A few years ago, I had a breakdown from what would now be termed ‘burnout’. It was probably related to the early death of my father after a long-term illness when I was 12, and from which I had escaped into stories and poetry. As I lay in bed convalescing, I turned to books again, reading through the whole of the Raj Quartet (1966-75) by Paul Scott. His richly layered plot and superbly drawn characters in an Indian setting undoubtedly helped me to recover.

There have been other occasions in my life when reading has been more than simple escapism. A partial loss of hearing in my 30s when I was teaching in schools caused me to resort to hearing aids, which I found extremely difficult. However, I found salvation in Benjamin Zephaniah’s memorable poetry reading at the Hay Festival in Wales at a time when I was testing out modern hearing aids. Zephaniah invited his audience on to the stage to dance to the music of his poetry collection The Dread Affair (1985) – and we did.

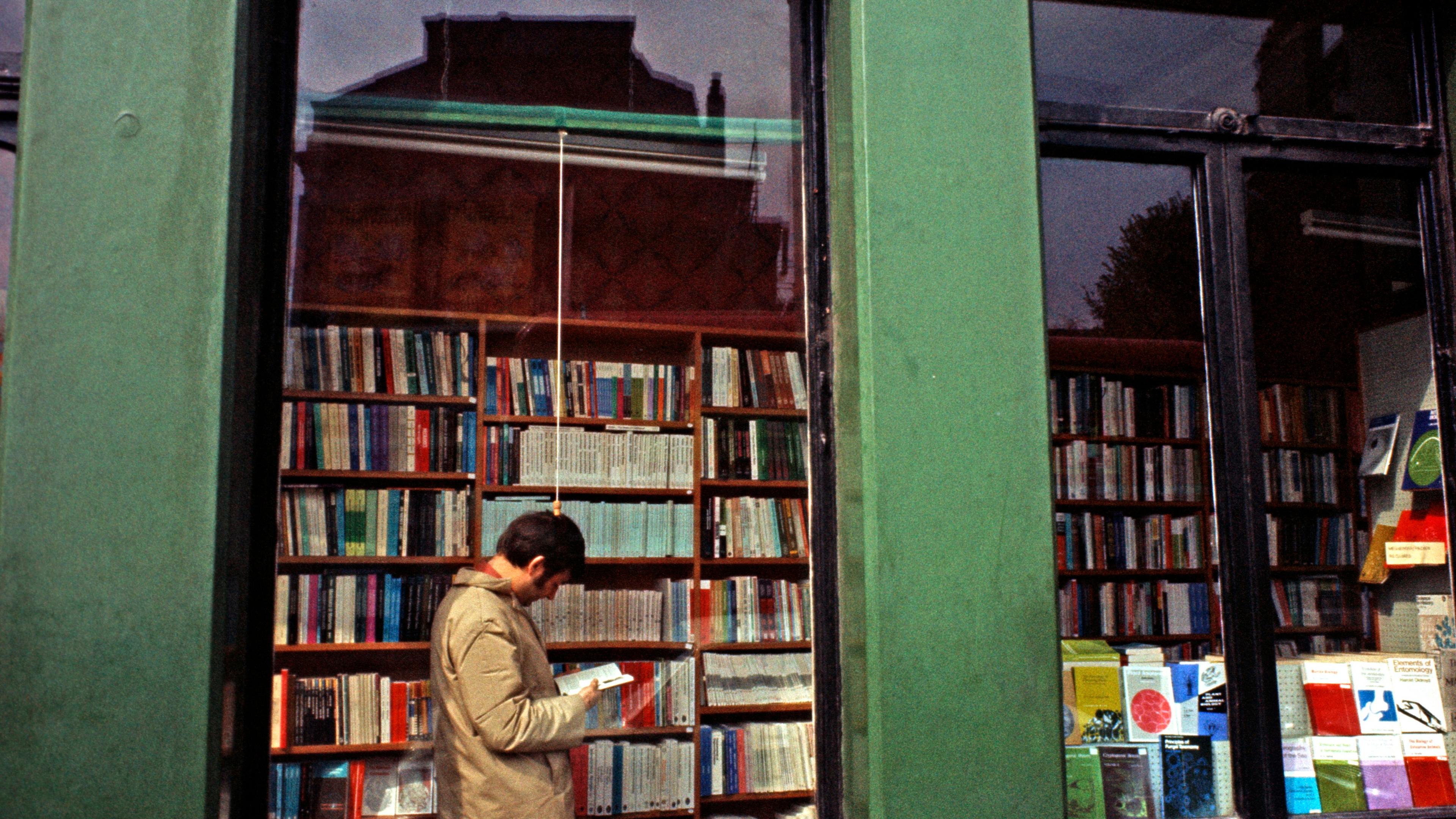

When I could no longer hear the children clearly, I left the school classroom and became a teacher of adults. After delivering a number of successful courses on poetry and novels, which I had devised myself for diverse adult groups, I decided to research ‘bibliotherapy’. The theory of bibliotherapy is that people engage with literature, not just to escape the familiar world and travel somewhere else, nor only for academic purposes, but to ease the pain of existence, of being human. I discovered researchers investigating the concept, such as Kelda Green, author of the thesis ‘When Literature Comes to Our Aid’ (2018), and practising bibliotherapists, such as Ella Berthoud and Susan Elderkin who wrote The Novel Cure (2013). I also came across an online book-therapy course, run by the author and journalist Bijal Shah. But I wanted to find out for myself whether there was any truth in the theory of bibliotherapy.

I asked for funding from the Workers’ Educational Association (the WEA), my employer at the time, to run a free, 10-hour course that I called ‘Reading Can Enhance Our Lives’. The WEA was founded in the UK in 1903 by Albert and Frances Mansbridge. They created a generation of self-educated men and women or ‘autodidacts’, and this movement would bring education to working people. I devised the course with the help of a local group of WEA students, one of whom offered: ‘Reading poetry and novels can lift us out of our everyday experience and give us pleasure, mental stimulation, a sense of wellbeing and company.’ I used this in the course advertisement, and recruited a group of 12 men and women. Most were over 50, but one or two were younger.

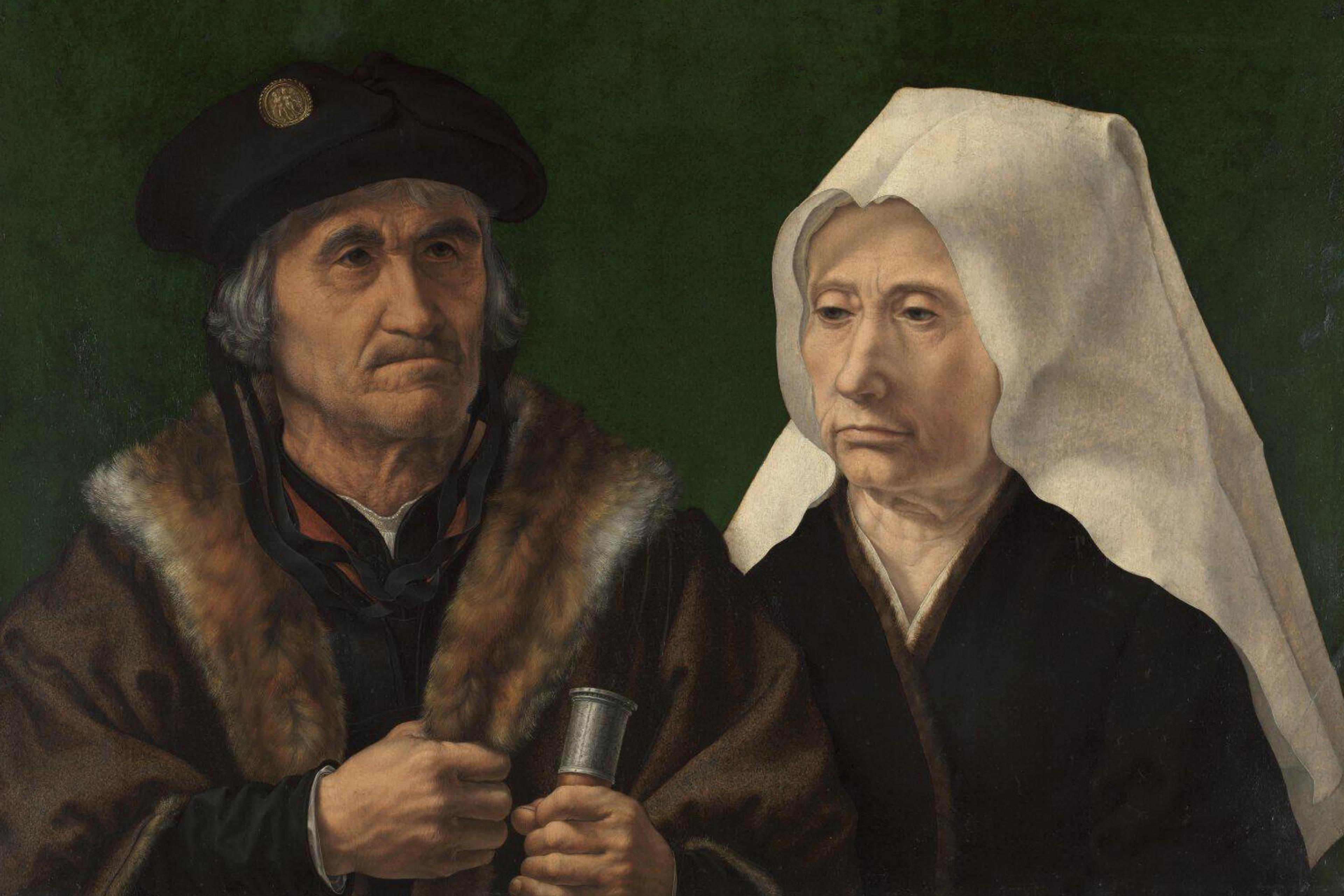

I spoke to the class about the theory of bibliotherapy. I told them it has been around for many years and that one of the first writers to say that reading books could comfort somebody after a heartbreak or a bereavement was the 16th-century French philosopher Michel de Montaigne. Writing after the death of a close friend from the plague, Montaigne said that the best therapy was the companionship of books. Plato too said that the arts could bring the soul circuit back into balance after a severe dislocation. And George Eliot, who used readings of Dante to get over the death of her husband, said that: ‘Art is the nearest thing to life; it is a mode of amplifying experience and extending our contact with our fellow-men beyond the bounds of our personal lot.’

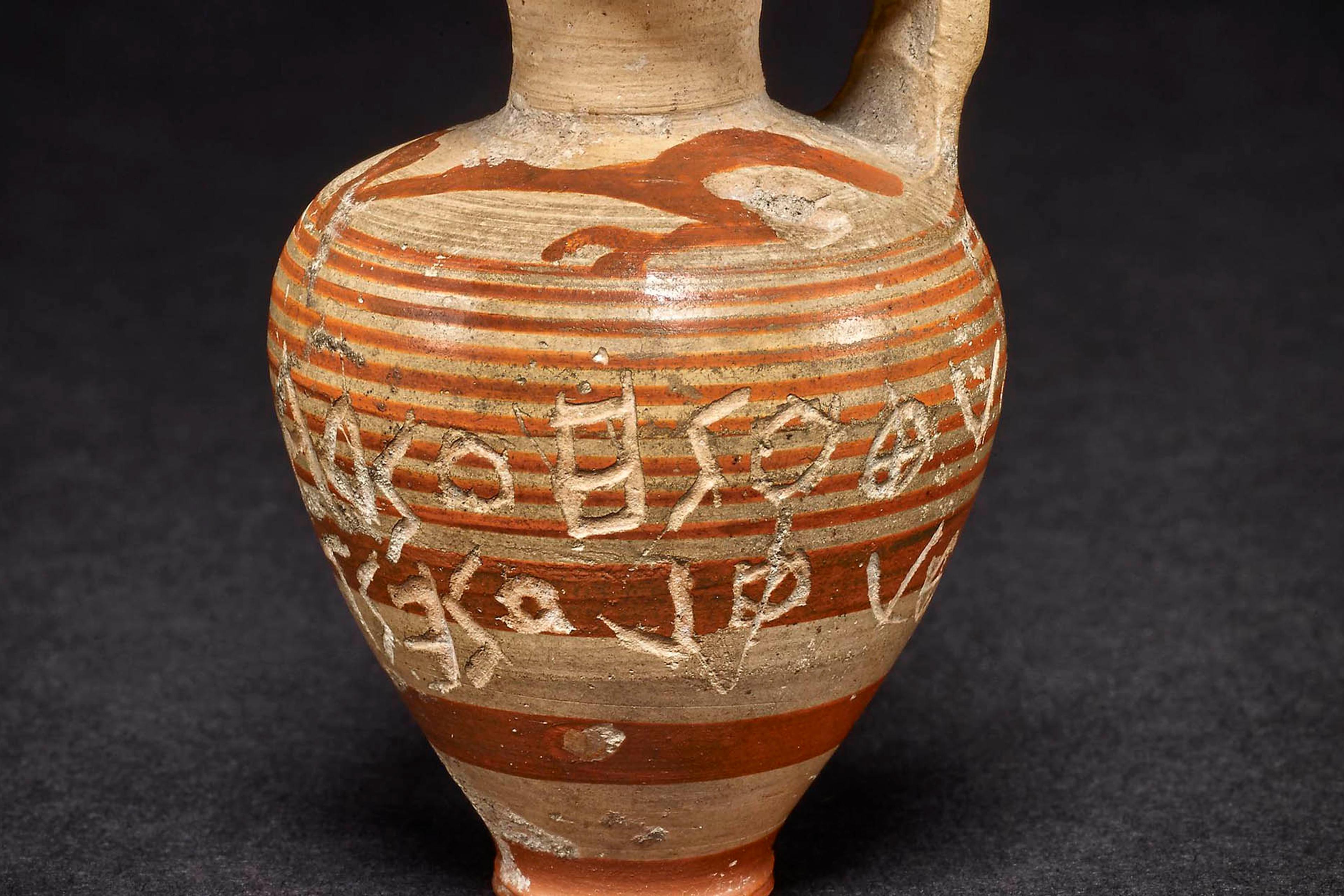

Another example I shared was the poet William Wordsworth, who wrote about how he found ‘spots of time’ in poetry where one could recover from life’s stresses and restore and repair oneself. More recently, at their presentation on bibliotherapy at the Cambridge Science Festival in 2019, the English scholars Edmund King and Shafquat Towheed quoted Second Lieutenant Stephen Henry Hewett, killed in action on the Somme in 1916, who wrote: ‘I am able to keep the spirit in me alive by constant reading. I have read so many fine books: a Russian novel full of sordidness and depression but made sublime by what Russian writers call the religion of Pity …’

Having given my students this introduction, I wanted them to have practical experience of the theory of bibliotherapy. Following an idea by Robert Macfarlane in The Gifts of Reading (2016), I asked them to bring in a book that they would give as a gift to a friend, relative or new acquaintance. I expected them to bring a stack of novels, so I was surprised that there was only one, a crime novel by Stephen Booth, a local writer. They brought books that I had not heard of such as The Shepherd’s Life (2015) by James Rebanks, Prisoners of Geography (2015) by Tim Marshall, and The Three Faces of Christ (1999) by Trevor Dennis.

After this, I talked about the use of written memoir as a means of making sense of our lives. I referred to a piece by a member of the group about herself and her love of reading, which she’d shared with me earlier. I then showed the group an article in The Guardian by the author Louise Welsh about how reading Maya Angelou’s memoir I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969) had made her think hard about the life that Angelou had lived. For the next session, I asked them to bring in a book that had affected them deeply.

The class divided into groups and discussed what they had brought. Among their choices were the case histories of a neurologist, a book about silence, books remembered from childhood reading, a book of songs and lyrics, a book described as ‘a haunting poetic story’ by a Pulitzer Prize winner, and a book about French wines. The discussion was upbeat, and I listened with fascination to the 12 stories that people told, about their memory of the effect that reading a book had had on their lives. ‘Reading gives us access to a range of experiences and emotions that we would not have had otherwise,’ said one.

Some students had found it difficult to choose a book, and I realised that they needed to be able to interpret the course requirements as widely as possible. This became even clearer in the next session when I asked them to choose a poem, special to them, to read and talk about to others in the group. I went first, reading aloud a poem called ‘Because You Asked about the Line Between Prose and Poetry’ by Howard Nemerov (1980). I then used a random-selection teaching method so that whoever felt like it could talk about their choice. Some gave out copies of poems they had printed, others read their poem aloud – conveying their feelings through their voices and the rhythms of their speech.

The idea of randomness worked well. As each student read and each poem was discussed, the next seemed to follow with no prompting from me. One student read the lyrics of the Beatles song ‘In My Life’ (1965); another, whom I had thought might not have the confidence, read the words of Robert Frost’s ‘The Road Not Taken’ (1915); one read an extract from Victor Hugo’s novel Les Miserables (1862), which had been shared together with a former partner many years before; yet another read the words of a Leonard Cohen poem, ‘Nightingale’ (2004), also in memory of a partner. Most contributed, although one asked me to read a poem on her behalf, which began: ‘Over what bones is built my house…’ I imagine it was very personal: ‘It is therapy, and for a short spell good to be alive,’ she had written in a prior statement given to me to share with the group during the readings.

I found the poetry session incredibly moving and called a break, suggesting that people move around the room. I certainly needed to. The level of trust between tutor and student required to enable such a sharing cannot be overstated. The presentations had shown me how important the idea of bibliotherapy could be for people’s lives and their future mental health.

As well as my own personal experience of how bibliotherapy can address mental health problems, I have also attended a course about it run by the WEA in the context of dealing with workplace stress. During this course, when I was asked for a list of books that might be useful, I recommended One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962) by Ken Kesey; The Bell Jar (1963) by Sylvia Plath; and the aforementioned Novel Cure.

The Novel Cure suggests specific books for specific conditions such as unemployment, worry, writer’s block and, most interestingly, ‘being married’ and the struggle to maintain one’s sense of self in the face of constant compromise. The suggested cure for ‘being married’ is a novel called The Enchanted April (1922) by Elizabeth von Arnim, in which two women decide to rent a house in Italy from where they can escape the inertia that they are experiencing in their married lives. They are joined by two other women who are single, and a wonderful series of encounters begins.

I thought that ideas from The Novel Cure might provide a good focus for the fourth session of my course, but when I gave the class a quiz, asking which books would be suitable for particular emotional conditions, I found that the idea was not as popular as I had expected. This made me reconsider the final session, and I decided to make it student-centred. When I asked what they wanted to do, one student suggested that everyone write a couple of sentences about how reading makes a difference to their lives, referring to examples if they wished. Everyone agreed to this, and the next week they read out their ideas and we discussed them. Here are some examples from that final session:

In my personal life, I feel I have received an enormous gift because, since I was a child, I have been able ‘to go through the back of the wardrobe’. I am able to dispense with any consciousness of words and to inhabit certain books … It is magical, and I am so grateful for it.

I find solace in books, quite easily becoming one of the characters as the pages turn … Family, friends are kind but in the modern changed world everyone is so busy … But there are highlights, being part of a group of people who enjoy and do discuss any form of culture, poetry in particular.

Students felt that they wanted to prescribe their own reading rather than have it done for them, and there was a range of further comments on what literature did for them such as: ‘It was an opportunity to step inside another mind.’ ‘It brought you out of yourself into a different world.’ ‘It can make someone who belonged nowhere belong somewhere.’

The course finished. Then the COVID-19 pandemic arrived and the group was unable to meet for more than a year. A small number decided to join up together as friends on Zoom. We would share the poems of a selected writer each week, the most recent being the poet Gillian Allnutt. I can compare this with an online book club that I am a member of, run by the UK organisation Carers First, where the participants had come together because they were responsible for looking after someone with a long-term illness.

Both groups share the same essential dynamic for developing the understanding by which people can benefit from interacting with a novel or a poem. As one member of Carers First wrote (as part of our entry for a book club competition run by the Reading Agency):

We’ve come together through two things, which are being carers and sharing a love of reading. We all recognise how important self-care is and that books help you feel part of a bigger world. Which is why we choose to read diversely and share good reads with each other.

This is not a statement about therapy but about how one can simply enjoy reading as a way of moving forward in one’s own life. It echoes the WEA student’s comment about bringing you ‘out of yourself into a different world’. In short, bibliotherapy is about discovering ways to divert and even heal our minds through reading. It’s about the power of finding the right book at the right time, as I have experienced in my own life. When embedded in a shared educational or social framework, be that an educational course or online book group, I’ve seen for myself that bibliotherapy can offer immense benefits for people’s mental and emotional health.