Last night, my daughter and I curled up under a blanket together and read Under the Same Sky (2017) by Britta Teckentrup. It’s a sweet picture book about how we’re all fundamentally similar to one another. It begins: ‘We live under the same sky, in lands near and far. We live under the same sky, wherever we are. We feel the same love in the cold ice and snow. We feel the same love where soft meadows grow…’

Eighty years ago, a German mother and daughter might well have curled up under a blanket in much the same way but with a very different children’s book, Der Giftpilz (1938) by Julius Streicher, which translates as The Poisonous Mushroom. Whereas the cover of Teckentrup’s book depicts two loving foxes, Streicher’s cover features hideous caricatures of Jewish men in the form of toadstools and, in the text, he describes Jews as a plague and as devils.

The Poisonous Mushroom is often cited as an example of dehumanisation – a tendency to see outsiders as less human. According to consensus opinion among psychologists and other commentators, members of outgroups are often viewed as closer to animals or machines than to fellow beings deserving of care. Moreover, these experts believe that dehumanisation lies at the heart of intergroup harm. The Nazis could never have sent men, women and children to Auschwitz if they had recognised their common humanity, so the argument goes.

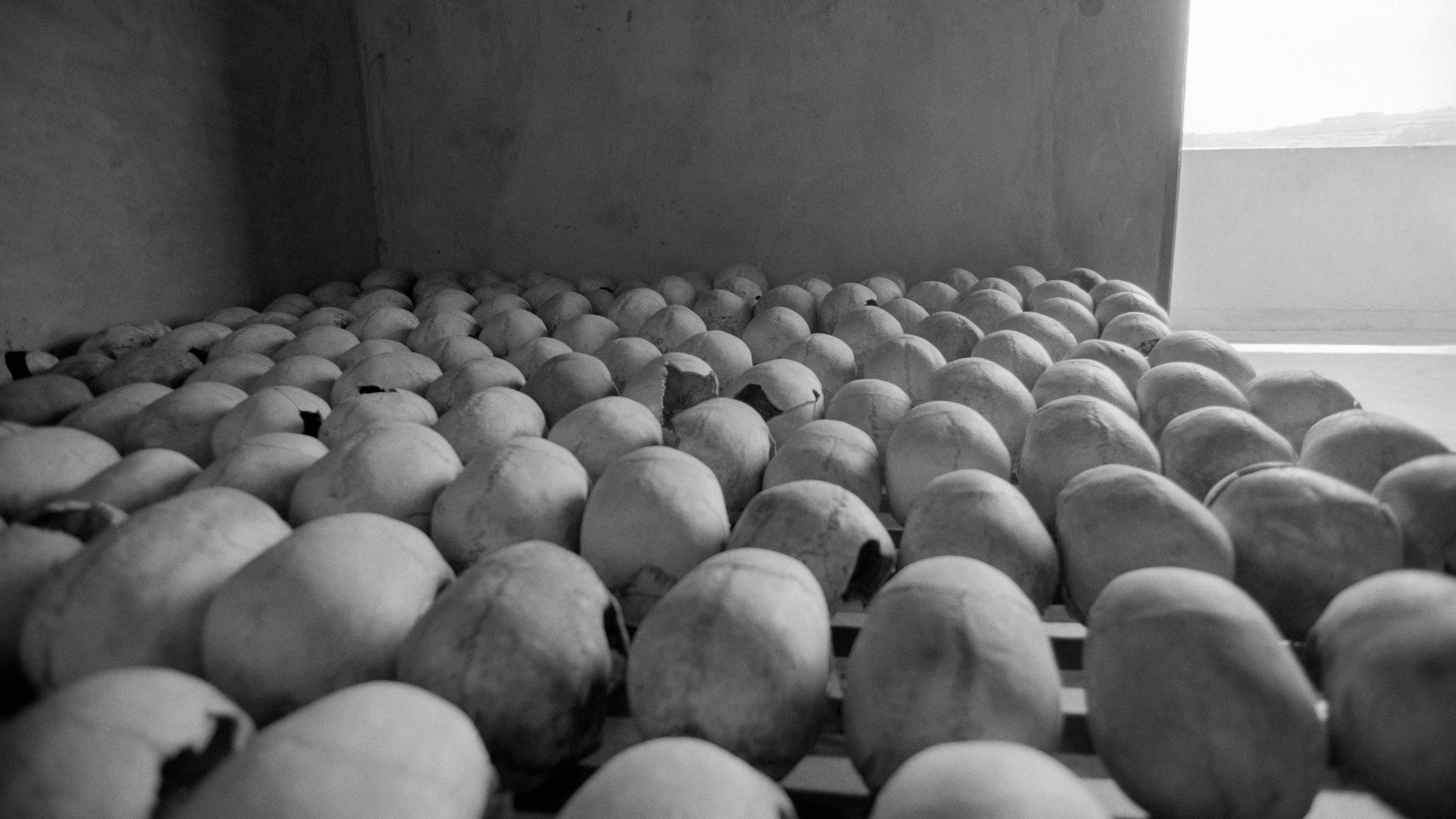

It’s an intuitively compelling idea. When advocates of dehumanisation cite examples, such as The Poisonous Mushroom, that are so powerful, so emotionally evocative, it is difficult to question them. In his book Less Than Human (2012), the philosopher David Livingstone Smith collated many similar historical cases, where the perpetrators of extreme intergroup harm described their victims as less than human, including the Hutu genocide of Tutsis in Rwanda in 1994, and the oppression of Black Americans by whites under slavery in the American South.

None of us are exempt from these forces. In contemporary Western societies, it’s not uncommon to hear immigrants referred to as a ‘swarm’ or an ‘infestation’. Psychological research also suggests that dehumanisation is not the preserve of extremists. When volunteers are asked to rate the qualities of different groups, even those holding moderate political views will often subtly deny outgroups uniquely human qualities, such as civility, rationality and refinement. In studies of emotion perception, in which volunteers are asked to evaluate the emotional experiences of others, they report that outgroup members experience complex human emotions such as pride, admiration and guilt to a lesser extent than do their fellow ingroup members.

However, look more closely at the evidence, and the claim that outgroups are dehumanised loses some, perhaps most, of its explanatory value. There are two key problems. First, it’s not clear that outgroups really are perceived as less human than the ingroup. Second, even if outgroups are perceived as less human, it’s not clear why this should increase the risk of harm against them.

As noted by others, including the philosopher Kate Manne and the psychologist Paul Bloom, when people derogate outgroup members, they often describe them in ways that really make sense only when applied to humans. In The Poisonous Mushroom, for instance, Jews are described as liars, swindlers and rapists. Nazi propaganda is filled with similar examples. It makes sense to call a fellow human a swindler, but it doesn’t make sense to refer to an animal or a machine in this way.

Furthermore, although outgroup members are often described as similar to nonhuman entities, so too are members of ingroups. Look beyond the front cover, and the text of The Poisonous Mushroom reveals this to be the case: ‘Human beings in this world are like the mushrooms in the forest. There are good mushrooms and there are good people. There are poisonous, bad mushrooms and there are bad people.’ Jews are compared to mushrooms but so too are the non-Jewish German people.

Psychological research showing evidence of dehumanisation also faces conceptual challenges. Current models suggest that when people subtly dehumanise outgroups, they deny them uniquely human qualities such as civility, refinement and rationality. This might well be true, but what of more antisocial human qualities? Humans can be civilised, refined and rational but they can also be petty, spiteful and arrogant. In ongoing research in my lab, we asked volunteers about these negative qualities and found that they view them as unique to humans. Furthermore, they attribute these uniquely human qualities more strongly to outgroups than to their ingroup. My colleagues and I hypothesise that what appears to be evidence for dehumanisation might really be evidence for a more basic process of ingroup preference – believing that your own group possesses more positive human qualities and that other groups have more negative human qualities.

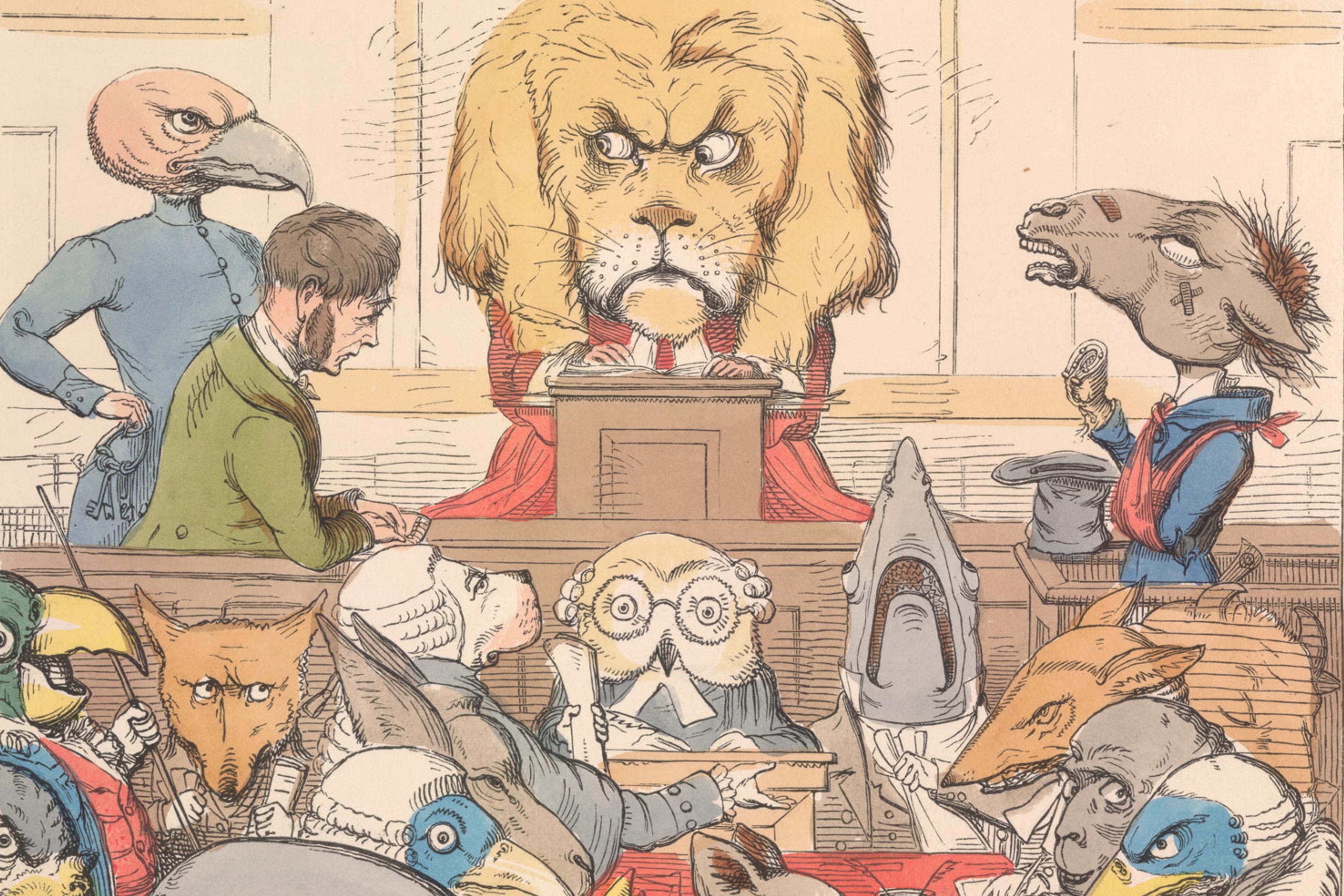

There are also challenges for neuroscientific research that purports to show evidence of dehumanisation. In a widely cited paper published in 2006, the researchers Lasana Harris and Susan Fiske argued that, when people dehumanise outgroups, they think of them as lacking mental states such as desires, beliefs and goals. Apparently supporting this view, the pair reported that when their research volunteers viewed pictures of outgroup members, such as homeless people or drug addicts, they exhibited less activation in brain areas associated with mentalising, particularly the medial prefrontal cortex. However, Harris and Fiske’s characterisation of dehumanisation is undermined by supposedly prototypical examples of extreme dehumanisation in which perpetrators appear to make mental-state inferences about their victims. For instance, Nazi propaganda is replete with references to what Jews were supposedly lying about and scheming to achieve. These references to Jewish people’s beliefs and goals were inaccurate and filled with malicious intent, but they were mental-state inferences nonetheless – to accuse someone of lying is to make an inference about what they are thinking.

What then of the claim that the dehumanisation of outgroups contributes to a willingness to harm them? Here too there is reason to be sceptical. Much research in this area is based on the assumption that, by undermining our recognition of each other as fellow humans, dehumanisation erodes the natural inclination we have to care for each other. But it is unwise to place too much faith in the human desire to protect and care for other humans. Indeed, outgroup members are sometimes harmed because of their perceived humanity. After all, only humans can be murderers, traitors and enemies – and murderers, traitors and enemies are seen as legitimate targets for negative treatment.

A second reason to doubt the supposed causal role of dehumanisation in harm is that many people have a powerful instinct to treat nonhuman animals with great care. Family pets, for example, are clearly ‘less than human’ and yet people lavish care, attention and money on them. Viewing a group as less than human, then, seems neither necessary nor sufficient for harming them.

My critique of dehumanisation as an explanation for intergroup harm has implications beyond academic debate. Inspired by work in this area, some researchers have started to develop interventions for social change that aim to reduce dehumanisation. Though well-intentioned, such efforts could be misguided. My analysis suggests that attempts to foster a more inclusive and egalitarian society might be better targeted at other well-established psychological processes, such as the human tendency to stereotype and derogate people seen as outsiders.