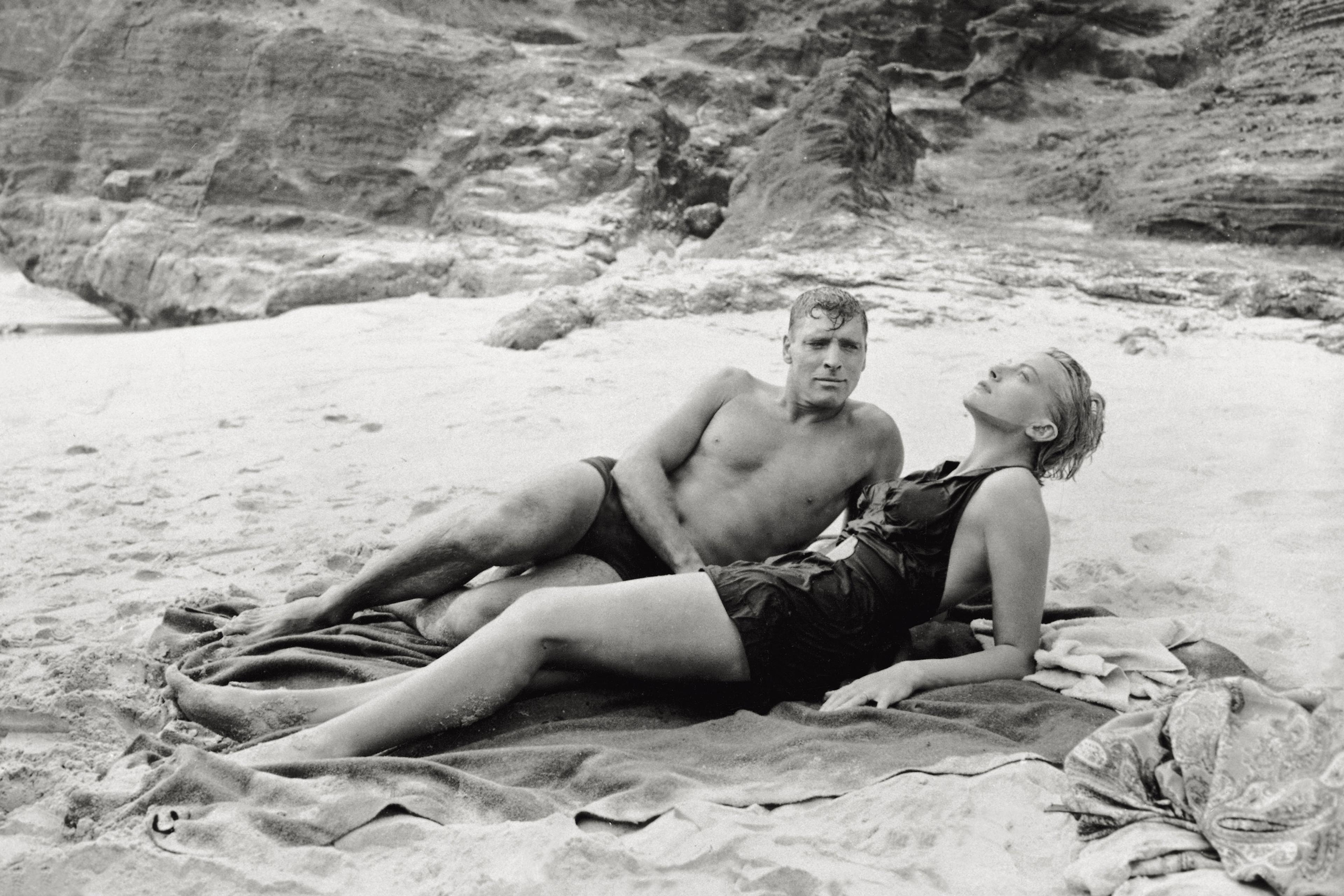

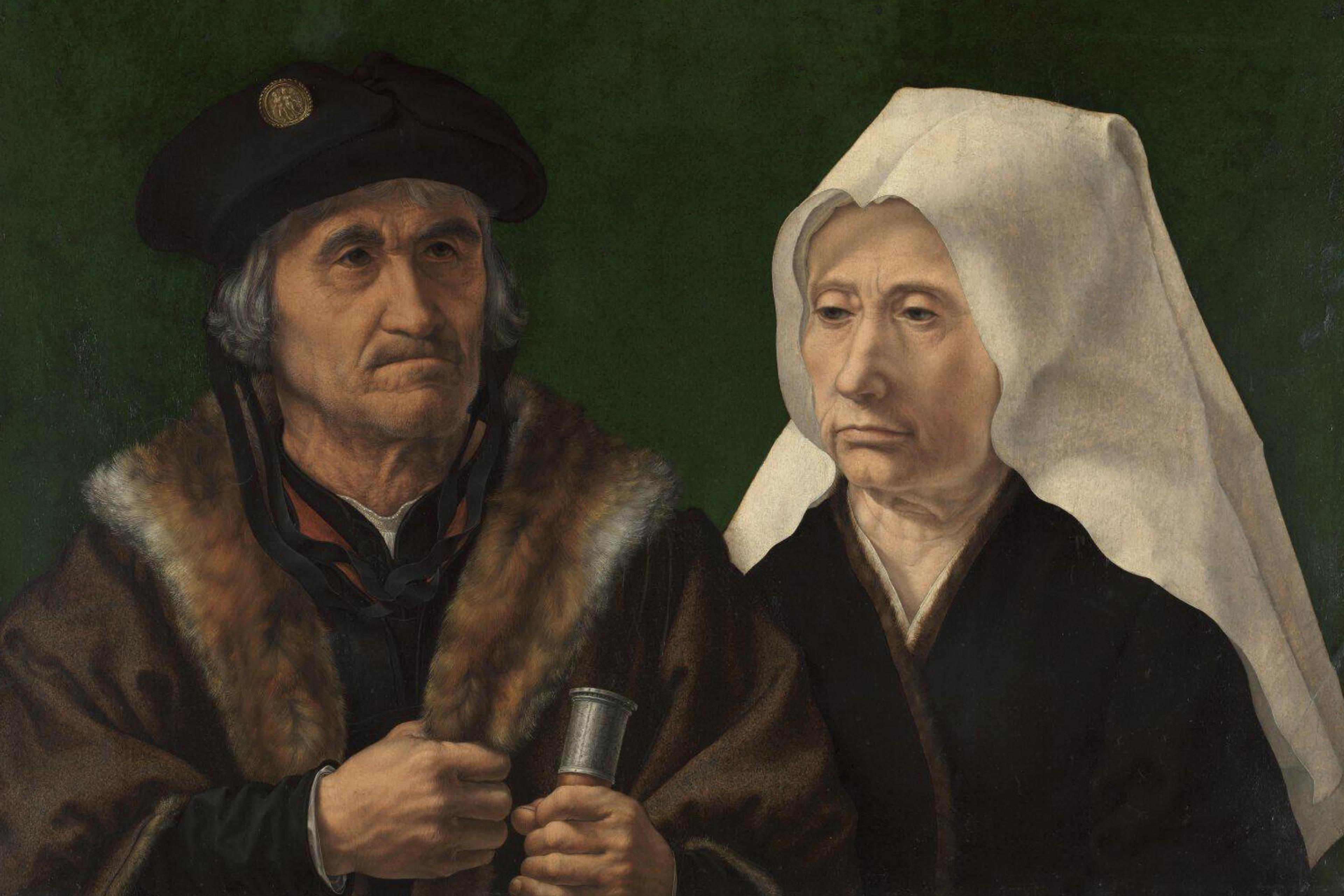

When there is domestic trouble, we might think of love as part of the answer. But what if love is part of the problem? As we know from research in history and sociology, family life in Western societies in the past was dominated by a patriarchal and heteronormative understanding of marriage, in which love was largely on the sidelines. Only heterosexual partnerships were socially sanctioned, and marriages had more of a civic and religious foundation than a romantic one. Marriage was thought to unite a man and a woman’s wills, with the woman’s being largely subsumed into the man’s.

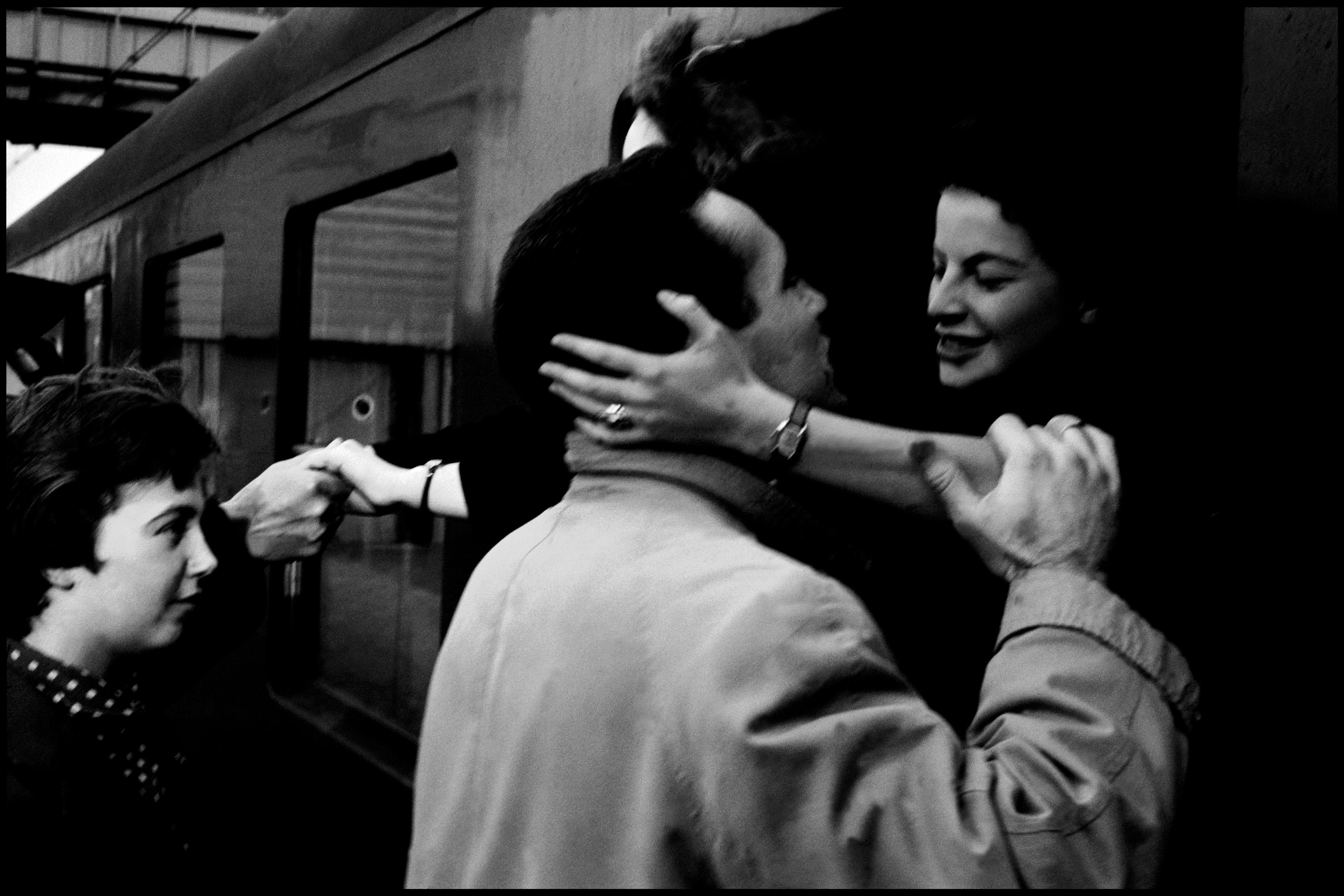

By contrast, our contemporary understandings of family life are dominated by love. For many people, falling in love determines whom we should connect with. Staying in love is seen as the glue that keeps us together, and the death of love is seen as grounds for divorce.

The centrality of love in domestic life has some wonderful aspects, reminding us of the importance of care and warmth in our daily interactions. But this centrality also has a distinctly dangerous and dark side.

Essentially, the problem arises from the way we tend to see love in terms of sharing and caring: we should bond together and look out for the other person. Our modern rhetoric of love is very much an all-in, maximising kind of thing: true love, we say, knows no limits and conquers all. But thinking about fairness not only requires seeing ourselves as distinct from others, it can also mean looking out for yourself first. This makes fairness and love seem incompatible, and impedes the honest conversations necessary to household justice.

From a philosophical point of view, the idea of love as caring and sharing finds expression in two different theories. One, the ‘union theory’, says that love creates a melding of the people in love, to form a new entity, a ‘we’. Another, the ‘concern theory’, maintains that the people remain distinct, but says that love requires taking on the beloved person’s needs and interests as your own.

The appeal of these theories is obvious. Imagine that the person you love gets sick. The ‘we’ theory says that their burdens are your burdens: since pains are shared, they bear less heavily on each person, afflicting them equally. The concern theory says that you should prioritise their wellbeing and act in ways that will make them better off when you can.

But trouble lurks behind this Hallmark veneer. The challenge arises in cases where what is good for one person conflicts with what is good for another. For example, imagine that your spouse gets a great job opportunity in a new city, far from family and friends, and far from activities and people central to your happiness. It might be that what is best for your spouse is to accept the offer, and what is best for you is for them to reject it.

Union and concern theories of love lead to bad reasoning in these contexts. Taken at face value, the union theory seems to lead to the conclusion that what is good for your spouse is good for you and vice versa, obscuring the possibility that there is a genuine conflict. If you raised an objection to moving, your spouse could accuse you of being selfish and unloving, refusing to fully integrate your selfhood with theirs. The concern theory seems to say that you should prioritise and adopt as your own your spouse’s desires and interests. In this case, not only would favouring your own position be selfish but, even if you lovingly decided to go along with the plan, your spouse could deny that you’d made any sacrifice for them: since you love your spouse, it’s what you want too!

Essentially, the problem is that from both perspectives, love seems at odds with individuality and self-interest. That’s great for a romantic, fairytale vision of love. But it doesn’t work well for practical cohabiting, childrearing and shared decision-making. In these contexts, we experience frequent conflicts of interests. Maybe everyone wants to eat, but everyone prefers that someone else cook or wash the dishes. Maybe both parents want their kids to get lots of attention during the day, but both also have jobs and other projects. It’s impossible to confront these conflicts openly if standing up for one’s own position is seen as antithetical to love. In heterosexual couples, the problem also takes on a gendered aspect because social norms encourage women to adopt more caring attitudes in the first place.

We have underappreciated the degree to which our understanding of love derives from the metaphor of the patriarchal marriage of the past. In that case, marriage was a ‘union’. But this union was essentially achieved at the expense of women being subordinate to men. The old metaphors no longer work for us.

A better way to think about what we owe to one another in family life would not only leave aside unity and all its problems, it would shun obsession with ‘all-in’, limitless, love-conquers-all ways of thinking altogether. Instead of ‘conquering’, we should think more in terms of ‘balancing’: finding a way to look out for the other person while also looking out for yourself.

The metaphor of balancing means incorporating different considerations into a decision that respects the significance and weightiness of various, possibly conflicting, factors. It also requires thinking about how decisions are affecting each person, and a certain amount of shared deliberation. For example, where one person wants to move and the other wants to stay, the deliberation should take into account the ways in which the decision will affect each person. If one person gets their way and the other suffers on this occasion, then together they should aim for decisions that balance that out over time, so that the other person gets what they want and need at another time.

Obviously, balancing is subjective. To balance we must make judgments about how much things matter, what should or can be given up, how much hurt is too much. These are matters about which people have disagreements – sometimes huge, relationship-ending disagreements. But the metaphor of balancing is apt for understanding an activity we already do in such cases: we try to impress upon our loved ones a sense of how important things are to us, and why we care, so that they’ll come to share our sense of what matters, how much it matters, and what it would be best to do next.

This kind of deliberation has little to do with unity or with limitless concern. In fact, these would actively get in the way, by obscuring the different people’s needs and interests. Instead, it requires us to see ourselves as individuals and to face squarely the ways in which our interests diverge. If the person who wanted to stay kept valiantly insisting that they wanted to move, because it’s what they thought their spouse wanted, a frank and honest conversation about the mutual impacts of the decision would be impossible.

Crucially, balancing and deliberation aren’t somehow special to love or family life. They’re good ways to approach any mutual shared projects and parts of life. They’re how we engage in friendships and other situations where we’re trying to accomplish something together. Using balancing for family life means letting go of the idea that love creates a unique and special bond that applies only within the domestic sphere. Instead, our relationships fall along a continuum of caring.

If equality and fairness require individuality and deliberation rather than the all-in unity of love, it’s worth asking why metaphors such as unity persist. One possibility is that, especially in modern capitalist societies, we dream of a home that is a sanctuary from the negotiation and bargaining of everyday public life. Managing conflicting interests and individuals who want and need different things is challenging and, in our social structures, often requires pushing yourself forward, fighting for what you want and need. With love as unity or caring concern, it might appear that family life becomes a conflict-free zone, a place where you don’t have to fight for yourself. You’ve got others looking out for you.

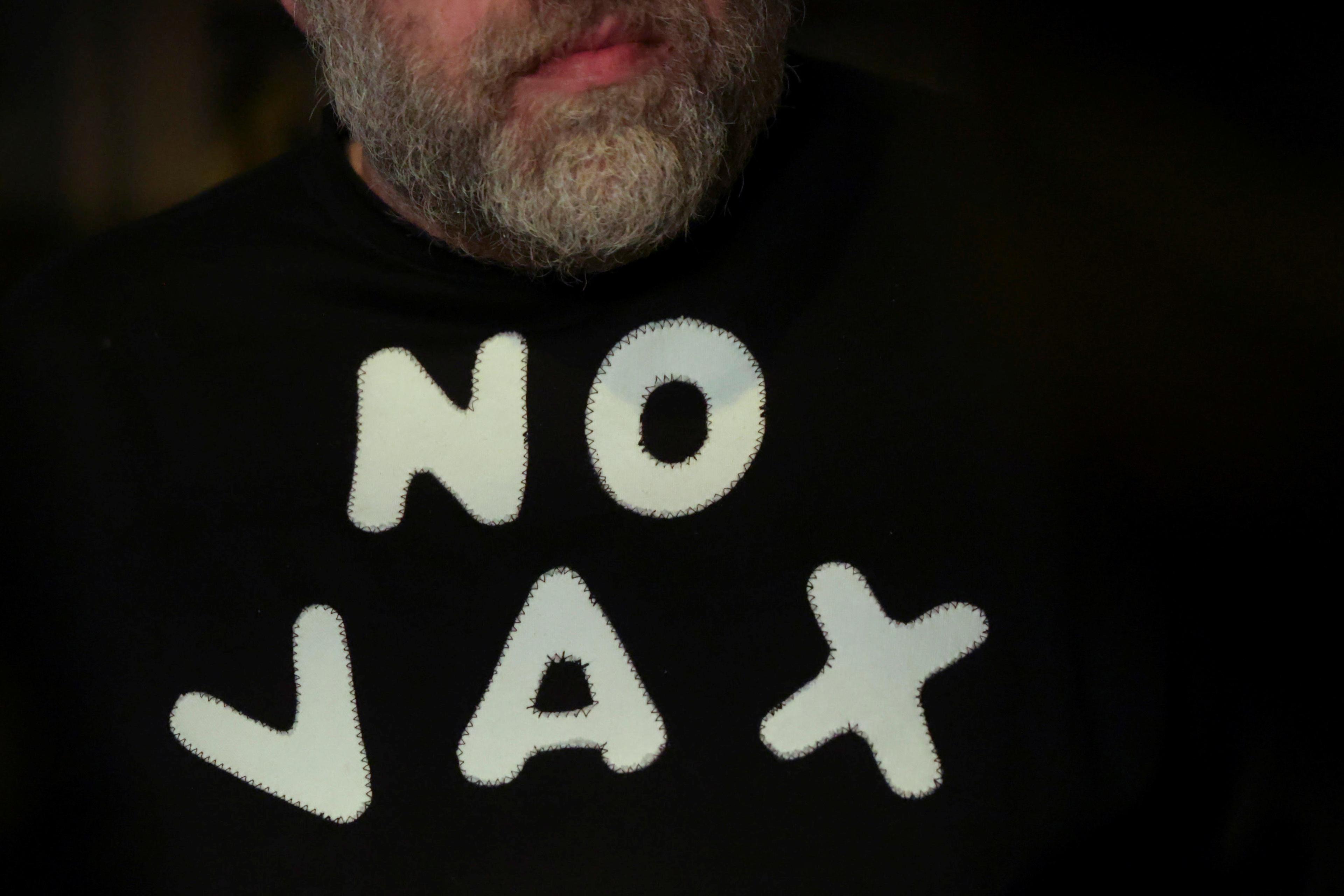

The challenges of unity and concern delineated here suggest that, in the past, this dream was purchased at the cost of patriarchal sexism, in which unity is achieved through women’s interests being sublimated, and that it is impossible to square with fairness and equality. The social norms associated with this frame are difficult to set aside, which is one reason why the COVID-19 lockdowns have seen an expansion in traditional gender roles and a rise in gender inequalities: even when working from home, women have been taking on more tasks associated with caring for children, homeschooling, housecleaning, and food preparation. But seeing love as unity or caring doesn’t help us frame the problem, and in fact contributes to it.

Ultimately, we must confront the possibility that love is not a special relation that structures our interactions with a tiny number of people. The caring we feel for our family members is not different in kind from what we ought to bring to all our social interactions.

In any case, the challenges of domestic life are best understood when we see them not through unity but rather through partnership. So, when it’s time for affection and fun, sure, go all in with love! But when it’s time to decide who washes the dishes, don’t let love get in your way.