When I first moved to the mountain, the mountain men – the Mountain Posse, as this self-styled renegade group called themselves – placed bets on how long I, a 28-year-old single woman from the suburbs, would last. The longest bet, so I’ve been told, was two years – one year to experience the brutal weather, and the second year to put my cabin on the market. Twenty-eight years later, the Mountain Posse has disbanded, and I’m still solo on the mountain.

In the abstract, the setting is idyllic: an isolated mountain cabin at the end of an abandoned logging trail in the Rampart Range in Colorado. The nearest county-maintained road is 2.6 miles distant at the base of the mountain, as is the community mailhouse and parking area. I split logs for the wood stove, hike the mountain trails daily (with 1.2 million acres, there are many trails to explore), wake to magnificent sunrises. I’m the second-longest tenured resident on the mountain and the only long-term, full-time single person. It’s a challenging life alone in this environment. Yet this very experience of solitude within a vast natural landscape is the reason I’ve stayed.

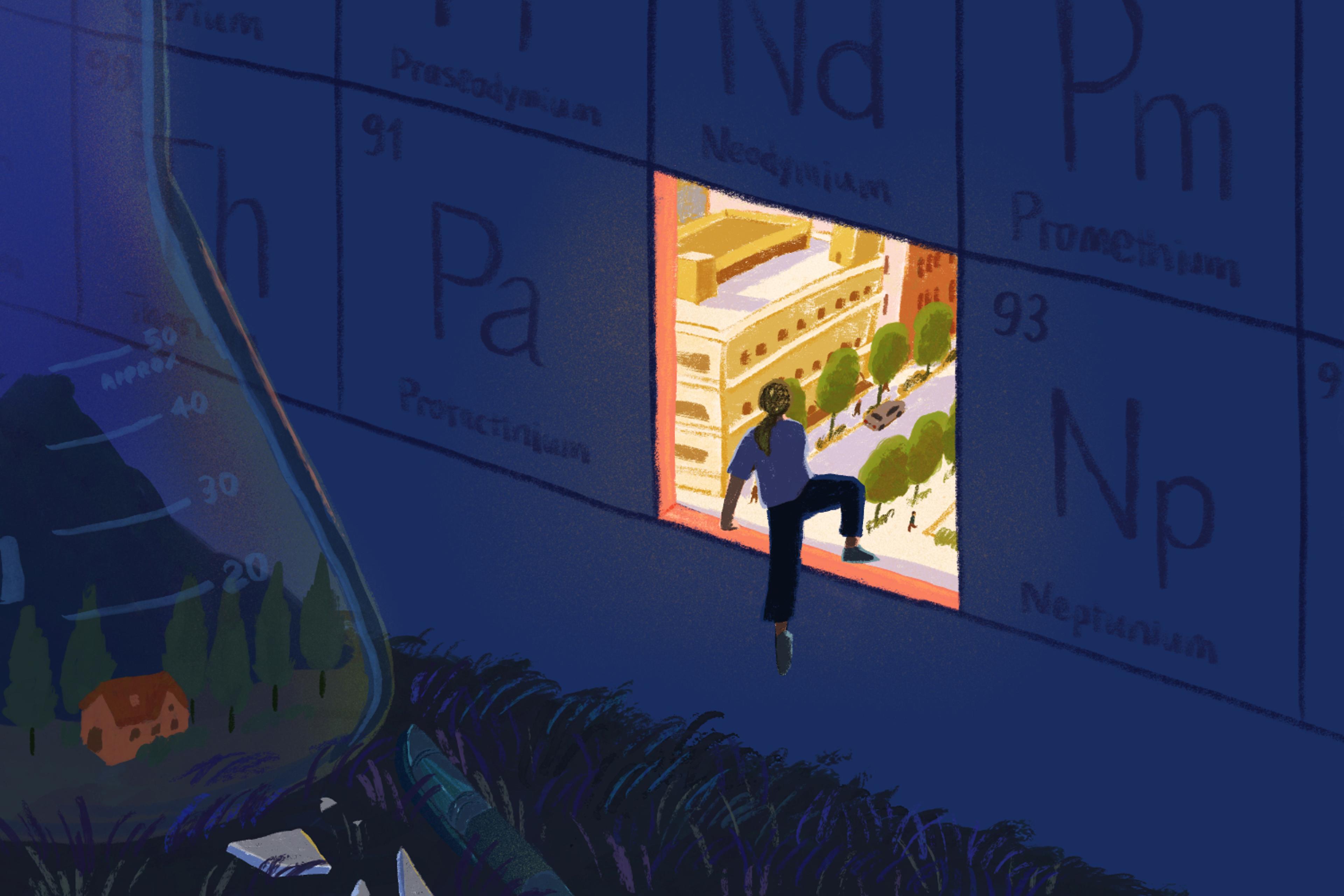

I don’t identify as a hermit or a recluse. Although I find spiritual fulfilment on the mountain, my solitude is not the result of a religious calling. Importantly, I didn’t move to the mountain with the goal of being alone. I moved here because the cabin was an affordable place to live while I fulfilled a four-year teaching assignment at a university 20 miles away. The resulting solitude was an unexpected discovery, then an unexpected benefit. At the end of those four years, I left my career and a brief marriage because mountain life was even more appealing than either of those.

I sleep in a hammock under the stars and take naps on the overlook

Nor is my solitude experimental. There is an abundance of personal narratives by men and women who have ventured alone into an isolated or semi-isolated setting for a specific purpose, for a specific period of time – Alice Koller’s An Unknown Woman (1981) and Alix Kates Shulman’s Drinking the Rain (1995) come to mind. In the main, their experiences are planned retreats from the trappings of the modern world, not permanent life changes. Even Anne LaBastille, the American ecologist and author of the Woodswoman (1976-2003) series, eventually became only a seasonal Adirondack resident. The more committed solitaries, such as the poet and novelist May Sarton, live in or near an established residential area. But to endure the solitude in a semi-wilderness setting, across decades, requires a different level of commitment.

In her Aeon essay on female hermits, Rhian Sasseen posed the question: ‘A woman alone, unwatched, unchaperoned and without children is impossible for us to process. What does she do with her time?’ I’ll tell you what I do with my time. On the mountain, I live simply. I read books. I cook all my meals – unadorned recipes, from basic ingredients, that freeze well. I take long, often meandering hikes into the woods. I write in my journal. I sleep in a hammock under the stars and take naps on the overlook. I bake bread from scratch. I rediscovered the simple pleasures of sewing. With only myself to answer to, I bought a piano (an overwhelming purchase at the time) and taught myself music.

Far from the madding crowd: the author’s house in winter. Photo courtesy Susanne Sener

Mostly I am still, basking in the absolute silence, unobserved by others, answering only to the mountain and to myself. The freedom is absolute, and it is exquisite. But here’s the rub: this kind of long-term contemplative solitude in a challenging environment demands logistical support. I choose to have electricity, running water powered by a well pump, propane gas, a reliable well-maintained vehicle, high-quality winter clothing and gear, and a stocked pantry and freezer chest. I choose not to rely on the mountain community for help (although occasionally I pay a neighbour to perform odd jobs I lack the skill sets to perform safely myself). Because I value my time enjoying this natural world rather than surviving in it (translation: I don’t hunt or forage for food) – and without a partner or patron, trust fund or other means of passive income – I must actively work to sustain my long-term solitude. For me that means a job in the city, an hour’s drive from the mountain. I find this weekday commute increasingly difficult to endure, both as a waste of my precious time and as a separation from the solitary life I cherish. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has enabled the company’s staff to work from home, at least for the near future. I know, though, that this respite is only temporary; one day I’ll have to return to the commuting life. But it’s a task I’ll willingly undertake to support this life path I’m travelling alone.

There are many benefits to a solitary life in nature: there’s the psychological peace that comes with living an unobserved life, but there are also physical advantages. I no longer attribute my physical health to good luck or good genes. Well into my 50s, I’m as physically active as I was in my 20s. I take no medications, my weight is less than what it was in college. I have suffered no major illnesses, only very minor colds, and no hospitalisations. A medical professional recently told me: ‘Whatever you’re doing, keep doing it.’ And I do. I hike at least an hour every day, and I choose to perform manually even the most rigorous tasks. I snowplough the nearly quarter-mile trail to my cabin with a push sleigh shovel rather than rely on a more convenient but noisy, expensive and troublesome plough truck. I split logs by hand rather than use an electric log-splitter. This past summer, I painted the exterior of the cabin by brush instead of using a paint-sprayer. The benefits I draw from these practices go far beyond my physical and emotional wellbeing. This physical, manual work immerses me deeper into this land, heightens my connection with this place, enriches my soul. When I split firewood, I pause to inhale the pine smell. I admire the vastness of the mountain landscape. I plan excursions to explore the mysteries hidden inside its thick forest. Clearing snow as it softly falls all around me, I’m alone inside the deepest silence the mountain offers.

While this life can be contemplative, it is by no means pastoral. It’s not even particularly safe

Sometimes, I wrestle with this choice I’ve made. At a very basic level, I’ve become intolerant of noise. Away from the mountain, common sounds (a car door slamming, playgrounds, copy machines, even people coughing) are magnified. My senses are easily overwhelmed. Apart from food, I mostly shop online to avoid the barrage of colour and activity in retail stores, even when this costs me more. I’m only 54 miles from Denver, yet over the years I have been visiting less and less; with their advent, DVDs have replaced even annual trips to a movie theatre, let alone the concerts and cultural events I used to enjoy. Sometimes, too, I regret not having children, but I couldn’t raise them alone on the mountain, and my desire to have children wasn’t strong enough for me to choose to marry and relocate. As one disappointed suitor said: ‘What are you going to do, die on this hill?’ Perhaps. If I do, it will be with full knowledge that the primary relationship in my life has not been with a person, but with a mountain.

Approaching the three-decade mark, I wonder: is this self-imposed solitary life a necessity, an indulgence, or a form of madness? I’m not quick to dismiss any of these possibilities. Steep cliffs, roads without guardrails, blizzards, wildfires, and close encounters with black bears and mountain lions remind me that, while this life can be contemplative, it is by no means pastoral. It’s not even particularly safe. Last spring, during a ferocious windstorm, a tree split in half and struck the cabin; two months later, a lightning strike set the deck on fire. I was inside the cabin on both occasions; each time, I was lucky to escape unharmed and that the damage to the cabin was minor.

Over the years, I’ve come to view my relationship with this mountain as a marriage, and like a marriage, sometimes I want a divorce. Self-reliance can be emotionally and physically draining. It’s always me paying the bills, replacing ageing infrastructure, chaining up the truck tyres, stocking the woodpile, and ploughing the heavy, back-breaking late-fall and early spring snows. Five years ago, I fell over inside the cabin, and as I lay on my back on the floor, literally seeing stars in the darkness, I grasped in full the vulnerability that comes with solitude. At night, the darkened windows reflect my shadowy self as I move from room to room in the silent cabin. Twenty or so years ago, I joked that my goal in life was to haunt the mountain after I die. I no longer make that joke. Recently, on a particularly cold winter’s night, I watched the film I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House (2016). Forget close encounters with mountain lions – that film terrified me, especially with its quiet conclusion: ‘Surely this is how we make our own ghosts. We make them out of ourselves.’

And still, I remain.