Thomas Carlyle in 1840 called the biblical book of Job, an ancient Hebrew work known more for its iconic subject than in its details, ‘one of the grandest things ever written with pen’, and he was right. The book is about a man named Job, who contends with his God as well as with his companions. Nevertheless, he is a paragon of virtue, whose commitments to truth and integrity override his piety, which makes his story relevant to any audience, regardless of religious, secular or even anti-religious orientation. The book draws on ancient legend, but it was composed around 400 BCE, when the Judean province of Yehud was governed by the Persian empire. The poet was probably writing for a small intellectual circle – his language is learned and dense. But in the version that has reached us are some additions interpolated by a reader or two who found the original version to be theologically offensive or even blasphemous.

For half a century, I have been studying, teaching and writing about Job. I devote my time and effort to this enterprise because I believe that this ancient poem with all its textual and linguistic challenges matters. In an era in which values and principles are continually assailed and eroded, the book of Job presents a profound brief for the virtues of values and principles.

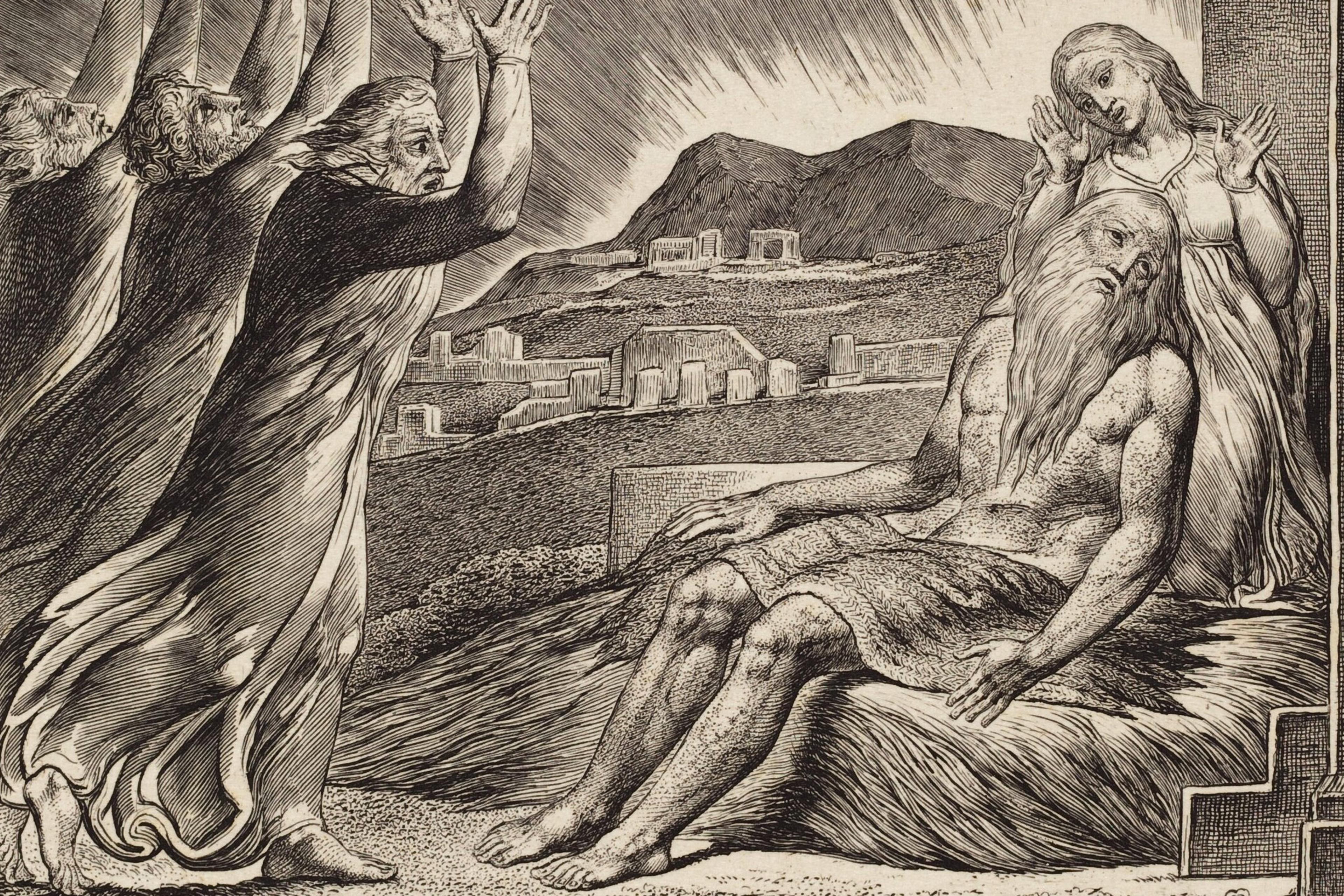

Before enumerating some of these, let me recap the drama. The deity wants to know how deeply devoted the righteous Job is. So he prompts the adversarial angel, the Satan, to divest Job of all his blessings – a wealthy estate, servants, children – in order to see if he would then curse God. When Job remains steadfast in his piety, the Satan is permitted to afflict Job’s person with a constantly irritating skin inflammation. Job refuses to abrogate his virtues. But then he is joined by three distant friends who console him on his losses but utter not a word about his skin – they are caught off-guard by the fact that such bad things could happen to so good a man. However, during seven days and nights of excruciating silence, Job has been re-thinking his outlook.

He curses – not the deity but his birth, his life:

Why couldn’t I be like a stillborn,

Just covered over (in the sand),

Like babies who never saw light?

– all translations from my book, Job: A New Translation (2019).

For Job, a life of suffering is a cruel imposition:

Why give life to one in travail?

Or life to those bitter of spirit?

Job’s friends are offended by this apparent critique of the Creator, and they engage him in a polemic over divine justice. At the same time, Job confronts the deity over the injustice he perceives, and these two interwoven arguments – Job vs his friends, Job vs God – develop throughout the book.

In the course of the dialogues, which comprise the large core of the composition, a number of antitheses stand out:

Debate rather than aggression. It should not need to be said, but in today’s climate of polarised discord, it might be healthy to recall that, although Job and his friends come to diametrically opposite conclusions, they resort to nothing more than rhetoric. Job begs the deity not to browbeat him into submission but, beyond the initial afflictions by which Job was put to the test, Job is done no further harm – and in the end is restored to his former position. Metaphors of assault abound, but the battle is joined in poetry, in words. Job anticipates that the deity may slay him for his protests, but he does not care:

I will take my flesh in my teeth,

And I will place my life-breath in my hand.

Though he slay me, I will no longer wait –

I will accuse him of his ways to his face!

When God answers Job, he berates him verbally – but he does him no physical violence.

Personal experience rather than tradition. In a time of alternative realities, it could be salutary to recall that, while Job’s companions warrant their claims with theory, with pithy platitudes that fly in the face of the situation at hand, Job justifies his contentions by appealing to the actual, to his personal experience. Thus, whereas Job’s friend Bildad reiterates the conventional wisdom of the book of Proverbs and declares:

The light of the wicked really does wane,

And the flame of his fire fails to glow;

The light goes dark in his habitation,

And his lamp goes out on him

– that is, the wicked, who in a just world ought to suffer, do in fact fail – Job counters:

(How often) does the lamp of the wicked wane?

And their ruin overcome them?

(How often) does he [the deity] dispense disaster in his anger?

Job harbours an expectation of justice from God – that the righteous will be rewarded, but also that the wicked will be punished. Job’s experience confounds his expectations. He feels personally abused and that, were he to challenge the deity, the latter would respond by incriminating him. He would, as Job puts it, take his ‘clean’, innocent person and cover him with filth, giving him the appearance of guilt.

Justice rather than power. Job has not read the book’s opening. He does not know that his suffering results not from divine punishment but from a test of his devotion. And so he believes that the deity is abusing him – accusing him falsely and afflicting him without justification. Job demands to see the charges against him:

How many are my crimes and my sins?

My transgression and my sin – tell me what they are!

But all along Job maintains that God is using his incomparable power to intimidate him and any potential arbiter:

If it’s a matter of strength, then he is the strong;

And if a legal proceeding, who can convene us?

Even if I were in the right his mouth would condemn me,

(Even) were I innocent, he would wrong me.

When the deity finally appears to Job from the windstorm, he demonstrates his awesome power as the creator and controller of nature and especially of the terrifying creatures within it; but he barely refers to justice and minimises his concern for people. That is why Job in the end expresses his utter dismay and, in my translation, laments:

That is why I am fed up!

I take pity on ‘dust and ashes’ [a biblical figure for abject humanity] …

Job sought justice, but God showed him only power.

Truth rather than pretence. Truth might be relative, dependent on certain premises and construal of the facts. But there is a difference between the truth that you believe because it accords with what you know and the pretence of truth, which is no more than a projection of what you would have people believe. Job would not compromise his truth, because he could not, for the life of him, find serious fault in his conduct. And both the narrator and the deity had told us at the start: Job is ‘whole (in heart) and straight (of path), and fearing of Elohim [ie, moral] and turning from evil’. Job’s truth is the truth that is stipulated in the book. It is therefore pernicious that, by presuming Job’s suffering is some sort of divine affliction, Job’s companions deny his truth and promote their own – without having any evidence to support it other than the fact that Job seems at odds with God. For me, the climax of the book comes toward the end, when the deity, in a stunning turn of events, reproaches Job’s friends and praises his ‘servant Job’, because he spoke about God, not in conformity with convention, but ‘in honesty’. The companions, and perhaps the reader, had expected that the deity would appreciate any and all defences of his honour. But the poet, in what I would not hesitate to call a subversive move, stands opposed to the pieties of Job’s companions, which ignore reality, and squarely behind Job’s truth – not necessarily ‘The Truth’ but the truth that Job believes. The deity astonishingly salutes Job when he speaks his truth to the deity’s power.

Integrity rather than corruption. The God who flexes his muscles before Job, and who refuses to reveal the backstory to his suffering, continues to admire Job for his absolute integrity. Job is honest to a fault:

So long as there is life-breath within me,

And in my nostrils Eloah’s spirit,

I swear that my lips will speak nothing corrupt,

And my tongue will utter no deceit.

He refuses to bow to the peer pressure of his friends and admit to some wrongdoing, when he can find none:

God forbid I declare you in the right –

Not till I expire!

I will not set aside my integrity.

I hold fast to my righteousness;

I will not let it go.

Job’s interest is not in self-preservation but in self-vindication. He had enjoyed the status of local magistrate in his town. Insolent youths would hush themselves in his presence; the elderly would rise for him. He took great pride in providing justice for others, but the stigma of his afflictions led his compatriots to withdraw from him. Job is therefore doubly wronged: he is the object of injustice, and he is prevented from doing justice for others.

Interpreters of Job throughout the ages have seen Job as an everyman. But clearly he is not. Thankfully, few suffer as much as Job. And few so bravely stand for their truth.