What happens when we think we know it all? A very instructive answer comes to us from the Middle Ages in the confrontation between Peter Abelard (c1079-1142) and Bernard of Clairvaux (c1090-1153). Most of us are likely more familiar with Abelard from his scandalous love affair with Héloïse (c1098-1164), the brilliant 15-year-old whose uncle hired Abelard as her tutor. Yes, that story turned out exactly as you’d expect: Abelard and Héloïse, star-crossed lovers long before Romeo and Juliet, fall in love but are pulled apart. The uncle’s thugs castrate Abelard, and Héloïse is shut behind a convent’s walls.

But this is not the cautionary tale we tell here. Our concern is with Abelard’s confidence that his scholastic method could help him figure out nearly everything. We hear a boldness, which could well be rash and lead to pride, in Abelard’s scholastic text Sic et Non, or Yes and No (1120). The whole point of his treatise was to walk straight into questions of theology where some commentators said x and others y. Abelard’s goal was to resolve the disagreement and come to a reasonable conclusion. ‘Indeed, by doubting we come to enquiry,’ he wrote about his method and intent in his prologue, ‘by enquiring, we perceive truth.’

Peter Abelard. Courtesy Wikipedia

Bernard of Clairvaux. Courtesy the Prado, Madrid

Abelard’s method made some people nervous because it could work against – or even ignore – humility. One of the most disturbed was Bernard, an early member of the Cistercian order known also today as the Trappists. There is a caricature of Bernard as an enemy of learning. He wasn’t, but what concerned him was an unchecked exploration of knowledge for its own sake or for the glory of the author. Bernard wasn’t anti-intellectual, but he stridently warned that pride could easily take over discussions of topics that should be approached humbly. Was the scholar seeking insight or fame, he asked. Was cleverness outrunning proper limits? Could being inquisitive and speculative lead to trouble for a person’s psyche or soul? Bernard feared so. Abelard disagreed.

The medieval mind had a phrase for this conundrum: learned ignorance. But why would anyone want to be ignorant? Some people think it’s bliss. Charles Darwin noted in the introduction to The Descent of Man (1871) that often people who don’t know much are sure that they do – which is quite dangerous: ‘ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.’ Some people won’t try to learn because they have no desire to be taught. Why? Because they don’t think anyone can tell them anything. That’s hubris, not humility.

The notion of learned ignorance recognises that there’s always something more to learn, which should make even the most accomplished expert humble. If we think we know all there is to know about a topic, we must admit and accept that there will be later developments that can change our minds and fill out the picture all the more. In the early 17th century, Galileo Galilei saw Saturn’s rings and Jupiter’s moons, but in the 1990s the Hubble telescope saw far beyond our solar system. If Galileo declared that he’d seen all there was to be seen, he’d have been a fool.

What is the danger of not being humble and of being sure that we know it all? We can pursue more answers from the past via Al-Ghazālī (c1056-1111), a Persian philosopher and mystic who spent much of his career in what is now Syria, Iraq and Iran. In The Beginning of Guidance, Al-Ghazālī described pride, arrogance and boastfulness as chronic diseases of ‘man’s consideration of himself with the eye of self-glorification and self-importance and his consideration of others with the eye of contempt. The result as regards the tongue is that he says “I…I…”.’ In giving advice, the proud person can be cruel; when he gets advice, he rudely dismisses it. What is Al-Ghazālī’s guidance on how to learn from others? Study with a humble heart and mind. ‘If he is a scholar, you say, “This man has been given what I have not been given and reached what I did not reach, and knows what I am ignorant of; then how shall I be like him?”’

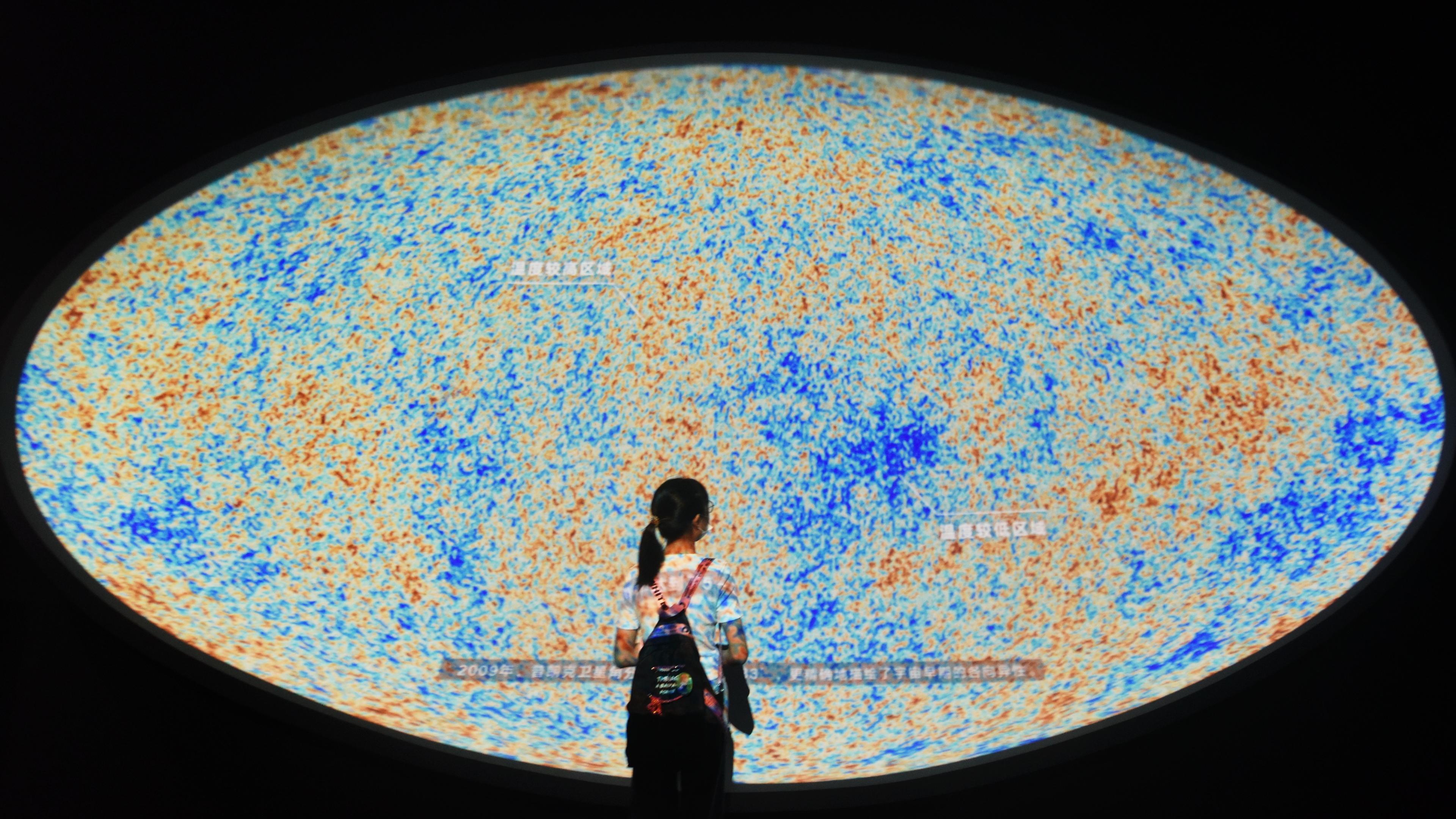

Our understanding of a specific topic is represented by the polygon; full knowledge of that topic is the circle

Thomas Aquinas (c1225-74) split this Gordian knot of knowing and not knowing with his helpful thoughts about pride and humility. Aquinas addressed these topics in several questions in his Summa Theologica within the larger context of virtue and vice, but particularly modesty. He equated moderation with a reproof to zeal, especially when tempering the drive to study with unchecked curiosity. It was Aquinas’s position that humility curbs the notion that we think we can know everything. But he also advises that humility can help us to figure out what we can know using reason, and to understand the stopping point where reason fails.

Pride, on the other hand, pushes your thoughts about yourself and what you know out of proportion and perspective. When it goes way too far, we have hubris, which the ancient Greeks warned against, especially when humans tried to reach up to the gods. As Darwin would note centuries later, Aquinas is concerned that you’re tempted to be overconfident, overblown, and presumptuous: ‘excessive self-confidence is more opposed to humility than lack of confidence is.’ Strutting is dangerous. Aquinas applauds keenly applying an astute mind to a problem but admonishes against thinking that you can ever be a complete expert in that problem. To his credit, he understood this in his own life. Aquinas had a heavenly vision that put him in a stupor and drove him to try to burn all of his writings, which he likened to straw in light of what he’d experienced. He’d seen for himself the benefit of learned ignorance.

To demonstrate this visually, we turn to a German thinker named Nicholas of Cusa (1401-64). In De Docta Ignorantia, or On Learned Ignorance (1440), he offered the image of a polygon drawn inside a circle. Our understanding of a specific topic is represented by the polygon; full knowledge of that topic is the circle. Even if we could enlarge the polygon inside to get as close as possible to the circle that frames it, the polygon would still never be a circle. Our understanding is always finite: we will never know all there is to know about the topic we’re studying. ‘Therefore,’ he writes, ‘it is fitting that we be learned-in-ignorance beyond our understanding, so that (though not grasping the truth precisely as it is) we may at least be led to seeing that there is a precise truth which we cannot now comprehend.’

If you’re not born humble, are you out of luck? The history of humility says we can learn to be humble, or at least a bit humbler, than we are now. We often say that we want our children to grow up confident and resilient. Humility is a virtue that helps with both of those goals if we dare to practise them. Aristotle said that we are what we repeatedly do. We build character with practice that develops habit. We learn by doing. Words are cheap. Actions are hard, but they reveal character. An openness to humility can be cultivated early, starting when our children are young. Little ones have an admirable open-mindedness that our cynicism buries as we age; we adults need to fight that tendency.

Anyone who has quit smoking knows that you can replace a bad habit with a good one. Encountering others with an open mind to our own skills and limitations is instructive. We can practise gratitude for the opinions, experiences and generosity of other people and groups. We can examine our own culture of ranking and labelling people by wondering how people rank and label us. When we see someone else’s talents and skills, are we envious or admiring? It’s fine to be properly proud of our own talents and skills (I can teach a good course) as well as properly humble when understanding our own deficiencies or inabilities in manual things (I can’t change the oil in my car). We can’t fix a flaw that we don’t admit exists.

For the last 20 years of his life, Abelard ping-ponged between teaching and condemnation. At one point, there was supposed to be a debate between Abelard and Bernard, but it turned out Abelard was just expected to stand up and be denounced. That’s a reminder that Bernard, who was a bit old-fashioned and even stuffy, could also be fairly accused of thinking he knew best. Still, the two men were personally reconciled in Abelard’s final months, which speaks to the possibility that, even after many years of disagreeing, two people with very different opinions decided they didn’t have to be disagreeable to each other. Each had been a bit humbled. Then and now, humility is a virtue worth recovering.