The message from a century ago resonates loud and clear: emotions matter in international history. Accepting to serve as president of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, the French prime minister Georges Clemenceau insisted that the success of any peace treaty depended on the mutual feelings of those who signed it, declaring: ‘We have come here as friends. We must pass through that door as brothers.’

Clemenceau wasn’t alone in making this point. The United States president Woodrow Wilson blamed war on nations’ ‘passions’ run amok, and saw the League of Nations as a means to control and channel them in positive ways. The Belgian representative Paul Hymans, who was named president at the League’s first assembly, explained that ‘our goal is to establish among independent states frequent and amicable contacts, rapprochements that will spurt out currents of affinity and sympathy.’ For Hymans, the League responded to ‘a sentiment … of justice, harmony, and peace’. Indeed, to many of its proponents, the League’s emotional value constituted its most important contribution as it addressed people’s deepest, most authentic core: their feelings. And, managed correctly, these feelings could be transferred from individuals to nations, and from the personal to the political realm.

One should not dismiss these appeals to emotions as idle chatter. In fact, numerous individuals, institutions and governments implemented policies aimed at putting rhetoric into practice. They organised an unprecedented number of international encounters, devoting great energy to managing the emotions expressed and engendered on these occasions. Concerns about feelings dominated these events, shaping what international cooperation was in this period, and also influencing how people remembered it in later decades.

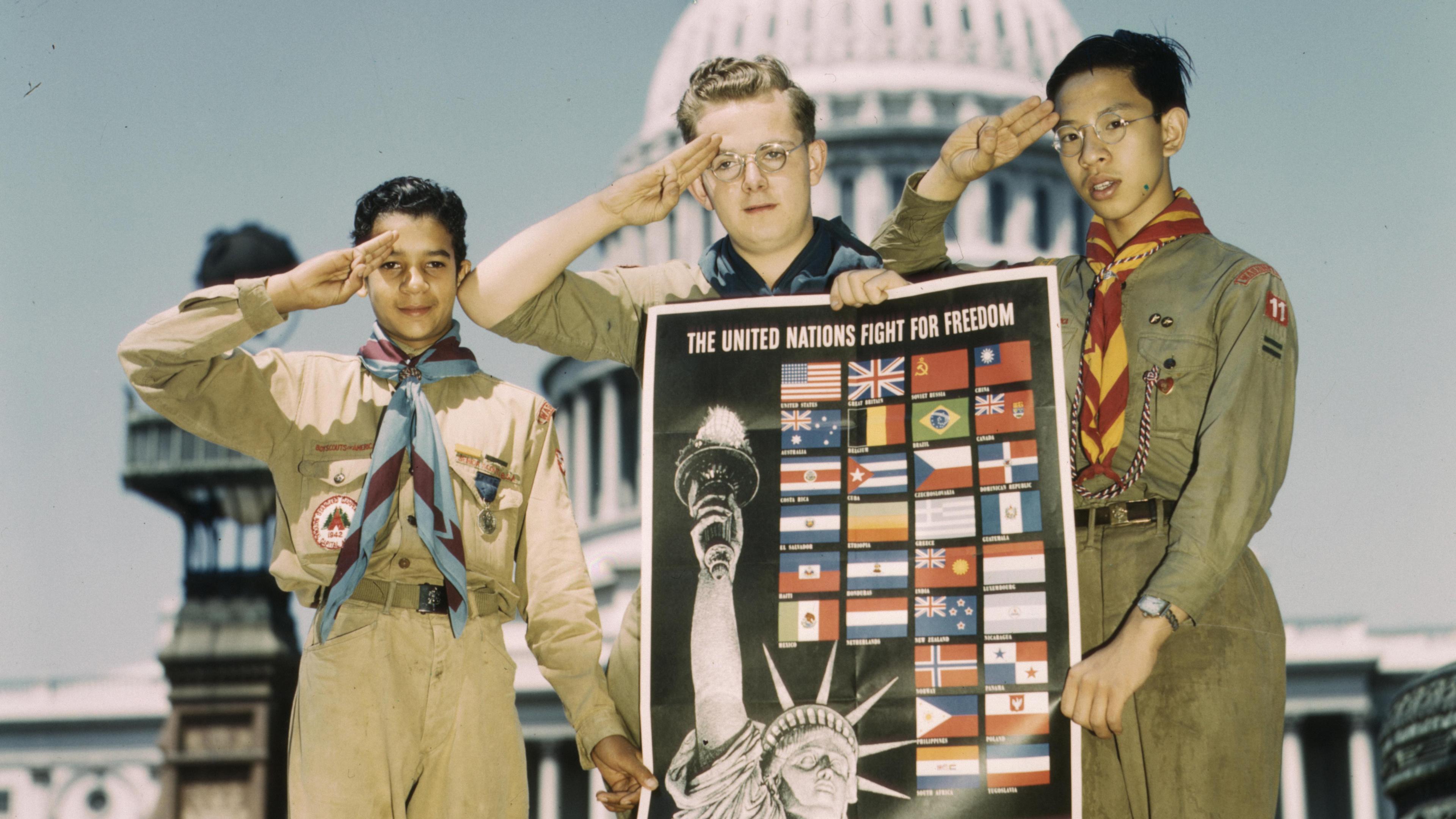

This emotional surge originated from the League of Nations itself, especially its technical sections. Since the beginning, the League was involved in ‘activities in connection with the promotion of functional cooperation’. These included committees and organisations responsible for communications and transit, economic and financial cooperation, intellectual cooperation, social questions, legal work and health. After the Second World War, some of these grew into separate bodies – the World Health Organization, for instance. Many of these committees and organisations encouraged initiatives aimed at engendering international amity. In the field of education alone, many study-abroad and exchange programmes sprouted up as a result.

The people who ran these programmes believed that, even in the most conducive environment, desirable emotions would not develop spontaneously, but instead needed to be actively stimulated and carefully managed. A 1933 publication by the Institute for Intellectual Cooperation in Paris stated the challenge: successful examples of international cooperation featured accommodation, courses and excursions specifically designed ‘to foster in the students a camaraderie that leads them to live in common without distinction of nationality’. The goal was to ‘incline their spirits in the way of peace among peoples’. Every detail had to be taken into account for this to happen: for instance, during sporting activities, teams had to be mixed in terms of nationality and economic background to avoid resentments. Meanwhile, accommodation was to be organised by placing together people of different nationalities and classes in the same social condition. This measure was intended to make them feel at ease and to foster amicable interactions.

Attempts at emotional management spanned beyond Geneva and the League of Nations. In 1932, a group of alpinists from different countries formed the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation (also known as the UIAA), adopting much of the League’s rhetoric and organising international congresses. The UIAA worked to ensure that delegates of different provenance sat together, shared food, music and entertainment in an atmosphere of amicable cooperation. In this endeavour, sport and leisure could not be separated from the political objective of fostering peace and international collaboration, as well as the emotions that made them possible. Printed material specified the nationality of each participant, thus reaffirming the UIAA’s support of the League’s principle of national self-determination. In-person gatherings began with an internationalist ritual where individuals would introduce themselves first in their own language and then either in English or in French – the League’s official tongues. Carefully conceived groups and seating arrangements avoided national cliques and ensured that people would mix. Later accounts emphasised the success and significance of this international mingling.

Similarly, international sanatoria for the treatment of tuberculosis – a widespread disease that affected millions across borders – were organised in such a way that patients from various countries would become friends. From schedules to décor, from clothing to food, everything was designed to foster international friendship. Publicity and memoirs written by visitors and patients reinforced the notion that this experiment worked. Let’s take for instance the International University Sanatorium of Leysin in Switzerland, where students and faculty with tuberculosis continued academic work while undergoing their treatments. Facing a shared challenge, they would experience friendly interaction, communicate its benefit to others, and thus contribute to promoting peace.

The Swiss professor Marcel du Pasquier commented on how each guest was introduced to a patient who spoke a different language, yet conversation would nonetheless ensue. At mealtimes, ‘a German student next to a Polish one: they are a pair of friends. The Swiss cantons fraternise; medicine and law share bread and cheese,’ he noted in one of his writings. Another visitor, the Swiss professor of literature Giuseppe Zoppi, described his encounter with two students: the first, who’d had surgery the day before, had already returned to his studies; the other helped him. Zoppi pointed out how in their country of origin ‘they had never met, while here they are like brothers’.

To be sure, not all visitors left Leysin uplifted. In his book Les heures de silence (1934) or ‘The Hours of Silence’, the Swiss internationalist and essayist Robert de Traz wrote about the sadness and despair he encountered at Leysin. However, in the same work, he also described patients discussing theories for international rapprochement and mentioned how they showed the flags of their countries of origin while finding themselves united across national borders by the common experience of disease. To him, the fact that this was a small establishment mattered less than the greatness of its purpose of promoting, at once, health and peace. Declaring the university sanatorium of Leysin an extension of the League on the Alps and a space for amicable exchange effectively made it one, guiding the norms and behaviours of those who populated it to the point that its dominant representation, feeling and memory became more important than its reality.

Still today, in times of difficulty and tensions, political leaders resort to emotional language – such as references to a ‘European family’ – to affirm and draw connections among nations. The European Union has built itself through schemes such as the Erasmus exchange programme, established in 1987 to foster the formation of a European identity and of ‘good Europeans’ who share emotional bonds across borders. Governmental and nongovernmental bodies operate along the same lines when staging initiatives ranging from educational programmes to corporate team-building activities. Even the criticisms by those who don’t support internationalism – such as extreme-nationalist movements – might be best understood as the latest chapter of the longer history of emotions. Political alliances or movements are built on shared feelings. Understanding the history of emotions across borders is therefore a powerful tool for examining their uses and misuses in the past, and also for considering the role of feeling in our global present and future.