Many situations in life that are supposed to be fun also involve a high degree of uncertainty: dates with strangers, rollercoasters with unpredictable twists and turns, unrehearsed karaoke. For those of us who like to be able to see what’s coming, many of these potentially enjoyable opportunities may as well have warning signs hanging over them. Sometimes it’s tempting not to take the risk. But I recently came across a study that made me wonder if I should challenge myself more often.

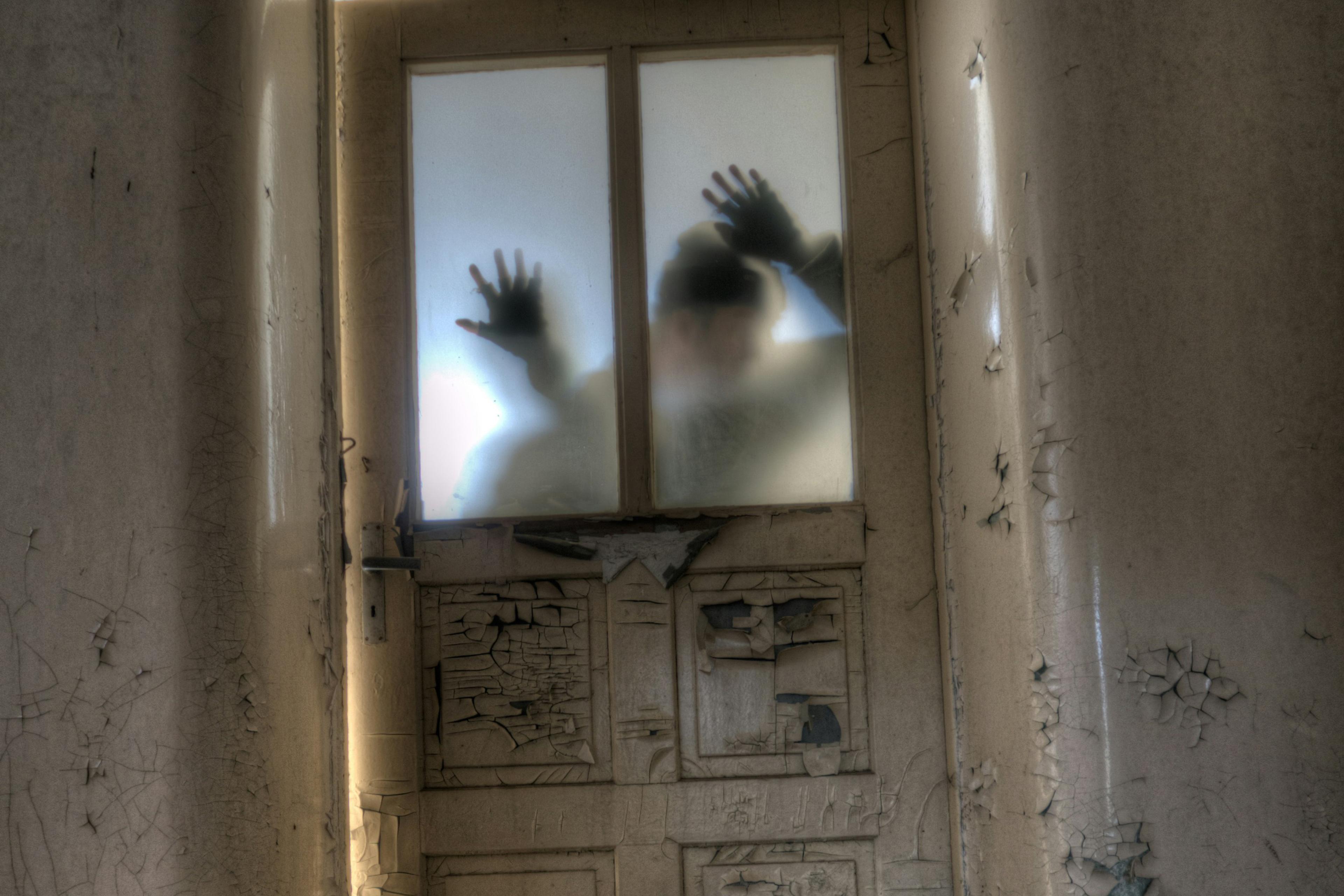

The researchers, including members of the Recreational Fear Lab at the University of Aarhus in Denmark, surveyed visitors to Dystopia Haunted House – one of those immersive attractions where you wander past menacing costumed actors, not knowing what will pop out next. Before they went in, the participants completed some questionnaires, including one tapping their intolerance of uncertainty. (They rated how much they agreed with statements like ‘I can’t stand being taken by surprise’ and ‘Uncertainty keeps me from living a full life’.) As you might expect, visitors who were less tolerant of uncertainty had dimmer expectations about how the haunted house would hit them. They anticipated less positive emotion and more anxious and generally negative emotions than the uncertainty-tolerant did. And yet, afterwards, visitors across the board (including the uncertainty-averse ones) reported feeling more positive emotions and less unpleasant emotions in the haunted house than they predicted they would.

In other words: despite the frightening surprises they’d encountered, it wasn’t so bad after all. It seems that for me and other certainty-craving people, the real problem might not be the ghoul hiding around the corner or the possibility of singing off-key at the karaoke bar, but our pessimism about how it’ll make us feel.