Millennials – the much-maligned generation of people who, according to the Pew Research Center, were born between 1981 and 1996 – started turning 40 this year. This by itself is not very remarkable, but a couple of related facts bear consideration. In the United States, legislation that protects ‘older workers’ from discrimination applies to those aged 40 and over. There is a noteworthy irony here: a group of people who have long been branded negatively by their elders and accused of ‘killing’ cultural institutions ranging from marriage to baseball to marmalade are now considered ‘older’ in the eyes of the government. Inevitably, the latest round of youngsters grows up, complicating the stereotypes attached to them in youth. More importantly, though, the concept of a discrete generation of ‘millennials’ – like that of the ‘Generation X’ that preceded these people, the ‘Generation Z’ that will soon follow them into middle adulthood, and indeed the entire notion of ‘generations’ – is completely made up.

As an industrial and organisational psychologist, I have dedicated my career to the scientific study of people at work. I often have conversations with people about my research, and when I tell them that part of what I do is to study the idea of generations and generational differences at work, I typically get one of two reactions. Most often, people react by telling me about the various things that their younger or older coworkers ‘do’ because they are (assumed to be) a member of one generation or another. For example, and reflecting common age-based stereotypes, I often hear complaints such as ‘My millennial coworkers are all so entitled and self-absorbed!’ or ‘My boomer coworkers are all so rigid and set in their ways!’ Less often, people react with a more sceptical tone, questioning whether there is truth behind the ideas they have heard about generational differences. Either way, these conversations generally lead me to explain that research suggests there is little evidence for the existence of actual generations. This response is often surprising to those who have been inundated with ideas about generational differences and have accepted their existence at face value.

The lack of evidence stems primarily from the fact that there is no research methodology that would allow us to unambiguously identify generations, let alone study whether there are differences between them. We must fall back on theory and logic to parse whether what we see is due to generations or some other phenomenon related to age or the passing of time. In our research, my colleagues and I have suggested that, owing to these limitations, there has never actually been a genuine study of generations.

Generally, when researchers seek to identify generations, they consider the year in which people were born (their ‘cohort’) as a proxy for their generation. This practice has become well established and is usually not questioned. To form generations using this approach, people are rather arbitrarily grouped together into a band of birth years (for example, members of one generation are born between 19XX and 20YY, whereas members of the next generation are born between 20YY and 20XX, etc). The problem with doing this, especially when people are studied only at a single point in time, is that it is impossible to separate the apparent influence of one’s birth year (being part of a certain ‘generation’) from how old one is at the time of the study. This means that studies that purport to offer evidence for generational differences could just as easily be showing the effects of being a particular age – a 25-year-old is likely to think and act differently than a 45-year-old does, regardless of the ‘generation’ they belong to.

Alternatively, some studies adopt a ‘cross-temporal’ approach to studying generations and attempt to hold the effect of age constant (for example, comparing 18-year-olds surveyed in 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, etc). The issue with this approach is that any effects of living at a particular time (eg, 2010) – on political attitudes, for example – are now easily misconstrued as effects of having been born in a certain year. As such, we again cannot unambiguously attribute the findings to generational membership. This is a well-known issue. Indeed, nearly every study that has ever tried to investigate generations falls into some form of this trap.

Recently, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in the US published the results of a consensus study on the idea of generations and generational differences at work. The conclusions of this study were clear and direct: there is little credible scientific evidence to back up the idea of generations and generational differences, and the (mis)application of these ideas has the potential to detrimentally affect people regardless of their age.

Where does this leave us? Absent evidence, or a valid way of disentangling the complexities of generations through research, what do we do with the concept of generations? Recognising these challenges, we can shift the focus from understanding the supposed natures of generations to understanding the existence and persistence of generational concepts and beliefs. My colleagues and I have advanced the argument that generations exist because they are willed into being. In other words, generations are socially constructed through discourse on ageing in society; they exist because we establish them, label them, ascribe traits to them, and then promote and legitimise them through various media channels (eg, books, magazines, and even film and television), general discourse and through more formalised policy guidance.

We must also ask ourselves, what accounts for the ubiquity of generations? This is a complex question, with multiple answers. The simplest one, perhaps, is that generations persist because they are a convenient (albeit imperfect and misguided) heuristic that appears to help us make sense of the complex phenomenon of ageing. Thinking about age in terms of generations takes an otherwise complicated task – determining how age matters for the types of everyday social interactions that we have with people of different ages – and reduces it to remembering a few groups with known characteristics that can be readily mapped on to social behaviours.

With generational labels and concepts in hand, people start to seek out the relevant behaviours in others. If we think that people from ‘Generation A’ are supposed to act entitled and narcissistic, then we will likely treat them as such. Generations and the assumptions that we make about them create a lens through which we interact with others, shaping various forms of social behaviour. The lens of generations also shapes how we view our own behaviour, and it is possible that some people internalise the role prescribed to them by their generational label and the stereotypical ways of thinking, feeling and behaving that are associated with it. For example, it is a common misconception that members of younger generations are more narcissistic than members of older generations. Importantly, this belief does not necessarily apply to one generation versus another, but reflects a stereotype associated with youth in general. If we are to believe that members of a certain generation possess increased levels of narcissism, then we are likely to seek out and focus on those behaviours that could be classified as narcissistic. In doing so, we might start to act differently toward such individuals, and perhaps in ways that encourage narcissistic behaviour or at least self-perceptions. Research suggests that simply reminding people of their membership in one generation versus another can affect their self-reported levels of entitlement, a facet of narcissism.

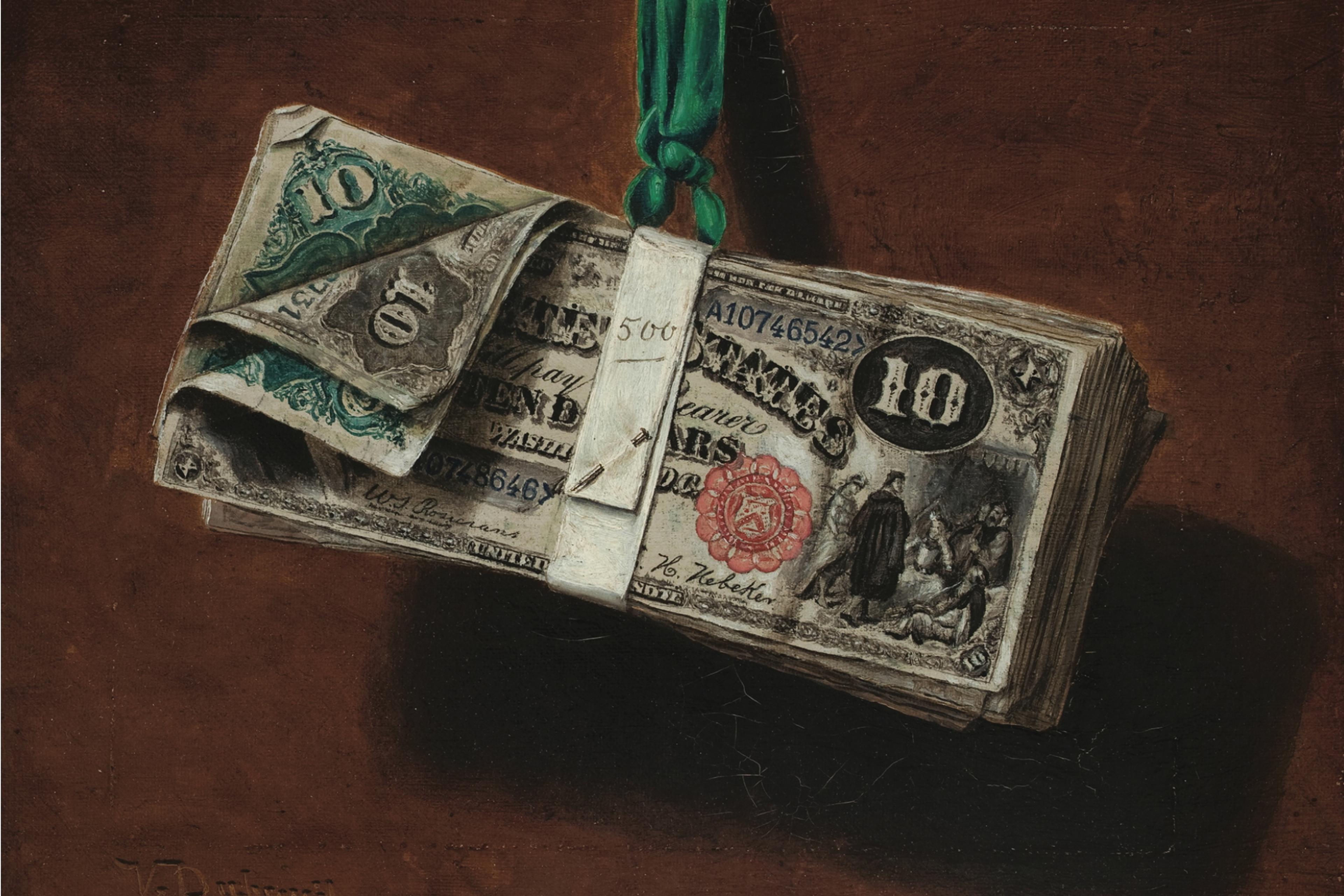

The ubiquity of generations can also be attributed to their value as a commodity; promoting generations and generational differences is big business. However, the idea of generations is really a modern form of snake oil – an easy way to explain the ills that plague organisations, institutions and society as a whole. Indeed, there are companies that have built their entire brand on the basis of shifty generations science, including market research firms and consultancies, and self-proclaimed generations ‘gurus’ who encourage differentiating people based on their assumed membership in one generation versus another. Social scientists have been pushing back against these ideas for some time. As of late, such efforts have come to a head, with the sociologist Philip Cohen organising an open letter co-signed by nearly 150 social scientists that implores the Pew Research Center to stop using generation labels.

The most important thing to remember is that generations as we know them are not really a thing. Most of what is assumed to be a generational effect is more likely due to age effects (the influence of individual development) or period effects (the influence of one’s current time and place), or probably some combination of age, contemporaneous time and other contextual and individual characteristics. What this means is that understanding the complexities of age differences is a far more difficult task than simply stratifying people based on their birth years and comparing them with one another. A more complete understanding requires us to individuate people in a more nuanced way. This is the approach that my colleagues and I have promoted in our advancement of a lifespan perspective to thinking about ageing and work. Adopting a lifespan perspective requires recognising that there are multiple co-occurring and related sources of influence (including biological, psychological and social influences) that shape one’s developmental course across one’s lifetime.

Thinking in this way about ageing in society has many advantages, not least of which is avoiding the pitfalls of generationalism – believing that all members of a given generation possess characteristics specific to that generation, especially so as to distinguish it as inferior or superior to another generation. Generationalism can be viewed as a kind of socially sanctioned ageism that has the potential to negatively affect people, young and old. Curtailing generationalism will not be an easy task. Indeed, intergenerational conflicts have long existed, and there will always be a market for generational ideas (there are now self-help books available for the victims of generational warfare). Considering the state of our understanding of this phenomenon, however, we would be well served to quit leaning on simplistic generational concepts to make sense of a complicated social world.