When I was a child, I was introduced to contemplative practices that changed my life. Starting in the fourth grade, I regularly walked to my grandmother’s house after school. I vividly recall walking along the streets of that neighbourhood, watching squirrels scurry up and down giant pine trees. When I arrived at her house, my grandmother greeted me at the side door and the two of us sat at her kitchen table to enjoy a snack and glass of juice. After small talk about my day, we went upstairs into the ‘blue room’, named because it was painted pale azure, where I laid down. Surrounded by walls of clear daytime sky, she guided me to close my eyes, rest my body, and enter new imaginal worlds.

Over time, drawing from her years of personal practice, she taught me how to calm my body with my breath, focus my attention on a chosen image or sensation, and mobilise my imagination. Forty years later, my appreciation for these fundamental life skills runs deep and, as a researcher, I seek to understand how contemplative practices such as these work so that others can derive their rewards too.

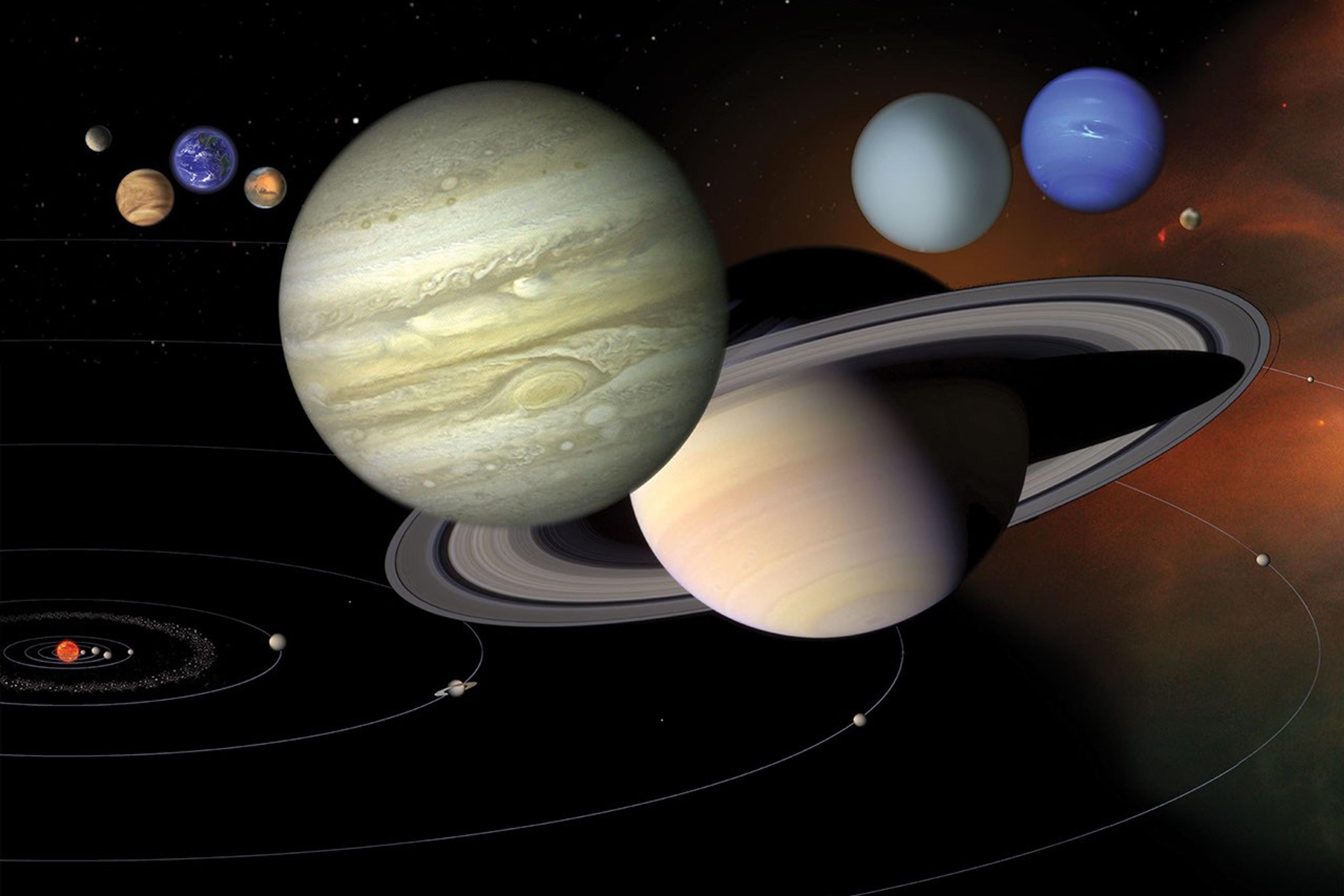

Contemplation, in this sense, refers to a diverse suite of practices and emergent experiences born from the capacity of the human mind to know itself – a feature shared with a few animals, including chimpanzees, bottlenose dolphins and magpies – but, more so, from the mind’s ability to transform itself. Contemplative practices harness this capacity to transform and enhance individuals, communities and lived worlds (including social, cultural and ecological worlds). Across times and cultures, humans have devised a capacious repertoire of practices used to free the self from its felt confines, improve wellbeing, and access new knowledge about being human.

Contemplation is popularly associated with mindfulness and yoga, but it’s a big umbrella that covers many other practices, including techniques to cultivate prosocial emotions (such as compassion), to use the imagination to shape perceptions, to appraise and analyse critical topics, to contextualise the self within broader contexts, and to push the body and mind to total exaltation. By refining skills such as attentional balance, emotional regulation, empathic response, perspective-taking and bodily awareness, practices of contemplation help us navigate and modulate the human experience.

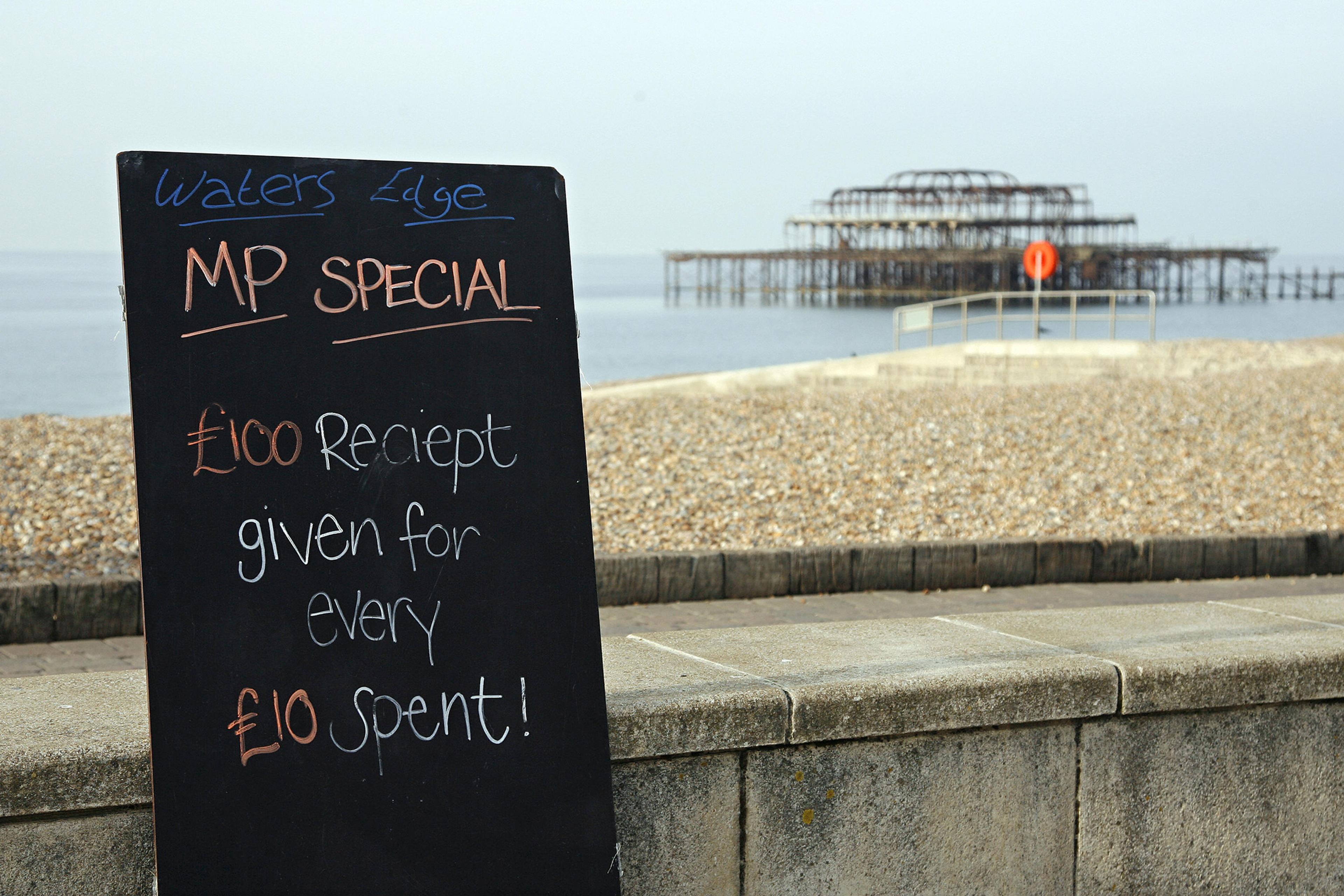

Historically, practices of contemplation were inextricable from the rest of life, including its cultural, philosophical, cosmological and religious dimensions. But since at least the 16th century in the West, due to the systematic rupture with traditions of contemplation, cultural attitudes towards contemplation have gotten skewed. It has consequently been marginalised in many societies, and people have grown estranged from it. To be estranged from contemplation means to no longer recognise your ability to apply specific practices designed to transform and enhance your life – the ability to which my grandmother opened my eyes.

Is there a way to reacquaint people with contemplative practices on a wider scale? To give the gift that I received at a young age? I believe that the domains of arts and sports offer helpful analogues for thinking about how to make contemplation more accessible, and why such practices and experiences are valuable.

As with the skills a person learns through contemplative practices, the skills one learns in arts or sports are applicable to more than just the practices themselves. To learn an art is to cultivate skill sets that include not only technical skills, such as drawing, painting, acting or playing an instrument, but also resources such as adaptability, imagination, criticality, stylisation and attention to detail. Similarly, the competencies that we develop in playing a sport are not limited to the technical motor skills of shooting a basketball, riding a bike, swimming or running laps, or striking a ball for maximum impact, but also focus, spatial awareness, strategic thinking, teamwork, leadership and communication.

Arts and sports, in their own ways, are bedrocks of modern global culture. Children around the world grow up learning various arts and sports from school or community leagues. By the time most of us are teenagers, we have learned how to play the piano or paint a landscape or kick a soccer ball or swim the breaststroke. Though most children will never perform in Carnegie Hall or play in a World Cup, we teach our children arts and sports because we want them to learn valuable life skills and reap the social and psychological benefits.

Parents and educators know that learning an art or sport cultivates certain skills and that, if a child spends the time and effort practising, these skills will enrich their life. The aim is not simply to make them better artists or athletes, but better humans. For instance, sharpening complex dance routines can equip a dancer with competencies of attentional focus, grit and confidence that they go on to express in non-dance contexts. I’ve seen this kind of translational impact as a basketball coach, watching my daughter and her teammates hone their ability to listen, communicate and assert themselves over the course of a season. Though it’s anecdotal, I attribute this to regular practices and games – wherein we’ve emphasised things like consistent communication (eg, making eye contact while passing the ball, calling each other’s names when switching on defence) and the need to be fearless against opponents who were physically more imposing.

Contemplative life skills are also transferable, and because there is such an incredible diversity of contemplative practices, a practitioner can learn diverse skills. For instance, a classic practice is to continually focus attention on the inhalation and exhalation of the breath, and every time the mind strays from the breath, the practitioner reorients their focus. Over time, this strengthens the acuity of selective attention. To take another example, a practitioner might imagine social situations in which they simulate how they behave, which words they choose to speak, and how they empathically respond to others. This perspective-shifting practice would increase their intersubjective awareness in real-life social situations. Or, a person might hike to a waterfall where they sit and listen to its rushing water sounds. This immersive sensorial practice would deepen their listening skills.

The cultivation of such skills – selective attention, intersubjective awareness, listening – can be applied to day-to-day situations to bring benefits in other areas of life. A young person who intentionally cultivates these skills through contemplative practices is likely to more easily focus on tasks and monitor ongoing distractions (whether it be their phone or an off-topic thought), reappraise their emotions about a friend, and dedicate full attention to a conversation.

Contemplative practices, if performed regularly, train the cognitive, emotional, imaginal and embodied dimensions of being human. For instance, attentional practices are understood to restructure cognitive processing in ways that significantly affect performance, which includes enhancing working memory, inhibitory control and executive functions (such as decision-making). Practices that emphasise the ability to monitor the contents of one’s awareness increase divergent thinking – a generative style of thought that lends itself to greater creativity and problem-solving. Embodied practices such as sustaining a certain physical posture, moving the body mindfully or attending to a sense perception can enhance motor awareness, kinaesthetic sense and tactile sensitivity.

The competencies acquired through contemplative practices can cultivate awe, flow and transcendence in individuals. These peak states are also associated with deft artistic and athletic acts, such as being ‘in the zone’. Indeed, the domains of contemplation, arts and sports can overlap in ways that highlight the benefits of contemplative practices: some artists practise meditation to allow the flourishing of spontaneity and creativity; some athletes, particularly those involved in precision sports, adapt contemplative training to reduce the overthinking that can impede their automatised executions in the field or on the court.

Humans have been using contemplative practices for a very long time. Among the earliest records from prehistoric painted caves – such as those in Lascaux in southwestern France, dating from 17,000 years ago – there is evidence that humans were reflecting on their environs, including animals, friends and foes, and the broader cosmos. Our current era, so infused with distraction, change and uncertainty, requires new ways of being in the world – a new know-how. In learning contemplative practices, we draw from the reservoirs of our human heritage to enhance our lives today.

Gaining fluency with the contemplative practices – like becoming an artist or athlete – requires not only time and attention, but social and institutional support. Where do we learn and refine the skills to be an artist or an athlete? We go to school. An intellectual education alone does not nourish the whole person. For that, schools additionally provide resources to train in creative and athletic skills – but very few other life skills, and fewer that promote flourishing and transcendence in the way contemplative practice can.

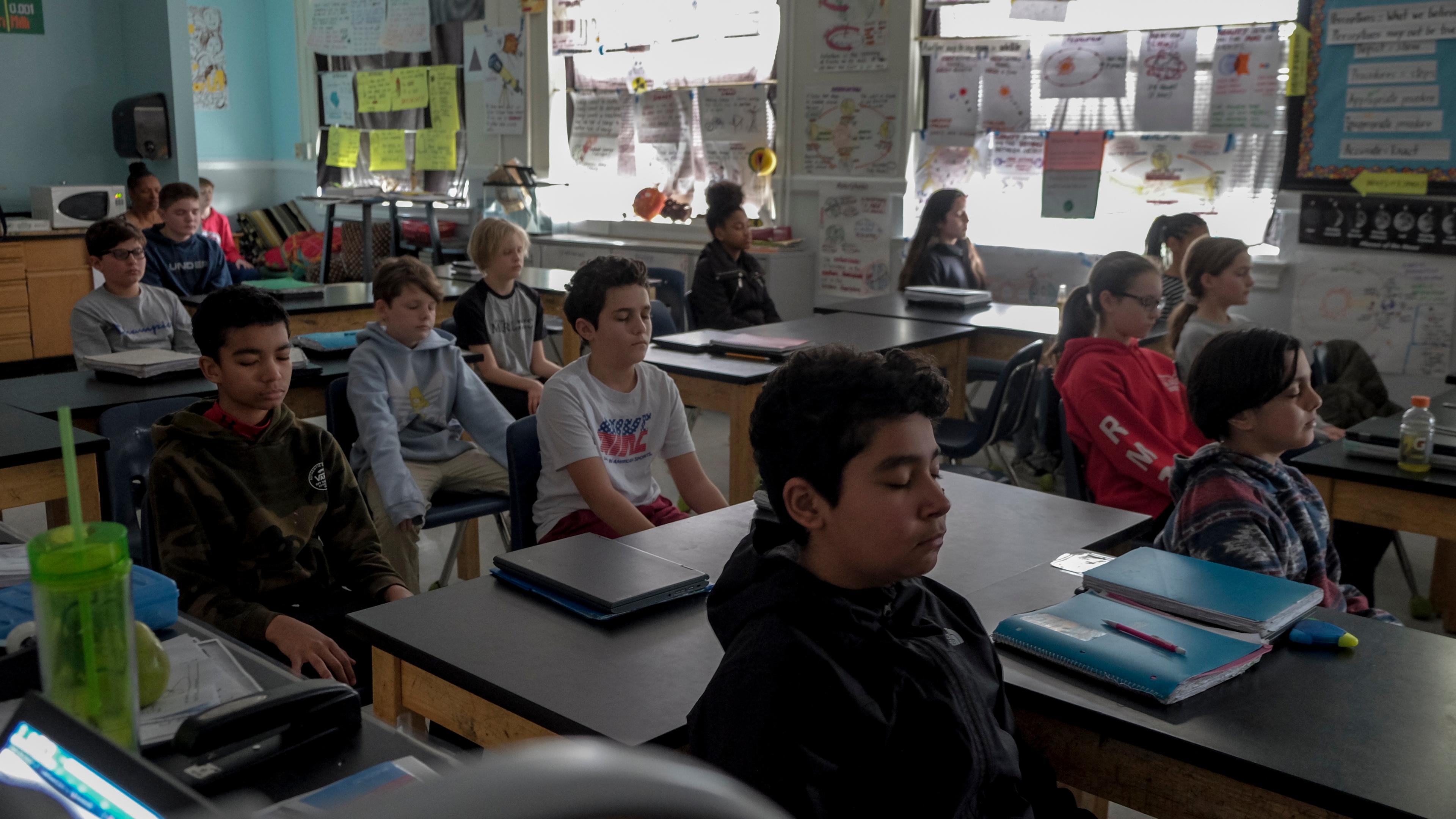

To support a culture of contemplation, educational institutions need to place a higher value on the inner life of young people. Schools could equip and empower students with contemplative toolkits – skill sets of multiple, complementary practices that can be learned through experiential training. To date, educators have predominantly approached this by introducing mindfulness and yoga into classrooms. This one-size-fits-all approach is riddled with cultural problems and too often overlooks individual differences and student needs. It’s important that the practices offered are intrinsically rewarding for young people – that they can observe tangible benefits in their lives, and don’t feel that such training is being foisted on them.

Aside from art or physical education classes, students don’t typically practise arts or sports in the classroom during regular school hours. Likewise, schools can offer specific times (after or before school) and places (studios, gyms, outdoor facilities) for teachers and coaches to personalise contemplative training. Schools, particularly higher education institutions, could offer contemplation as extracurricular programming, training young people in contemplative life skills and curating contemplative experiences by using mindsets and environments that induce awe, wonder and collective effervescence.

Given the current mental health and spiritual crises that young people face, it’s more important than ever for the adults who shape their education to decide whether we value the kinds of life-enhancing skills that are nurtured by contemplative practices. And if we do, we must invest in them – the way we do in other critical fields of learning and growth.

This Idea was made possible through the support of a grant to Aeon Media from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. Funders to Aeon Media are not involved in editorial decision-making.