It’s often thought that philosophy begins and ends with abstract and rational thinking. Like science, it’s seen as a methodology of logic that allows the philosopher to be detached, disengaged, free from the irrationality and subjectivity of emotion, and precise in the pursuit of objective truth. However, the history of philosophy shows that disruptive emotions and moods are central to the experience of philosophising. Philosophy means love of wisdom. It includes a care of the self, and our attitude towards the world is extremely important for wellbeing.

Perplexity, wonder, surprise, estrangement and existential anxiety are some of the disruptive moods that spark philosophical reflection. For example, it is often the case that in the grief following the death of a loved one, we find ourselves asking philosophical questions: What is it all for? What does it mean to exist?

There is a pattern in the history of philosophy that allows us to identify moods as the trigger that calls for and sustains philosophical reflection. Although not every philosopher is inspired by a disruptive mood, many of them are. Plato’s Socrates speaks about himself as being perplexed and lost. Michel de Montaigne writes about the melancholia, deepened by the death of a dear friend, through which he came to philosophy. René Descartes’s methodological doubt emerged out of a sense of insecurity experienced in the disruption of his Catholic taken-for-granted beliefs. Karl Marx’s politics meant he was alienated from conventional ways of being-in-the-world. Søren Kierkegaard’s anxiety led him into the world of philosophical reflection (‘all existence makes me anxious,’ he once wrote). Friedrich Nietzsche writes of the relationship between his emotional pain and his philosophy. While Martin Heidegger does not write of his own anxiety, much of his thinking arose in response to a disillusionment with technology and modernity. Max Weber experienced the depression of a disenchanted world.

Different moods disclose and frame the world in different ways. In the mood of perplexity, Socrates becomes attuned to an understanding of virtue, while Plato sees wonder as the horizon of metaphysical thinking; wonder, for Aristotle, is the basis of enquiry into what is. In a mood of disenchantment, the Romantics launch their great project of re-enchanting the world, and the Marxists take alienation and estrangement to be the revolutionary basis for the liberation of workers from the capitalist class. Kierkegaard understands his own profound anxiety as the trigger for moving beyond the finite to the world of possibility. Nietzsche shows us that the anguish of nihilism leads to the re-evaluation of all values, while Heidegger finds a different lesson in anxiety, taking us beyond the ‘average everyday’ ways of being to an ‘authentic’ attunement to being. In general, existential philosophers see the mood of the anxiety of meaninglessness as throwing us into the scary and exciting question of meaning.

By emotionally disrupting the familiarity of our everyday world, these moods of disruption allow us to step back, to question, to make sense of that world in new ways. The familiar world becomes explicit to us – no longer presumed but provoking – and we can question the ways of our being in that world. When we engage in philosophical questioning, we are questioning the way in which we make sense of our own existence, the existence of others, and our relationships to them. In reflecting philosophically, our way of being in the world is at stake.

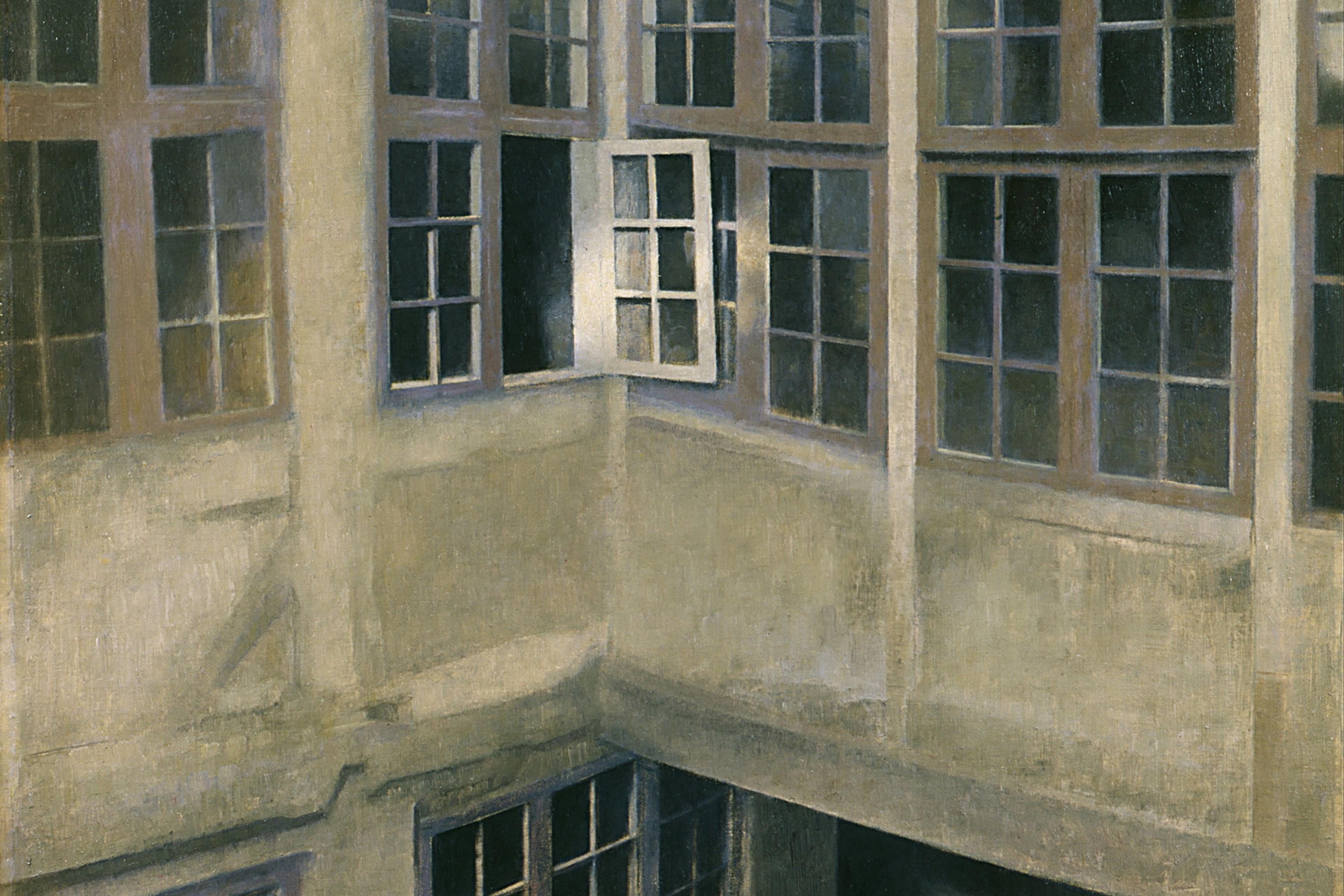

The images that they once took to be real are just the shadows of objects

Plato’s allegory of the cave illustrates just this kind of disruption. He asks us to imagine a group of prisoners chained to the floor of a cave since infancy. They can look only straight ahead, since their chains prevent them from turning around. The things that pass by the entrance of the cave behind the prisoners cast shadows on the wall in front of them. All they’ve ever known are the shadows: they assume, naturally, that what they see is the real. This is their familiar, everyday world.

Then the chains of the prisoners are removed – the searing disruption of their lives. For the first time, they can turn around and see what is behind them: the light at the entrance to the cave. Now they can see that the images that they once took to be real are just the shadows of objects – not the objects themselves. They begin to be able to make a distinction between the image of things and the physical reality of things.

Their whole sense of what is real is disrupted. They are perplexed and confused, and experience the uncertainty of not being able to take their usual way of seeing the world for granted. For some of the prisoners, this creates too much anxiety, and they want to return to the familiarity of their old ways of being in their cave.

Others, however, are not only afraid but excited by what they are beginning to see behind them. It is still unfamiliar and strange, but it is exciting too. They are willing to embrace the journey into the strangeness of the unfamiliar. We can call this simultaneous experience of excitement and anxiety ‘anxietment’. Such ‘anxietment’ is the mood in which philosophical reflection starts to take shape.

In the state of ‘anxietment’, the former prisoners approach the entrance to the cave. They are in for another surprise: they begin to see that they were in a cave all along. When they were in the cave, they could hardly know that it was a cave they were in. It is only as they come out that all becomes clear.

This points to the distinctive nature of philosophical reflection: it is less about observing the shadows that are projected onto the wall of the cave and more about becoming attuned to the background context in which the shadows are situated. To see our cave is to notice the unstated assumptions, conventions and habits that shape our observations and day-to-day interactions with the world.

Different philosophers have different understandings of the background context to which we become attuned when, through embracing moods of disruption, we begin to venture outside the cave. For example, for Marx, workers in their day-to-day activities are not aware of how their way of being is shaped by capitalism and the historical material conditions of existence. Alienation is the mood of becoming emotionally dissociated from the world of work such that workers can see how their way of being at work is shaped by the relations of production in capitalism. For Heidegger, when we are absorbed in our average everyday ways of being-in-the-world, we do not even know that our way of being is shaped by average everyday customs and conventions. It is only through existential anxiety that we are emotionally abstracted from our everyday engagements in the world such that we become attuned to the background conventions and ways of doing things that had shaped our way of being-in-the-world. ‘Only when the strangeness of what-is forces itself upon us,’ he writes, ‘does it awaken and invite our wonder. Only because of wonder, … does the “Why?” spring to our lips.’

When we are struck by wonder, the language of the question to be asked is not yet formulated. It gets formulated as we stay in the surprise and mystery of wonder. As Heidegger says, the ‘why’ question emerges through the mood of wonder.

I do not work with ‘neurotic’ anxiety in the same way as I work with existential anxiety

Psychologists and psychotherapists know this point well. Clients come into therapy because they are experiencing moods that they cannot easily put a name to. Working through the feelings of anxiety and depression offers clients the opportunity to name the experience and develop the language with which to enquire into the self. This process of formulating questions takes the skills of working through moods, learning to listen to what Eugene Gendlin calls the ‘felt sense’ of a mood – the sense that something is not quite right, disturbing us even though we cannot quite say what it is.

The challenge for philosophical and psychological reflection is to develop the sensitivity to identify the particular mood of disruption and the world that is opened through the felt sense of that mood. Different moods trigger different mindsets. For example, as a psychologist, I see many clients experiencing ‘neurotic’ anxiety, and I see other clients that experience the anxiety of the pointlessness and meaninglessness of existence. Each form of anxiety emerges out of different moods. I do not work with ‘neurotic’ anxiety in the same way as I work with existential anxiety. In my formulation, neurotic anxiety is about mental blocks that inhibit a person from achieving what they wish to achieve, such as a talented musician who feels the frustration of being too scared to perform. In existential anxiety, a person has lost all sense and meaning of being a musician. They are not scared of performing, rather there is a felt sense of a loss of the point of being a musician. Embracing the anxiety of meaninglessness is the clue to working through existential anxiety, while neurotic anxiety is worked through by identifying conflicts within the intrapsychic self.

Then there is another kind of alienation and estrangement that leads to a different framing. For example, bell hooks writes about her feminist thinking arising out of a sense of estrangement from the familiar and taken-for-granted conventions of her cultural context. This alienation allowed her to catch sight of, critique and liberate herself from the dominant patriarchal values. In my psychotherapy practice, I also see men who, in the bewilderment of estrangement, are living through questioning their attunement and ways of being a man, desperately trying to embody new ways of being in relationships.

The point is that there are many forms of mood disruptions, each disclosing a different form of philosophical reflection. It is crucial to develop the ‘phenomenological sensitivity’ to follow the path that arises out of each form of disruption. Philosophical reflection is about allowing that which emerges in moods of disruption to be made explicit for thought in all its forms: therapeutic reflection, critical reflection, reflexive thinking, thoughtfulness and pondering. Because philosophical reflections work with the moods of disruption, such reflection integrates thought and mood. It is neither subjective nor objective. Thinking always takes place in a mood.