We are curious creatures. Not (just) strange, but eager for knowledge. We spend much of our waking lives seeking out and consuming information in some form or another: watching television, listening to podcasts, reading books or online articles, or prying the latest office gossip out of a co-worker. While some of this information is no doubt useful to us, plenty of it has little practical use – like wanting to know how a novel ends.

Humans are far from alone in our thirst for information. Even the tiny roundworms Caenorhabditis elegans, with only 302 neurons in their millimetre-long bodies, are known to seek out information about their environment. They likely do so only to improve their foraging, but our closer cousins, macaque monkeys, are willing to pay for information that isn’t useful to them. In laboratory experiments I performed as a grad student, monkeys would forgo a slightly larger reward to find out the outcome of a gamble a little earlier, even when that information couldn’t be used in any way.

Some researchers have suggested that curiosity is its own drive, like hunger or thirst. The idea being that, since it is hard to know what piece of information might come in handy in the future to help us satiate our other needs, evolution built in a drive to seek out information for its own sake, for us to accumulate in case it becomes useful.

But all this infophilia raises an important question: if we like information so much, why don’t we seek out more of it? Most of us are constantly surrounded by various machines and phenomena we have only the dimmest understanding of. As I write these words, in front of me is a microphone. How does a microphone convert sound, made up of waves of air, into an electrical signal? I have no idea. I similarly have no clue how the motor in my standing desk converts electricity into movement.

It isn’t just technology that raises these questions. How do the trees I see out of my window convert sunlight into usable energy? Other than the word ‘photosynthesis’, I wouldn’t be able to tell you. I have only a slight understanding of the chemical properties of water that make it act in its characteristic ‘wet’ way, allowing it to run over my hands, bead up if I have oil or lotion on my hands, and get easily absorbed by a towel.

I have access to vast amounts of knowledge through the internet. A simple search would turn up information that might dramatically improve my understanding of all these phenomena. And yet I’ve never once stopped to look up answers to these specific questions.

Humans are curious, but we are selectively curious. Of course, we can’t be curious about everything – each of us has limited time to indulge in information consumption. But why is it that we might be so driven to learn, say, the resolution of a TV plot but feel little compulsion to learn about how our devices work or other aspects of everyday life? What explains our particular patterns of curiosity?

When someone first starts learning about a domain – such as physics or ancient history – they have only a situational interest in it, according to the ‘model of domain learning’ proposed by the educational psychologist Patricia Alexander. That is, they will show interest in learning about the domain only if something external (eg, a teacher) draws their attention to it. As a learner develops more of a cohesive body of knowledge, they’re able to ground new learnings in that conceptual framework, and they become more intrinsically interested in seeking out information within the domain on their own.

Imagine picking up a thick textbook on the history of a country you know little about. It will mention the names of historical figures, cities, neighbouring states, and geological features like rivers and mountains. Even if you constantly refer to maps, you’ll quickly find it difficult to keep up with the tangled complexity of the topic. Without pre-existing knowledge – of the geography, for instance, or about other historical examples that you can make analogies to – you’ll have a difficult time coping with all of the complexity. The juice just won’t be worth the squeeze.

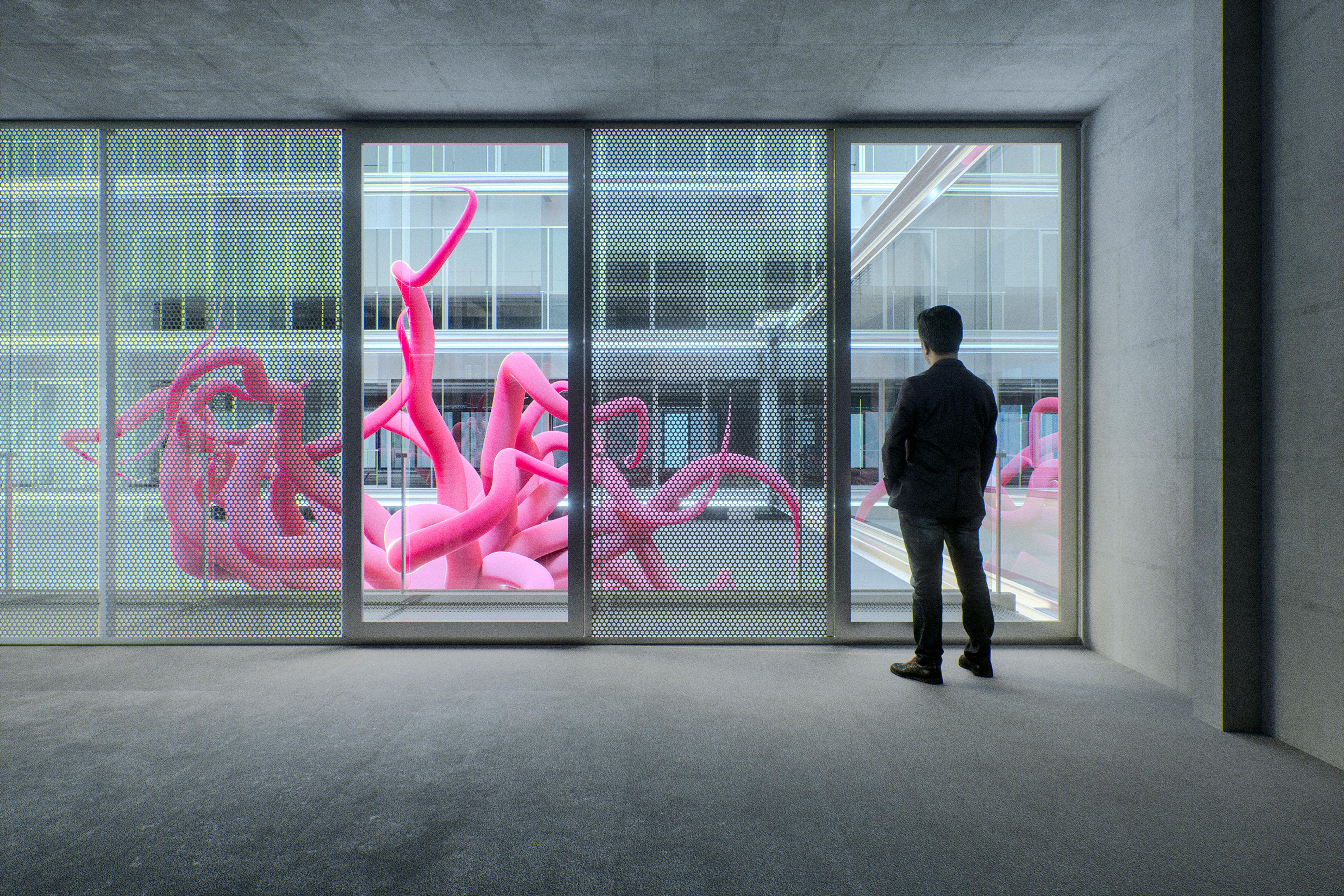

So a lack of curiosity in some areas may just be due to the cognitive difficulty of grasping the complicated concepts within them. This ties in with studies in the psychology of aesthetics. People are more drawn to art when it is more intricate – but only up to a point. At very high levels of visual complexity, art can become less appealing. Yet research has also shown that viewers with expertise in visual art are able to handle more complexity, and so prefer more complex artwork. People are drawn towards the right balance between complexity and their individual ability to cope with that complexity.

People are most curious about questions that they have some intermediate level of certainty about

Developmental studies have also found a ‘Goldilocks zone’ where the amount of complexity is just right. Infants have been shown to pay attention to events that are not too complex but also not too predictable. The developmental psychologist Celeste Kidd argues that this is because infants are looking for the middle ground between patterns that are too difficult to learn and patterns that are too predictable for there to be anything left to learn.

In adults, research on curiosity has shown another Goldilocks zone, but this one related to our levels of certainty about what we know. People are most curious about the answers to trivia questions that they have some intermediate level of certainty about. They are less curious when it comes to the questions that they’re highly confident about, presumably because they already know the answer. But they also report being less curious about a question when they have no clue what the answer is. This might be because, without any knowledge of the topic, the answer isn’t very meaningful: it doesn’t connect with any other knowledge one has.

Think about the question: ‘Who was the second prime minister of Canada?’ If you know nothing about any of the people who played big roles in Canadian history, you probably have no interest in the question – the answer is just a name. But if you do know some Canadian history, and your memory is a bit hazy, a couple of names might float to mind and your curiosity will be piqued.

This has led researchers to talk about curiosity as a drive to fill in gaps in our knowledge. When we notice a gap – like when we hear certain trivia questions – we feel the urge to plug it. If there isn’t a gap, but rather a total lack of knowledge, we don’t feel the same need. Our built-in hunger for information is directed towards information that we have the conceptual structure to properly digest. Pre-existing knowledge about a subject, by giving us plenty of scaffolding throughout the conceptual space of a domain, provides enough structure for there to be compelling knowledge gaps.

All of this might explain why we don’t pursue certain types of questions – those in domains where we lack information, in which we can’t see gaps in our knowledge or the complexity seems too high to cope with. But some of the objects around me are relatively simple, yet still I’m often surprised by how little I understand them. Why don’t I look up the mechanical principles of how a toilet works?

Part of the answer is certainly habituation: I’m aware of the objects around me, but I’ve seen them so many times that they don’t actively pull my attention towards them. I’ve become a bit numb to their presence. If I didn’t think to enquire about how they work the first time I saw them, it’s unlikely I will do so the thousandth time. The gap in my knowledge never comes to mind.

There are plenty of things we think we understand, but our understanding is actually fragmentary

But, in some cases, there is a more insidious explanation. Some questions are invisible to us because we think we already know the answer. Studies have shown that people are overconfident in their knowledge. They report knowing how a bicycle works, but when asked to draw how its different parts are linked together, many draw bikes that couldn’t possibly work – such as a bike with the chain connected to the front wheel, so that it wouldn’t be able to turn. People will report knowing what a coin looks like, but when asked to draw one, completely fail to accurately depict it.

In other studies, people have been asked to report how well they understand something. Then they’re asked to explain it. After trying to explain it, they rate their understanding again. Try it yourself: how well do you understand how a flush toilet operates, on a scale of 1 to 5? Now try to provide an explanation of it, and see if your confidence in your understanding changes. In the studies, people’s ratings of their understanding drop, as if attempting an explanation of something makes them realise how poorly they actually understand it.

In other words, there are plenty of things we think we understand, but if we were to actually think a little deeper about them, we would realise our understanding is fragmentary and shallow.

What this all means, though, is that there are unappreciated opportunities all around us to learn more about the world. To awaken your curiosity drive, it might help to actively seek out the gaps in your understanding of things or events that you encounter every day, when you’re at home, working or reading the news. Those areas where you know at least a little, but your mental picture is incomplete.

Developing some knowledge in a domain is an important way to open our eyes to new learning opportunities. But there are plenty of things within our personal Goldilocks zones of complexity that each of us could easily get more interested in. Sometimes, it may just require paying more attention to what’s around us, and humbly asking ourselves whether we truly understand it.