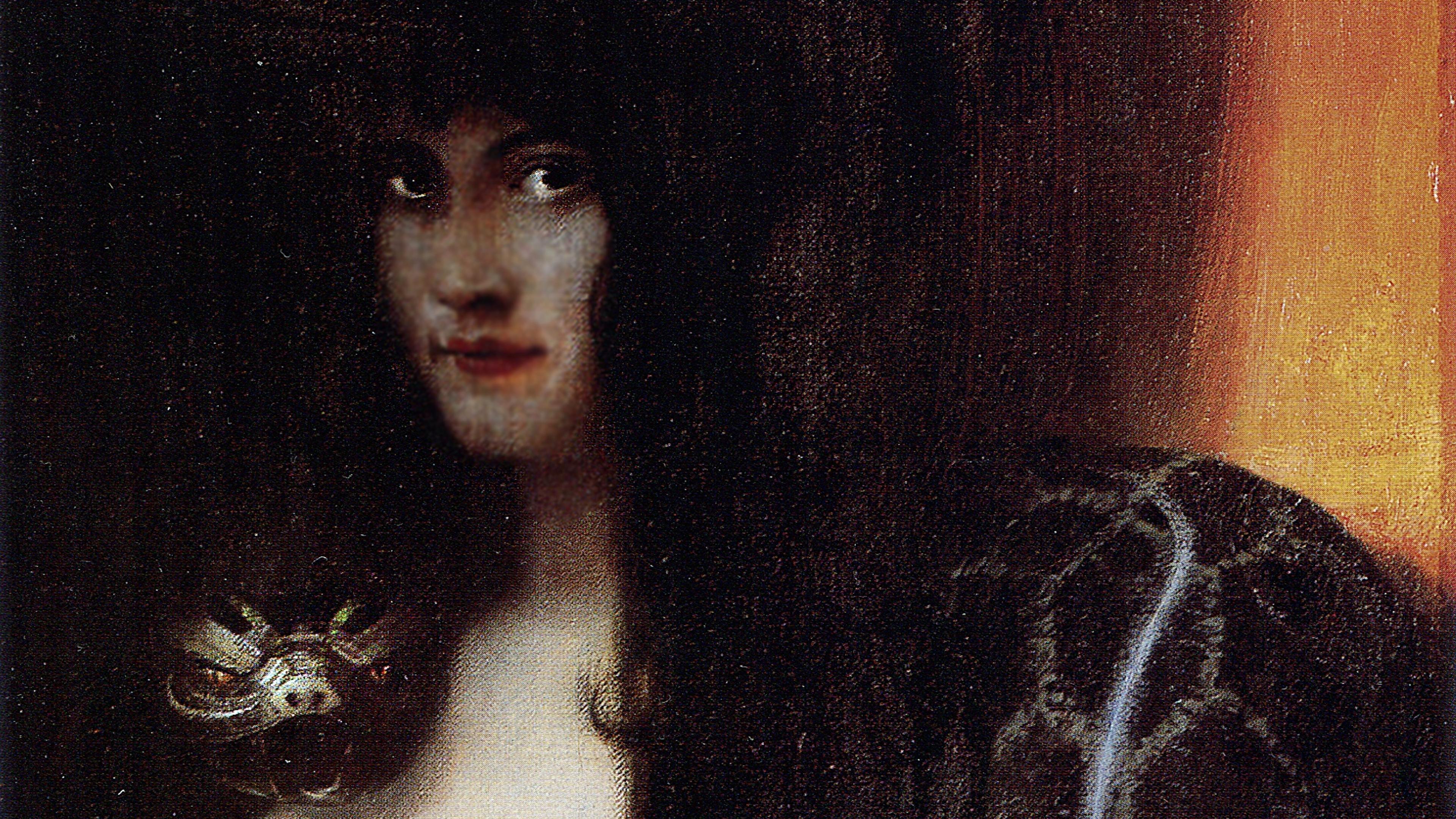

The affair inspired Sacher-Masoch’s most notable work, a Darwinian novella called Venus in Furs (1870). It is about a similar arrangement between Severin von Kusiemski and Wanda von Dunajew – only Severin signed on as Wanda’s ‘absolute property’, giving her the right to kill him. The popularity of the book led the German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing to coin ‘masochism’ after the author (without his approval and much to his disdain) in his medico-legal study of sexual pathology, Psychopathia Sexualis (1886): ‘a peculiar perversion … in which the individual affected, in sexual feeling and thought, is controlled by the idea of being completely and unconditionally subject to the will of a person of the opposite sex; of being treated by this person as by a master – humiliated and abused.’

For Sacher-Masoch, supersensuality – the longing for cruelty over intimacy – was a symptom of ‘unnatural’ modern love. His works are an exploration of these ‘dark sides’ of love, while Krafft-Ebing interpreted them as material for pathological investigation. An opponent of marriage, Sacher-Masoch argued in his cycle of novellas Die Liebe (1870) that male submission was a sensual escape from the pressures of being a sole provider, that female infidelity was a consequence of women’s exclusion from work, and that only when a man sees a woman as an intellectual equal are they able to achieve matrimonial bliss. It reveals that the foundation of female dominance in BDSM (erotic practices including bondage, discipline and sadomasochism) is not female empowerment but men’s surrender to unrecognised female potential.

As a female dominant (femdom) in the 21st-century fetish sphere, I still deal with the same gendered themes. Masculine subjectivity has evolved, mostly in the ways in which women can cater to it: there is an enormous variety of female domination today. There’s the domme who takes a more dominant role in the relationship, sometimes unwittingly. She may engage in pegging, or the anal penetration of her male partner using a strap-on dildo. Then there are the extreme dynamics that typically don’t involve sexual intercourse: the findomme who practises financial domination (findom) by letting men spoil her with gifts or ‘tributes’ for her attention; the dominatrix who charges for professional masochistic experiences, like physical or emotional degradation and humiliation; and the mistress, who typically ‘owns’ a domestic ‘slave’.

I’m more of a hedonistic domme, like the character Venus who appears at the beginning of Venus in Furs, taunting the unnamed narrator with the feminine advantage: ‘Man desires, woman is desired.’ In Masochism: Coldness and Cruelty (1967), Gilles Deleuze referred to this archetype in Sacher-Masoch’s work as Aphrodite:

Her life … is dedicated to love and beauty; she lives for the moment. She is sensual; she loves whoever attracts her and gives herself accordingly. She believes in the independence of woman and in the fleeting nature of love; for her the sexes are equal …

But it’s not that aesthetic freedom that attracts my submissives. It is my coldness, my promiscuity, and my disregard of men outside their erotic purpose. In saying that, my perspective is not that of a sadist. I do not have violent sentiments against men. If I’m cruel, it is only because my ways attack their unresolved beliefs of what a woman should be. This, as Deleuze noted, makes me ‘the woman torturer of masochism [who] cannot be sadistic precisely because she is in the masochistic situation, she is … a realisation of the masochistic fantasy.’

In 1889, Sigmund Freud popularised the concept of sadomasochism (now known as S&M), which positioned masochism as a feminine counterpart of sadism – a term Krafft-Ebing coined based on Marquis de Sade’s sex crimes. Since then, we’ve adopted the misnomer of calling a masochist’s torturer a sadist, and a sadist’s victim – a masochist. In Sade’s novel Justine, or the Misfortunes of Virtue (1791), one of the monk’s victims states: ‘They wish to be certain their crimes cost tears; they would send away any girl who was to come here voluntarily.’ As a willing servant, a masochist is of no interest to a sadist.

The distinction, albeit overlooked, exists even in BDSM where consent is required and masochism has been far removed from its supersensual roots. In female domination, the man selects a woman he will make his goddess, like the male dominant who targets and grooms his prey. While the latter is not necessarily sadistic, the fantasy in both male dominance and sadism is the objectification of women, as exhibited in Sade’s literature. In Sacher-Masoch’s tales, however, the female abuser is glorified. Regarding what that makes of the dominant woman, Deleuze comments: ‘Whenever the type of the woman torturer is observed in the masochistic setting, it becomes obvious that she is neither a genuine sadist nor a pseudosadist but something quite different.’ [My italics.]

This became clear to me when one of my submissives left his girlfriend for me, a few months ago. I had met him only once, for which my time was compensated. ‘I would never ask you or anyone to do this for me,’ I remember saying, mindless that unappreciation aroused him. The gesture itself was not surprising. But the reason behind it was. When I asked why he suddenly wanted to ‘serve’ me, he said: ‘I see a beautiful, intelligent, powerful woman [who is] younger than me yet … able to tame me so easily.’ Our meeting was vanilla. It didn’t even involve the customary whipping, verbal degradation or any physical female domination, aside from him kissing my feet.

After that, I never talked to him again until he informed me about his breakup. He had simply eroticised my indifference like Sacher-Masoch’s supersensualist who voluntarily succumbs to the sternness of nature. Although I’m sure my sub sees it as a power play, female domination has never been a source of empowerment for me. To me, being a dominatrix has always been about providing a safe space for men to unburden themselves and be vulnerable. That is what’s quite different about what I do. If anything, I feel more like a distant mother to my clients.

This reminds me of the Darwinian theme of Venus in Furs – man’s struggle with his recreational needs and achieving a more equal dynamic between the sexes. It positioned men as a casualty of modernity, especially in this digital age when intimacy is as elusive as ever. The problem, like what Sacher-Masoch’s first wife Angelika Aurora Rümelin emphasised in her memoir, The Confessions of Wanda von Sacher-Masoch (1906), is that the supposed female empowerment that comes with a supersensual husband didn’t give her the privilege of self-representation. She was placed on a pedestal as a fantasy, not as a woman who truly had equal or more social power than her man.

Despite defending her husband when he was accused of suffering from a sexual anomaly, Rümelin felt trapped by the ‘occult power’ he held, the ‘“false” representation of female life in male art,’ as the historian Katharina Gerstenberger has said of Confessions. Sacher-Masoch’s masochistic tales failed to address the impact this power had on marriage and women’s social life. Rümelin, who had three children with Sacher-Masoch, thought that ‘male sexuality [is] an unpredictable force that even the institution of marriage cannot always successfully contain,’ as Gerstenberger put it.

After agreeing to cuck her husband per his submissive wishes, Rümelin later discovered that he had cheated on her. ‘I never saw Sacher-Masoch again,’ she said after learning that ‘there was a woman,’ as the maid informed her. She lamented how even the sanctity of marriage doesn’t secure her gendered roles as a wife and a mother: when a man betrays his wife due to complex sexual needs, she becomes an outcast of society and her own person, just as she was as a maiden.

Meanwhile, Sacher-Masoch revelled in his wife’s ‘honest’ infidelity and even prostituted her via newspaper ads. ‘How delightful to find in one’s own respectable, honest and good wife a voluptuousness that must usually be sought among women of easy virtue,’ he said. Masochists have a special attraction to female sexual freedom. As an open domme, I receive a lot of these cuckolding or ‘seeking: hot wife who will…’ offers. But as with Sacher-Masoch’s marital integration of his kinks, they are presented like requirements. My sexual decadence has always been individual – going after who I want, when and where I want it. It is not at all akin to when men dictate the scenes in which I get to be ‘free’ with another lover, especially when it always has to include them, as a voyeur or an active participant. A non-masochistic man doesn’t feel the need to be part of a woman’s sex life or what it symbolises; he simply desires her.

Supersensuality in the 21st century isn’t that different from its sources in the 19th century. Only, now, the lucrative demand for women in the sex and fetish industry has given us better self-representation and autonomy. In some capacity, there is more ‘shared work’, which Sacher-Masoch believed was key to a healthy bond between men and women. And with intimacy in trade, nature, as Sacher-Masoch claimed, is as cold as ever.

In Venus in Furs, Wanda ends up finding a lover in the dominant Greek aristocrat Alexis Papadopolis, who goes on to join her in punishing Severin. Although he recalls ‘dying of shame and despair’ during that moment, facing his ‘successful rival’, Severin initially ‘felt a kind of fantastic, supersensual fascination’ that soon brought the ‘dreadful clarity [of] how blind lust and passion have led men’ since the beginning of time. Reflecting on the experiment while talking to the unnamed narrator, Severin says: ‘The therapy was cruel but radical. The main thing is: I am healed.’ In a comical, misogynistic conclusion, he shares the lesson: ‘if only [he] had whipped her’, he wouldn’t have been a slave to his desires.

Severin explains that it’s women’s lack of equal opportunities that keeps them an enemy of men. From what I’ve seen in the journey of my supersensualists, as well as my masochistic admirers and lovers who inevitably measure themselves against my regular ‘stud’, it’s the increasing female independence that discharges the opposite sex from their traditional duties – a long-engrained purpose – that keeps men at the mercy of women.