Think back to the last television show or film you watched in which a character thoroughly captured your interest. Was that character a decent, average person, doing regular things all day? Probably not. That person who kept you watching might have been a noble hero. But it’s also likely that the character was, instead, a little devious. Or maybe more than a little. Often, the stories that people choose to engage with follow someone who is morally ambiguous or just plain bad. Some of our own favourite main characters, such as Don Draper of Mad Men, Marvel’s Loki or Arya Stark from Game of Thrones, are deeply flawed.

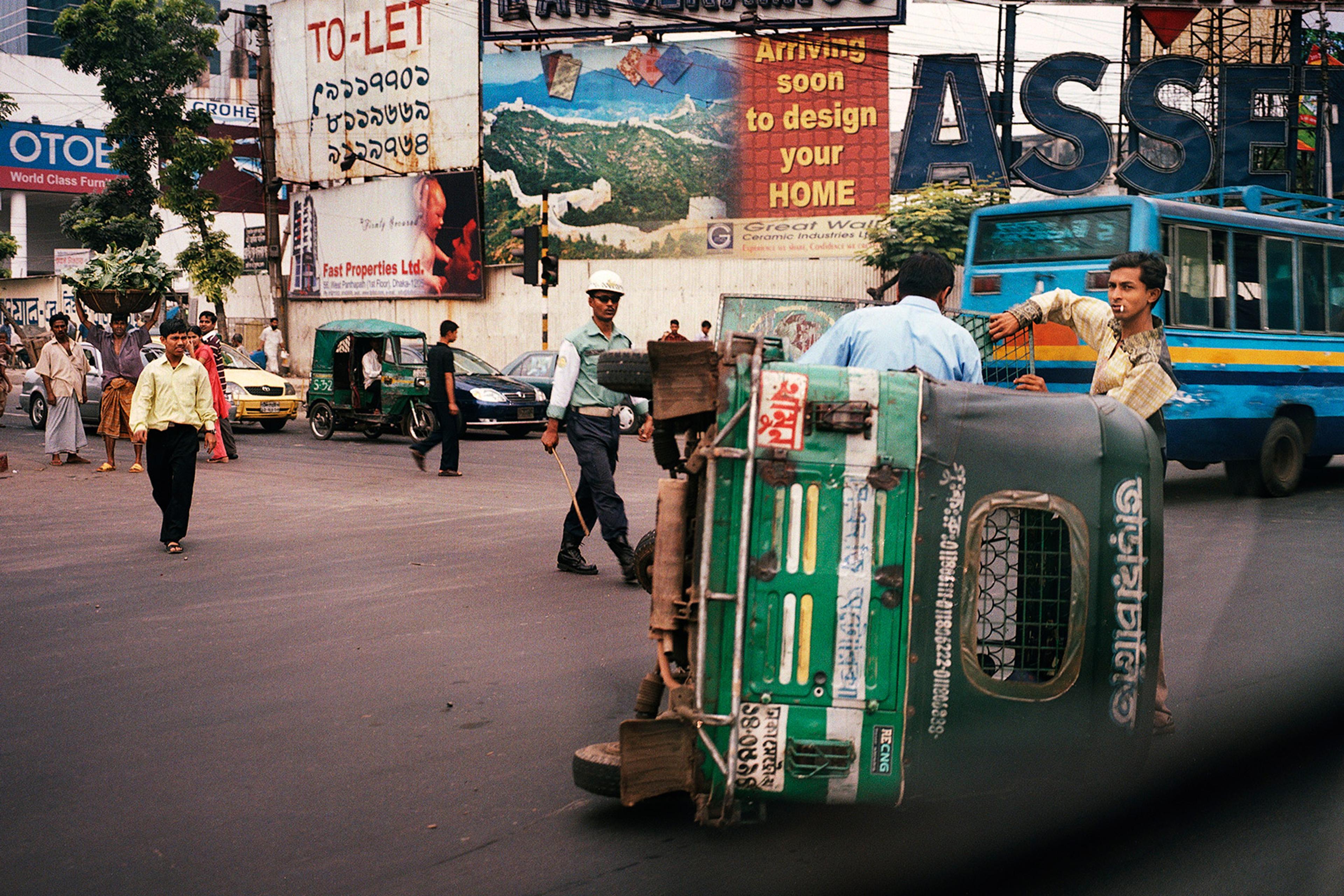

Audiences opt to spend many hours with characters like these. In recent research, we asked people about the main characters of the most-watched Netflix shows over a five-month period. Specifically, we asked them to rate how morally good or bad these characters were. We then examined how these judgments related to the total number of hours viewers spent watching the shows. We found that, on average, people spent more time watching shows with protagonists who were more immoral. Some of the most popular shows on Netflix during that timeframe included You (2018-), featuring a charismatic stalker and murderer, and Inventing Anna (2022), about the con artist Anna Sorokin (aka Anna Delvey). The correlation between time spent watching and the immorality of the characters held true even when accounting for factors such as show duration and genre, and despite our participants saying that the shows with more immoral protagonists were more effortful to watch.

Why do many of us seem to be more captivated by characters who do bad things than those who do good ones? The popularity of their stories suggests that these characters help meet some psychological demand in the millions of people who follow them on their journeys.

To start to explore this further, let’s consider two ways of watching a show about a killer. In one common scenario, you are rooting for the detective to catch and stop the criminal. In a film like David Fincher’s Se7en (1995), you follow the detective, who seeks to deliver justice and unravel the puzzle the killer has laid out. You are being asked to act as a third-party observer of the events that unfold and then to cast judgment on them. Another way to describe what you are often asked to do as a viewer is to practise your moral judgment: sharpening your sense of what is good and bad, and ultimately identifying with the good guy and condemning the bad guy. It’s relatively easy to see why people enjoy this kind of story.

A different way of watching the story of a killer is one where you are asked to identify with and relate to the killer. The show Dexter (2006-) is a good example. Dexter is immoral – he kills people! – but he’s also a family man and has a backstory that invites the audience to hope for his continued (murderous) success. He’s a classic antihero: he is someone who is bad but has redeeming qualities. In this case, Dexter adheres to a code that rationalises his murders – he kills only other killers (well, mostly). When watching Dexter, you are asked to spend a lot of time with him and feel along with him. In both Se7en and Dexter, the mind of the killer is intriguing, following an idiosyncratic set of rules; there is some puzzle to solve. Yet, in one, the killer is the protagonist, and viewers are invited to understand him and root for him.

Our research can help explain why people are so curious about protagonists like Dexter. We designed a task that showed study participants different sorts of individuals on a computer screen. In some cases, the person of interest was a fictional character, while in others, the person was depicted as a real-life individual whom the participants had not met. In both versions, the person varied in terms of how moral or immoral they were described as being.

We asked our participants to choose what to do next: learn more information about the person’s appearance, or learn more information about ‘the actions and experiences’ of that person. We found that study participants chose to learn about the actions and experiences of the immoral people – fictional or real – more than they did for morally good ones. This was true despite them reporting that doing so was effortful and more time-consuming than merely learning about someone’s physical appearance. Our research seems to suggest that people want to know why immoral people do what they do. They want to know what makes bad people bad.

Perhaps when we spend hours watching or reading about antiheroes, we are in search of this kind of information about the characters’ minds and motives. People are generally curious to understand the social world and the minds of others – which includes the bad things that people do to each other, and their reasons for doing them – and it may be that following around immoral protagonists helps audience members satisfy that basic desire. When we follow such characters, we are also getting to learn about extremes of social and moral life that we might not ever encounter personally.

The creators of fictional worlds – be it Dexter’s version of Miami or more fantastical settings like Asgard in the Marvel Universe – are engaging in a practice called worldbuilding. That is, they create a coherent fictional or fictionalised setting that situates characters in physical space and allows the audience to understand them psychologically. The audience gets to know their histories, personality, and the circumstances and struggles that shaped their beliefs and desires. For example, in the case of Dexter, viewers get access to his history of trauma, his own experiences with loss at the hands of a murderer, and a window into his conflicted feelings about his murderous desires. Worldbuilding allows us to make some sense of a wrongdoer’s behaviour in context.

In everyday life, people engage in their own kind of worldbuilding. You need to map the social and moral terrain in order to navigate it. Who is close to you? Who is powerful? Who is connected to whom? Just as geographic maps represent physical space, people also create internal representations of social space. Part of this social mapping, we propose, is representing what kinds of people and actions are possible and permissible. Engaging with fictional moral extremes can help a person chart this territory, filling in the map with rich details and many different kinds of people and relationships. Audiences may opt to engage with immoral characters for longer partly because, as research suggests, people’s understanding of individuals who are immoral (compared with morally good) is more precarious. And bad guys may offer especially rich information: bad things (people, actions, etc) often tend to be more varied than good things. There are relatively few ways to be good in the world, while there are many, many ways to be bad.

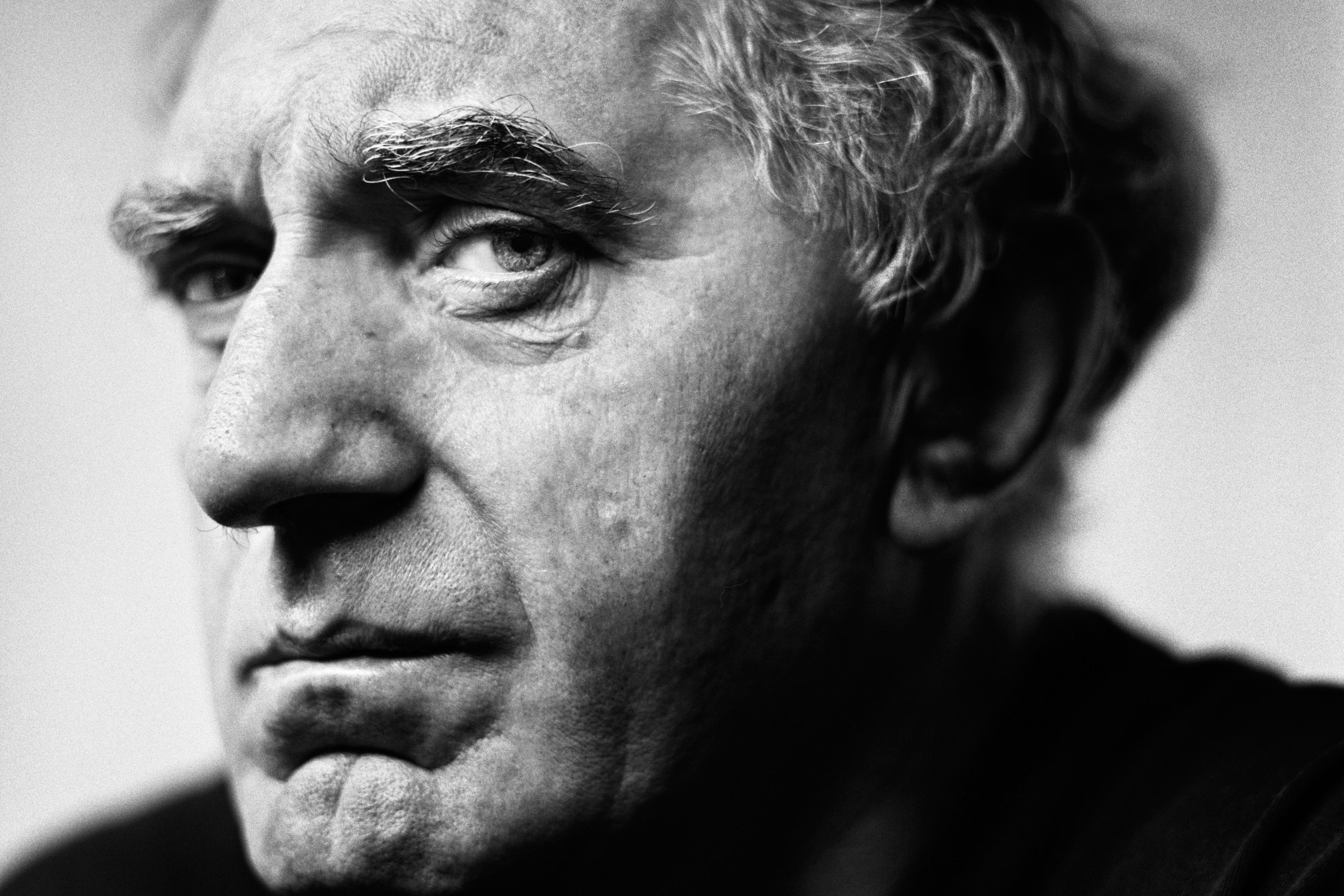

The allure of grasping why Dexter or Tony Soprano are the way they are draws us in

By gaining access to the motives and internal states of immoral individuals in books, TV shows, movies and more – information that is often not available through direct experience – audience members are able to make richer maps of the social world. Engaging with these fictional characters allows you to mentally travel to the far reaches of social acceptability, where there are charismatic adulterers and principled serial killers. You are exploring the outer spaces and possibilities of the map. We suggest that having a richer map of the social world, one that is partly informed by fictional immoral characters, likely helps people navigate the social world in real life. When someone engages with fictional characters in general, they are better able to understand why real people do the things they do, and may even become better at predicting what people will do next.

Indeed, people seem to have a sense that they have something to learn from morally ambiguous and immoral characters. Research outside of the moral domain suggests that one reason people are curious about explanations – curious for information about why – is that they think they will learn something valuable for the future. Learning seems to be part of what people want from immoral characters, too: participants in our studies chose to learn about the immoral people the most, and they also expected to learn most from the information about them.

Characters like Dexter or the mobster Tony Soprano capture viewers’ interest, then, because the allure of grasping why they are the way they are draws us in. As someone follows the in-depth narrative of a captivating antihero, the process of learning about their histories and circumstances brings with it the promise of understanding their motives and behaviours. And audiences learn about these characters’ minds with curiosity and sustained attention in a way that we seldom can with purely evil, unrelatable villains or even bad actors in our own lives – people with whom we might be unable or unwilling to follow along in the same way.

These narratives often ask the audience to set aside the typical role of judge and jury, and instead to join in – to feel alongside evildoers and criminals. Engaging with these characters is, ultimately, a social exercise; it shapes one’s understanding of moral boundaries in the real world, including what the boundaries are, how people navigate them, and why someone might cross them.