My earliest memory of going to the polls on Election Day is from long before I was eligible to vote. My mom picked me up from school and we headed to the city auditorium, her precinct polling place. I had been there before to watch a friend’s dance recital, but the room had been transformed. Instead of rows of folding chairs on the hardwood floor, there were now several blue-curtained voting booths, a few people sitting behind folding tables, and two lines of people in front of them. I remember being impressed as the poll worker flipped through the pages of a heavy, overfull binder, then turned it around to show my mom her name and get her signature. I remember asking my mom if I could mark her ballot. When she said no, I remember thinking that I could not wait until I was old enough to vote.

At that age, I had only the vaguest idea of what all of it was for. I knew nothing about the candidates or the offices to be filled. But all my senses told me that something special was happening; I had witnessed a ritual of self-government that I longed to be part of.

This experience is becoming less typical in the United States, where I live. In 2020, around two-thirds of votes were cast prior to Election Day, most via mail-in voting. The widespread uptake of mail-in voting that year accelerated an existing trend. Over the past few decades, fewer and fewer ballots have been cast at precinct polling places on Election Day, more and more via mail, early voting, or other methods of convenience voting. The US is something of an outlier, but other democracies have also seen increased interest in postal voting, and it has been common in Switzerland for decades.

To the extent that there has been public debate about this shift, it has largely centred on questions related to security and accessibility. While these qualities are essential, they do not exhaust the considerations we should use to assess election administration. Elections are not merely information-gathering exercises. They also shape citizens’ attitudes toward democracy and their role within it. And popular elections structure the political environment in which interest groups and social movements organise and mobilise for collective action. For these functions, the experience of voting and the optics of elections matter a great deal.

I argue that three key features define the democratic practice of popular voting. First, vote-counting procedures exhibit formal equality: they weigh votes equally regardless of who casts them. Second, prominent elections garner uniquely widespread participation. For example, more than 150 million Americans cast a vote in the 2020 federal elections; compare this with the roughly 100 million US residents who watched the Super Bowl that year. One of the United Kingdom’s biggest television events of recent years, Queen Elizabeth II’s funeral, garnered around 30 million UK viewers. Meanwhile, approximately 32 million people voted in the 2019 UK general election. In today’s democracies, people expect the majority of their fellow citizens to vote, and wonder what has gone wrong when they don’t.

Third and finally, occasions for voting are momentous. I mean this in two senses: they are time-bound, occurring in a defined political moment; and they are attention-grabbing, disrupting our normal routines. At the same time, though, these momentous occasions recur regularly. They create a rhythm to political life in which the ordinary, delegated and diffuse business of politics is punctuated by extraordinary moments of mass participation. Rituals of voting, such as congregating at a local polling place, reinforce the momentousness of the occasion for those who participate in and witness it.

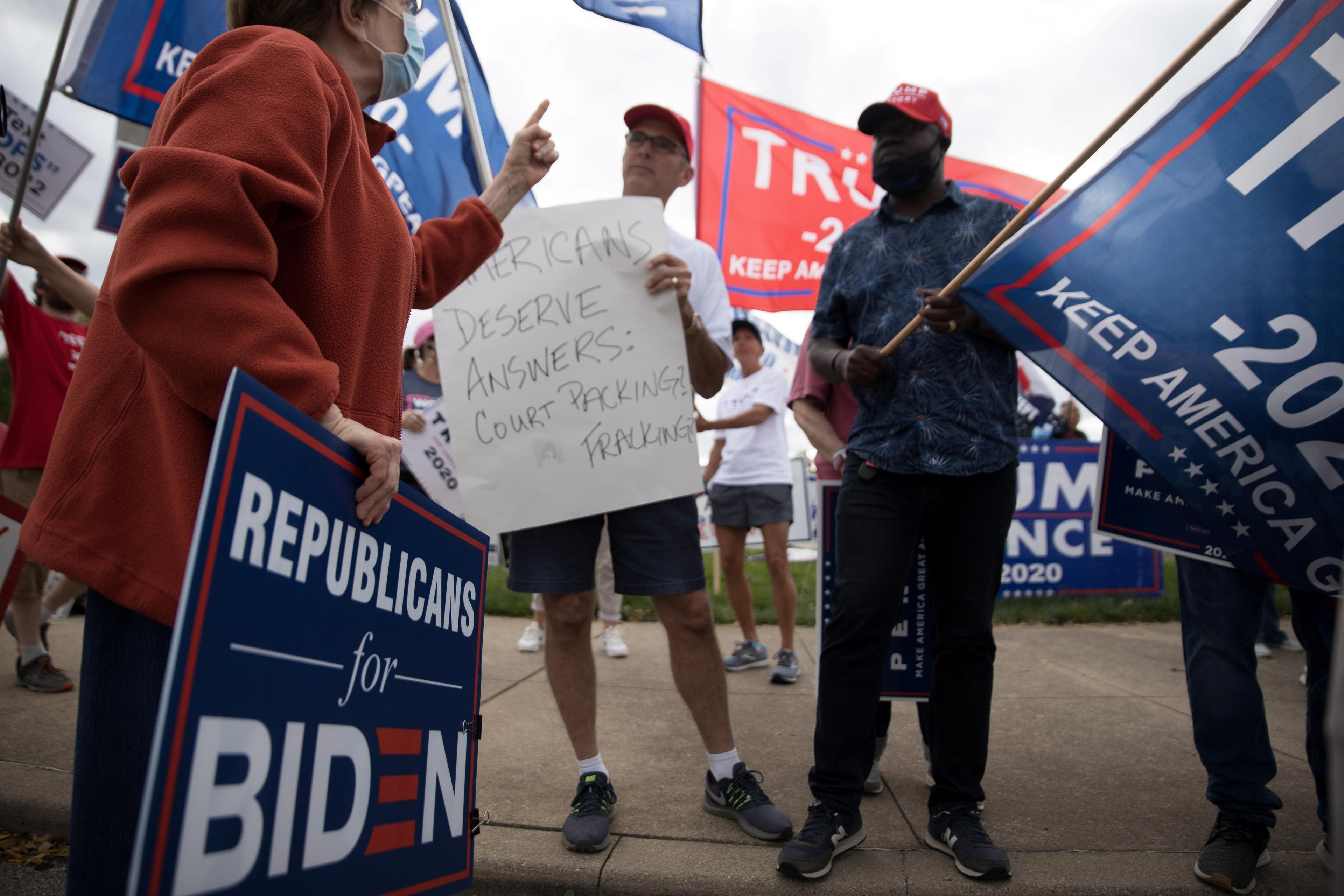

Together these features constitute a practice that manages to make multiple democratic values salient at the same time. The values of individual dignity, political equality, and large-scale collective action – which are often felt to be in tension with one another – are all on display at election time. The iconography of elections juxtaposes headlines about how ‘millions of voters head to the polls’ with images of private voting booths and election judges scrutinising ballots to ensure each one is counted properly. The confluence of democratic values helps citizens to appreciate their role in a democracy. A single vote is extremely unlikely to tip the outcome of an election – and that’s kind of the point. Democracy is always something that we do with others. At the same time, though, individual votes do matter. Dissent is registered and measured, and each vote remains a discrete unit, to be counted and recounted if necessary.

The conjunction of equal counting of voting, mass participation and the attention-grabbing character of elections also means that voting offers a unique opportunity for the community and for individual citizens to express their own commitment to democratic values. The political theorist Dennis F Thompson has argued that, when people go to the polls en masse, ‘visibly and publicly participating in the same way in a common experience of civic engagement, they demonstrate their willingness to contribute on equal terms to the democratic process’.

Some readers might be inclined to dismiss the value of these images and expressions as abstract and immaterial. But that would be a mistake. We humans are embodied, sensory creatures, and our environment affects how we think and feel and behave. Many people feel calmer when surrounded by nature, or run faster when listening to upbeat music. This kind of environmental sensitivity applies to politics, too. Research in which subjects are asked to keep ‘election diaries’ shows how encounters with various stimuli – from campaign material to the voting booth to election night news coverage – can affect what they think about and how they feel. For example, as the political scientists Michael Bruter and Sarah Harrison have found, while excessive waiting at the polls can be irritating, moderately long lines can make the polling place seem like ‘the place to be’, inspiring pride and enthusiasm.

It stands to reason that environmental cues can also affect how people think and feel about the values associated with voting. Lining up at a polling place with others reminds us that participating in democracy is a shared activity, one that connects us even to strangers who might disagree with us. On the other hand, entering the privacy of the voting booth reminds us that our own individual, independent voice matters. Because the modern practice of popular voting connects the abstract idea of democracy to concrete, embodied and sensory experiences, it can play a vital role in the process of political socialisation, helping citizens to develop and consolidate the attitudes that a healthy democracy needs.

The momentousness of major elections makes it easier to become and remain an engaged citizen. In the context of politics, as in other areas of life, disengagement, inattentiveness and inactivity have a kind of inertia. But because elections are momentous – both time-bound and unusual – they can disrupt that inertia and serve as focal points for citizens to enter (or re-enter) political life. At the same time, the fact that voting occasions recur more-or-less regularly helps ensure that citizens perform and practise their political agency, and that they have regular opportunities to experience an infusion of political efficacy.

The environment around elections and its effect on individual psychology also shapes the incentives and opportunities of political entrepreneurs, creating a larger and more attentive audience for political messaging. And because they create widely recognised focal points, elections can enable groups to coordinate more effectively for collective action. How well these functions are fulfilled, though, depends on what the experience of voting and of election season is like.

When, where, how and with whom we vote can determine the extent to which the previously mentioned democratic values are made salient to us, whether we experience voting as something momentous or mundane, whether we associate the act of voting today with past or future experiences, and whether voting leaves us feeling empowered and energised or exhausted and anxious about political participation. The structure of the campaign and voting periods also affects whether and how political energy builds around an election, whether voting is likely to be a topic of conversation, and how potential future voters perceive the significance of the moment.

We should not be trapped into thinking that voting must resemble a Norman Rockwell painting, or the scene I witnessed as a child. My ‘traditional’ US Election Day experience is itself a stark departure from the highly social and chaotic Election Day of the 19th-century US, and it is hardly representative of democracies around the globe. But a concern for how policies affect the social environment around elections and the experience of voting should play a bigger role in debates about election administration.

It may well be true that the increased accessibility that convenience voting affords is worth the tradeoff in terms of an altered voting experience. But even as voting changes, we can still look for ways to reinforce its momentousness and to maintain some of the shared social experience. An election day holiday, already established in some democracies, not only reduces the opportunity cost of voting for some workers, but also conveys a sense of celebration around the occasion. Same-day registration allows citizens to decide to become voters when energy and excitement are at their peak. Countries could even establish an Election Week, offering voters more flexibility than a single day, while still encouraging the perception of the voting period as a singular moment in which people show up together to participate in democracy. Or, counterintuitively perhaps, it might be determined that universal vote-by-mail could do more to preserve the experience of voting as a shared activity than does a regime that offers a long menu of choices for how to vote.

Businesses, schools and other organisations can also reinforce the momentousness of elections by giving workers and students time off to vote, campaign or volunteer as poll workers, and by organising related events and celebrations. And families, of course, can establish their own new rituals around voting. On California’s most recent Election Day, my young son and I rode our bikes together to the nearest voting centre, where he helped me push my ballot into the box. We greeted poll workers, who gave each of us an ‘I voted’ sticker. We all shared a cheer for democracy. My son and I took a selfie with our stickers. Then I dropped him off at preschool, where he told anyone who would listen about how it was a special day.