In 1723, Jean Pillot and Marguerite Perricaud began to see each other often. They both worked in textile production in Lyon, France’s second city. They went out for a year and he promised marriage. She told him he had to ask her father. They took long walks together after work and on Sundays, during which they developed a physical and emotional intimacy that paved the way for marriage. Marguerite told a co-worker that they loved each other. Young couples’ talks about sex were tightly woven into discussions about matrimony. Neighbours often saw them together. Their relationship developed as a public matter in view of the community.

One evening, Jean came into Marguerite’s room with a lit candle and locked the door with a key. As she recalled later, he insisted that he loved her, and promised that he would never have another woman. Then he seized her by the arms, threw her on the bed and, despite all her resistance, had sex with her twice, all while continuing to promise that he wouldn’t be with other women and she didn’t need to be afraid. They continued to see each other and to have sex because, as she explained later, she still expected to get married.

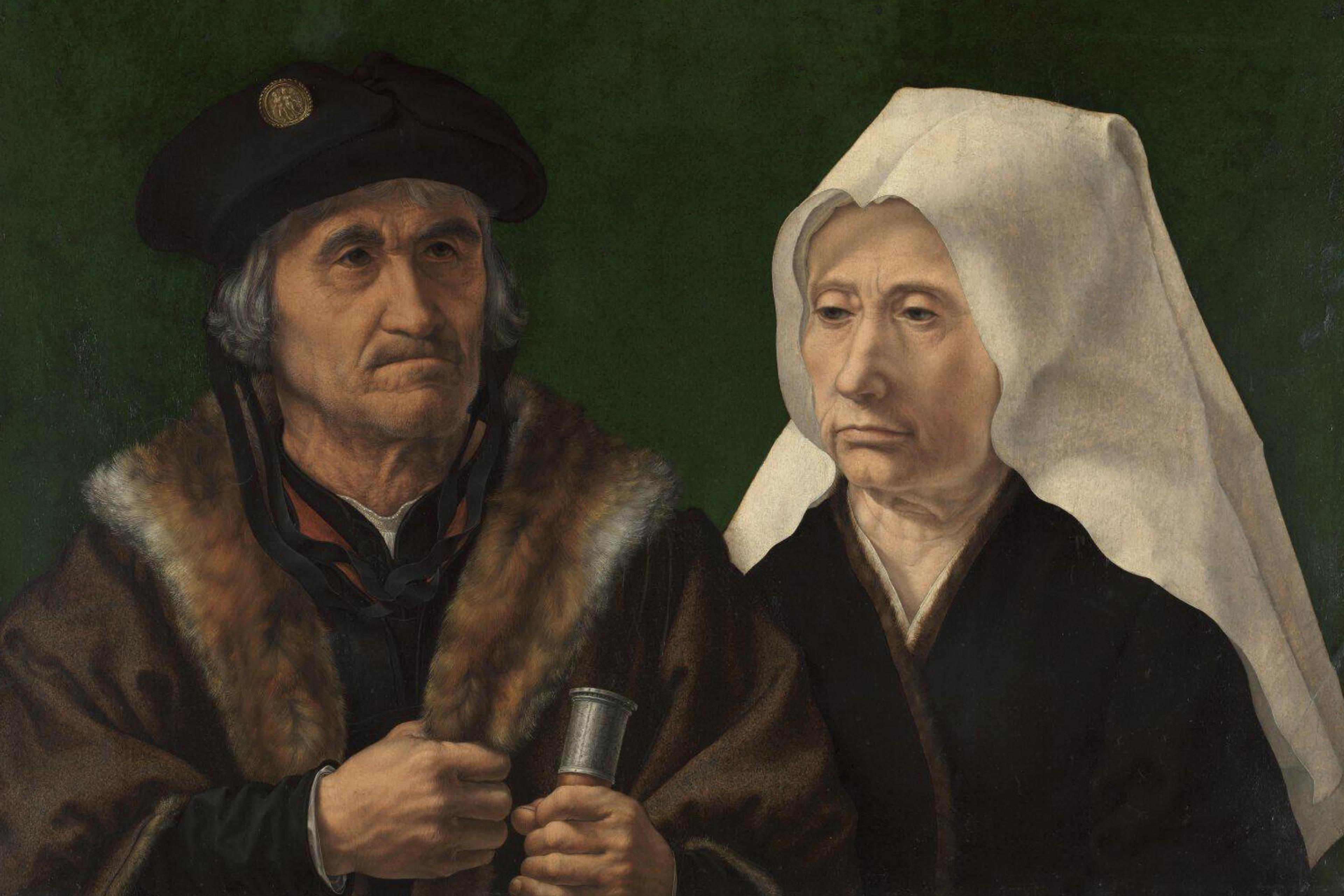

The social life of single people in 18th-century France and in other parts of northwestern Europe lasted about a decade. It started when they began to work in their mid-teens and continued to their mid- to late-20s, when they married. Much of Lyon’s old city in which young people lived, worked, loved and sometimes fought still survives today, with its multistorey tenements, courtyards and narrow cobbled streets. Luxury silk production dominated the economy of 18th-century Lyon, and it employed thousands of young men and women in skilled jobs. The trade in allied goods such as gold or silver thread and decorative trims also employed many thousands of young people. Some single women worked as servants because every household at the time, no matter what rank, had at least one female servant, although fewer than elsewhere because many young women preferred the textile jobs that were available in Lyon.

The 18th-century world of young people’s intimacy is recorded in the city’s archives in a long run of paternity suits that pregnant young women sometimes filed when their boyfriends failed to marry them. The women told their side of the story and witnesses – neighbours, co-workers, employers, friends – gave their accounts of the relationships. Sometimes, personal items that young women deposited as evidence, such as promises to marry or letters, also survive.

Nothing was unusual about Marguerite and Jean dating, and having sex, in 18th-century France. Young people often dated co-workers. Workplaces could be opportunities for flirting and sometimes more after couples committed to marriage. Anne Rubard and Jean Claude Fiancon, for example, worked as partners on the same loom. Their employers watched their relationship develop as they took walks, went to Sunday mass together, and sometimes worked very late, long after others went to bed. They talked about getting married and he wrote her an effusive promise to marry. As Anne recalled later, with the decision to marry seeming firm, they started to have sex. On occasion, they took the opportunity of late-night work shifts to have breaks for sex.

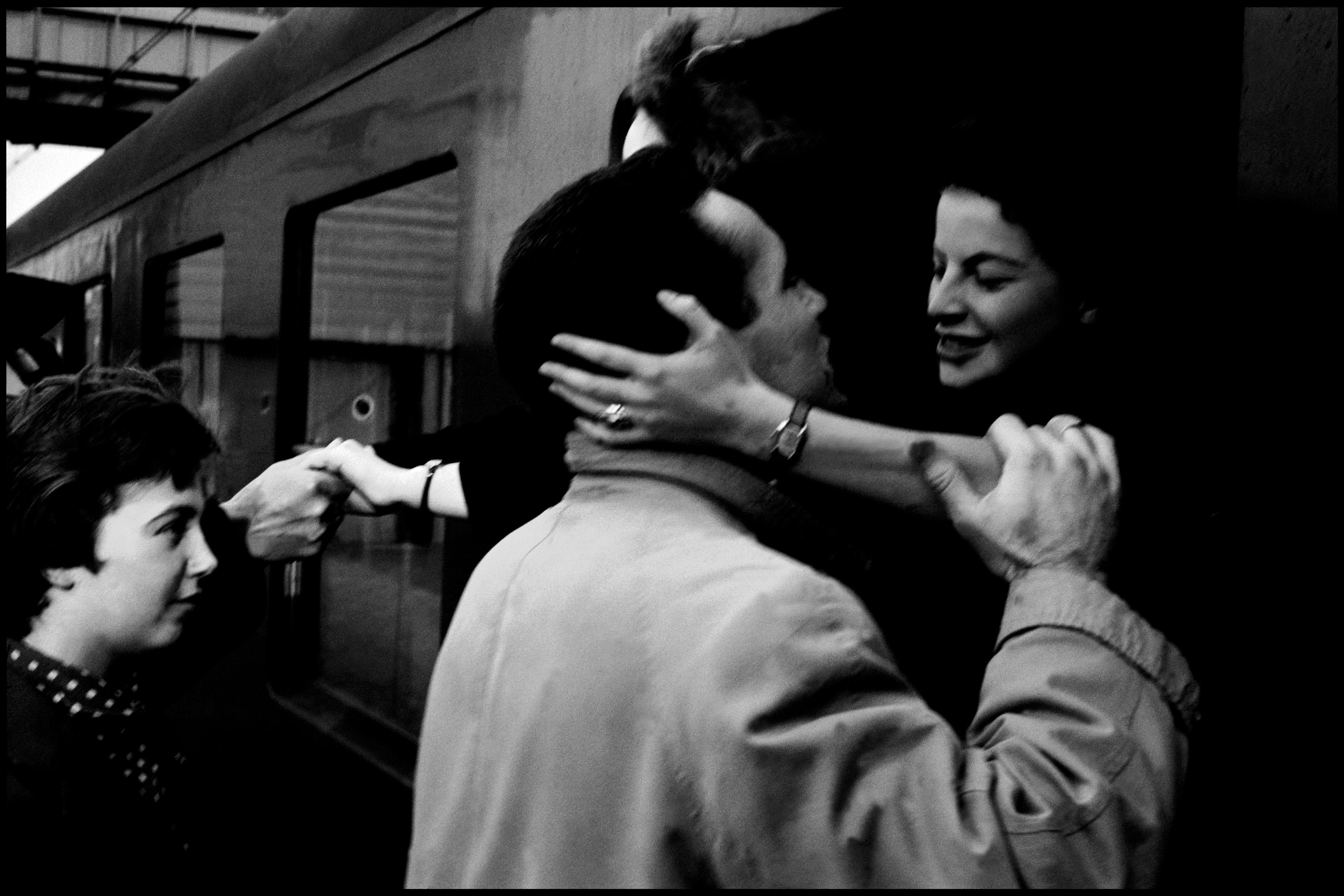

Young women as well as men often seem to have enjoyed physical intimacy. Neighbours and friends remembered how they saw young couples making out: young couples kissed on the mouth, young men touched their partners’ breasts, or put their hands up skirts. Communities saw a wide range of intimacy short of intercourse as normal. As one neighbour said, after remembering that he’d often seen a young couple make out, ‘so I didn’t see anything inappropriate’.

‘Marriage’ involved a multiple-step process rather than a ‘wedding day’ that marked a sharp break between single and married status. The frequent walks were social displays of coupledom that also kept their activities in public view. Promises of marriage usually led to intercourse, and young women often recalled the use of force as integral to that shift. Couples made marriage contracts that specified dowries and affirmed parental permission. Their parish churches read out banns that publicly announced the couple’s intention to marry and invited anyone to speak out who knew why they should not. The religious ceremony was brief, held at the door of the church with just a couple of witnesses. Sometimes a celebratory dinner and drink with friends followed. Pre-marital conception was common and regarded as routine and predictable in such a multi-stepped transition. It became a problem only if the parents failed to marry before, or not long after, their baby was born.

Couples had explicit talks about sex and about efforts to interrupt reproduction. Young women knew that they should be careful about intercourse because they were likely to get pregnant quickly, and sleeping around damaged their reputations. They tried to be sure that their partners were serious about marriage, sometimes – like Anne Rubard – getting written promises to marry that they could show their friends and neighbours in a kind of forerunner of showing off engagement rings. When they got pregnant, they sometimes took that as a sign to move forward with the other steps to marriage, and young men might say something like: ‘Don’t worry, we’ll get married.’

On other occasions, if one or both of them were not in fact ready to marry, couples often collaborated, negotiated or argued about efforts to interrupt reproduction. Young men could buy ‘remedies’ designed to ‘restore’ their partners’ menstrual cycles, de facto purgings that caused young women to be so ill that they spontaneously miscarried. They often tried having surgeons bleed women, a medical intervention thought to cure many ills, and sometimes they argued about what to do. When Anne Julliard became pregnant for a second time, she refused her boyfriend’s suggestion to take a remedy again because it had made her so ill. He offered another solution: if she delivered the baby and hid it under the blanket, he would come to take it away. What he would do with said baby to solve the problem remained unspoken, at least in the surviving record.

When young men told their girlfriends not to be afraid, whether about first intercourse or a pregnancy, young women pointed to the risks of sex. The guy might not marry them when they became pregnant, leaving them to face a hard path as a single mother. Pregnancy, interrupting pregnancy or delivery might threaten their lives or health. Risks for men were not negligible. Friends, families and employers expected young men to take responsibility for the reproductive consequences of their sexual activity, if not by marriage, then by taking custody of the baby and paying their partner’s costs. Young men who refused could find themselves in prison if their partners filed paternity suits with local courts.

For us today, the use of force in first intercourse in ongoing relationships headed towards marriage is jarring. In our age of #MeToo, physically coerced sex is a newly visible stigma. But 300 years ago, the fear and pain for women whose intimate partners locked them in and held them down to have sex was a routine part of their relationships. Ordinary violence was a mundane part of daily life. Husbands and employers were allowed to beat their wives, workers and children under the guise of discipline. Rape was almost never prosecuted. Prevailing family law (coverture, which subsumed a woman’s legal person under her husband’s) gave men the right to discipline their household members and manage their property, and also served culturally to entitle men to access to the bodies of their soon-to-be wives. Perhaps young men expected first intercourse would go like that, and young women knew that it likely would too. When young men locked the doors, they kept out neighbours, roommates or co-workers to secure some privacy in a world where working people always shared rooms. Indeed, sex in a bed was often euphemised as ‘what husband and wife do’.

What do these 300-year-old experiences of heterosexual sex in stable, affectionate, consensual relationships tell us about our own times? Some differences are clear. We sentimentalise marriage as part of romantic love, and are surrounded by media messaging that we should be great at sex and that great sex is essential to our relationships. However, 300 years ago, despite plenty of bawdy songs and the emergence of pornography in cheap print, young people didn’t have such high expectations. Today, we have reliable contraception and (in some places) legal abortion to control reproduction. We eschew violence as a part of healthy sexual intimacy. Marital rape is now a crime in Western countries.

Yet, young couples often live together before marriage and premarital sex is a widely observed norm, albeit rarely linked to matrimonial prospects. More babies are born out of wedlock than ever before. Even ‘bridezilla’ weddings, sometimes after parenthood, are only one step in a gradual transition. The strictly monitored courtships and no sex (or no knowledge even of sex) before marriage that my grandmother told me about are largely things of the past, as is, on the whole, the stigma of an out-of-wedlock pregnancy. Young couples or young women still find themselves facing hard decisions about interrupting reproduction when faced with untimely pregnancies, infanticide still occurs, and intimate partner violence is still all too common.

Perhaps nowhere more than in terms of (hetero)sexuality does history depart from the Whiggish tale of ever-increasing freedom, and the long history of sex is full of lusts satisfied and norms of robust sexual expression and happiness in many historically specific iterations. And seemingly inevitably, conflict and disappointment have long been frequent elements of intimacy too.