The imperative for women to be self-confident is ubiquitous. In the workplace, even as pay and seniority gaps barely shift, women are called on to believe in themselves. They are often encouraged to enrol in leadership and confidence training courses, such as Google’s #IAmRemarkable programme designed to boost the ability of women (and other under-represented groups) to self-promote and speak up about their talents. In the beauty industry, where women and girls are subjected to unrealistic body ideals, brands hire ‘confidence ambassadors’, tasked with making women feel more confident in their appearance. Meanwhile, the fashion industry tells women ‘confidence is the best thing you can wear’. Advertising, notorious for its reliance on sexist, racist, ageist and ableist stereotypes, is being reinvented as ‘femvertising’. There is a proliferating genre of women-oriented self-help that places female self-confidence at its heart, including books such as Sheryl Sandberg’s hit Lean In (2013), The Confidence Code (2014) by Katty Kay and Claire Shipman, and Rachel Hollis’s bestseller Girl, Stop Apologizing (2019). Motivational speakers share tips on how women can develop their self-esteem, and inspirational quotes circulate on social media calling on women to ‘have the courage to stand up for yourself’ and ‘be proud of who you are unapologetically.’

In our research, we take this new ‘common sense’ to task. Our aim is not to argue ‘against’ confidence in some straightforward way. After all, who could possibly be against confidence? Would anyone genuinely want to position themselves against making young women feel more comfortable in their own skins, endowing mothers with self-esteem, or helping older women feel confident in the workplace? Of course not. Moreover, we are ourselves implicated in confidence culture: moved to tears by some of its exhortations, excited by equality and diversity programmes that seem genuinely to celebrate women’s achievements, and often encouraging our female students and colleagues to be more assertive.

Yet precisely because confidence has become such a prominent and unquestioned social good, it demands serious interrogation. What ideas, discourses, images and practices make up the confidence culture? Why has it emerged and proliferated across so many areas of life at this particular moment? And, crucially, what does the contemporary cultural preoccupation with confidence do – both at an individual level for those addressed as needing greater confidence, and on a wider social and political scale? These are the questions we address in our book Confidence Culture (2022). Confidence, we argue, is both culture and cult. It disseminates across multiple domains in culture: in relation to body image, in the workplace, in sex and relationship advice, in parenting, and in development initiatives in the Global South. It is also a cult, in the way it has been placed beyond debate, almost like an article of faith.

The contemporary cultural prominence of confidence is the result of multiple trends and shifts. It is situated in the rise of therapeutic cultures and the way that psychological ideas have come to shape workplaces, schools, the military, the carceral system, parenting and many other spheres – all part of the ongoing remaking of capitalism along more psychological lines. It is underscored, too, by the huge expansion in self-help, particularly that which is directed at women, with the notion that femininity is a ‘problematic object in need of change’. The soft power of lifestyle media adds to this, and social media have become sites of a huge range of aphorisms, affirmations and ‘inspo’ messages, often organised around hashtags such as #MotivationMonday, #WellnessWednesday and #SelfCareSunday.

The cultural resonance of confidence is also closely related to dispositions such as grit, positivity and resilience that have been championed by neoliberal governments. In the face of the withdrawal of the state and the absence of social security and safety nets, individuals – particularly women and people from disadvantaged groups and underserved communities – are increasingly called on to look after themselves, and assume full responsibility for their own wellbeing and safety. It is in this climate, and especially in the context of recession, austerity and the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit women hard, that confidence culture has taken hold. Across different spheres of life, from the workplace to intimate relationships, in consumer culture and policy programmes, women are continuously encouraged to overcome their supposed psychological deficits and so-called self-inflicted injuries by working on themselves and caring for themselves (because no one else will).

Confidence messages not only disproportionately address women. They are also frequently mobilised as an explanatory framework wherever there is talk of gender inequality or injustice. Whatever the problems or injustices faced by women or girls, the implied ‘diagnosis’ offered is often the same – she lacks confidence – to which the proffered solution is to promote female self-confidence. Inequality in the workplace? Women need to lean in and become more confident (check). Eating disorders and poor body image? Girls’ confidence and Love Your Body programmes are the solution (check). Parenting problems? Just be a ‘sorry-not-sorry’ mum and raise confident kids (check). Sex life in a rut? Well, ‘confidence is the new sexy!’ (check). What is striking is not only the similarity of the discourses, programmes and interventions proposed across diverse domains of social life but also the way in which features of an unequal society are systematically (re)framed by the confidence culture as individual psychological problems, requiring us to change women, not the world.

Of course, men are sometimes addressed by messages promoting confidence too, but it is striking to note how differently this operates. The language used is contrasting: men are hailed in terms of performance, success and mastery, often framed in competitive terms. Moreover, confidence interventions targeted at men are usually short-lived and behaviourally focused. For men, being confident is more about focusing on a particular skill or situation.

By contrast, for women becoming confident involves 24/7 labour and vigilance; it features ‘looking inside’ and identifying the ‘blocks’ and ‘internal obstacles’ that are holding them back – what the authors of the bestselling book The Confidence Code describe as women’s self-inflicted wounds. Crucially, confidence in women can never be understood as assured or complete. Rather, it is always a work in progress, lest their confidence tank becomes empty. For women, confidence building requires a total programme of psychological reinvention, not simply a cognitive or behavioural makeover. Most significantly, however, is how confidence is presented as a panacea for gender inequality and injustice, thus framing the causes of social inequality and their solution as women’s responsibility, and theirs alone.

The force and influence of feminist discourse over several decades are partly responsible for the contemporary prominence of female confidence. Indeed, confidence can be seen as part of a progressive political project designed to create a more just society. Without feminism, the inequalities which confidence initiatives seek to tackle would not even be recognised, nor would efforts be expended on improving women’s self-confidence. Yet the versions of feminism deployed in confidence culture are troublingly individualistic, turning away from structural inequalities and wider social injustices to accounts that foreground psychological change rather than social transformation.

Phrases such as ‘sometimes you’re your own worst enemy’ or ‘your lack of confidence is holding you back’ cast the obstacles as if they were simply in women’s heads, rather than the result of a systemic culture that subordinates women and then continuously blames them for their own insecurities. Consequently, confidence culture lets off the hook institutions and structures of contemporary life. In locating the cause of social injustice in a confidence deficit, confidence culture calls for women to undertake intensive work on the self, from changing the way they look, communicate, breathe, and occupy space, to enrolling in never-ending psychological work through practices of gratitude, affirmations, self-friending, and constant self-regulation.

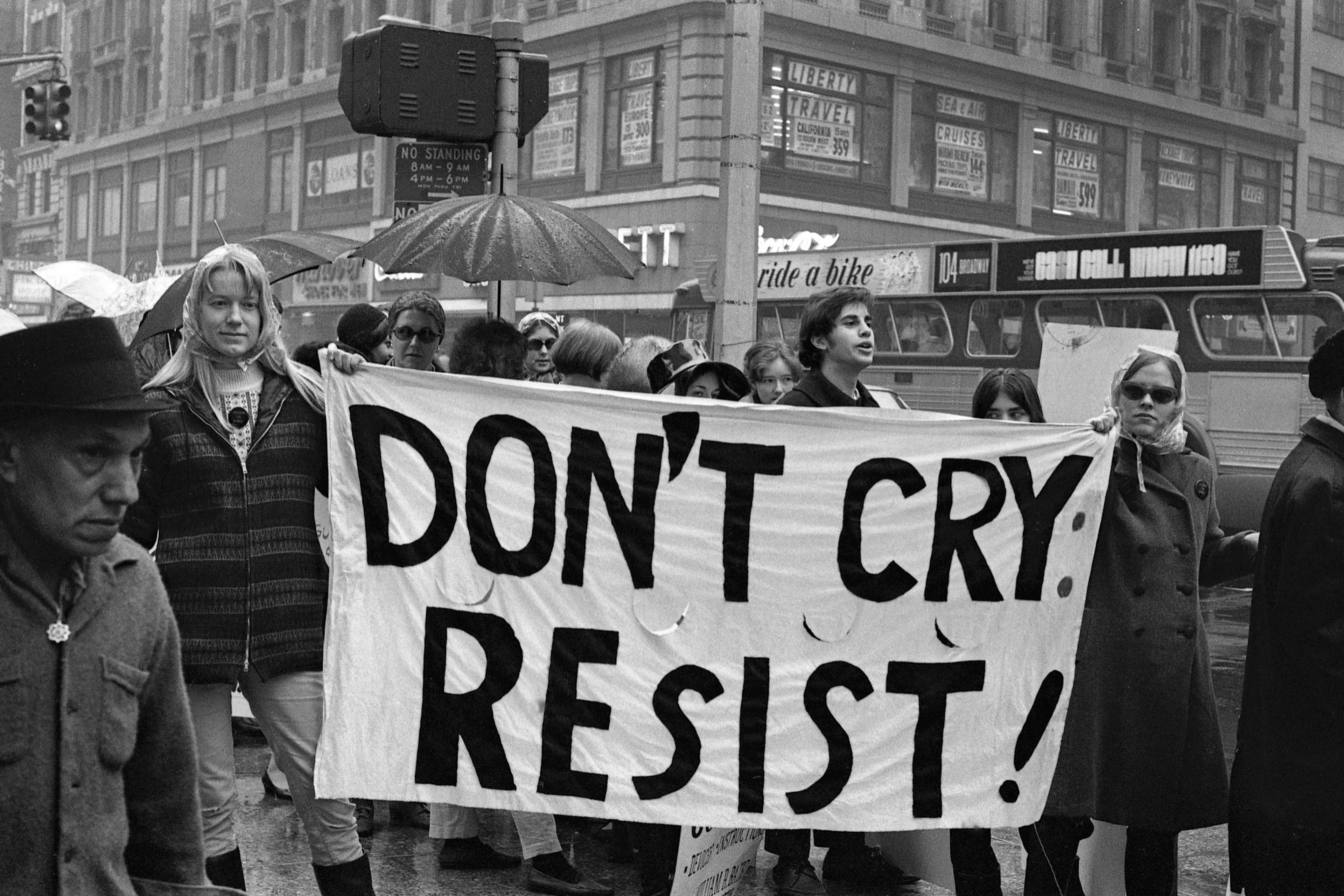

Thus, despite its outwardly progressive aspects, ultimately the confidence cult mislocates the source of and the solution for social injustice in women rather than in the unjust structures and institutions of contemporary capitalism. Its message is: fix the woman, not the world. Rather than focusing energy on individualistic programmes that aim to change women, we need a more productive and structural approach. We need to shift the emphasis from individualised and psychologised imperatives to investing in building a climate of confidence: a physical, economic and cultural environment that supports and reinforces the wellbeing, safety, economic security and power of all women, both as a collective and as individuals.