When you’ve had a bad day, or even a bad year, have you ever reached out to your friends or family, only to be met with a sea of saccharine assurances such as ‘chin up’ or ‘everything happens for a reason’? Perhaps you’ve approached your boss with a burning gripe to get off your chest, only to be confronted by a new sign on the door saying ‘Positive vibes only!’ Or you might have seen the endless self-help books, courses and TikTok gurus promising that a life of happiness is only a positive affirmation away.

It’s easy to see the appeal of the idea that you can make yourself happy and successful purely with the right mindset and attitude. Even if the types of claims made by self-help gurus strike you as ridiculous and over the top, you might think ‘What’s the harm?’ But the pressure to be unwaveringly optimistic in the face of all obstacles poses a threat to our personal and collective wellbeing. That’s why some experts have started referring to the modern cultural insistence on cheery conformity across all situations as toxic positivity.

I experienced a stark example of toxic positivity when I was a trainee counsellor. I had a supervisor who believed that negative thinking ‘manifests’ illness. She insisted that people must ‘clear’ themselves of negative beliefs and memories, and maintain a positive outlook in order to stay healthy. In a group mentoring session, when another trainee shared the sad news of her cancer relapse, our supervisor bellowed dismissively: ‘Oh, you just keep popping those things out, don’t you!’ The trainee left, deeply hurt, never to return.

Toxic positivity hasn’t arisen out of nowhere. There is more than a kernel of truth to the idea that a positive mental attitude can be beneficial. In fact, there’s a field dedicated to studying these benefits – ‘positive psychology’. Research in this area has shown that people who take a more positive and optimistic attitude to life often end up less stressed, less depressed, and generally have better health and wellbeing outcomes. Plus, being a positive person is attractive to others, and the social benefits that come from this are also key to wellbeing.

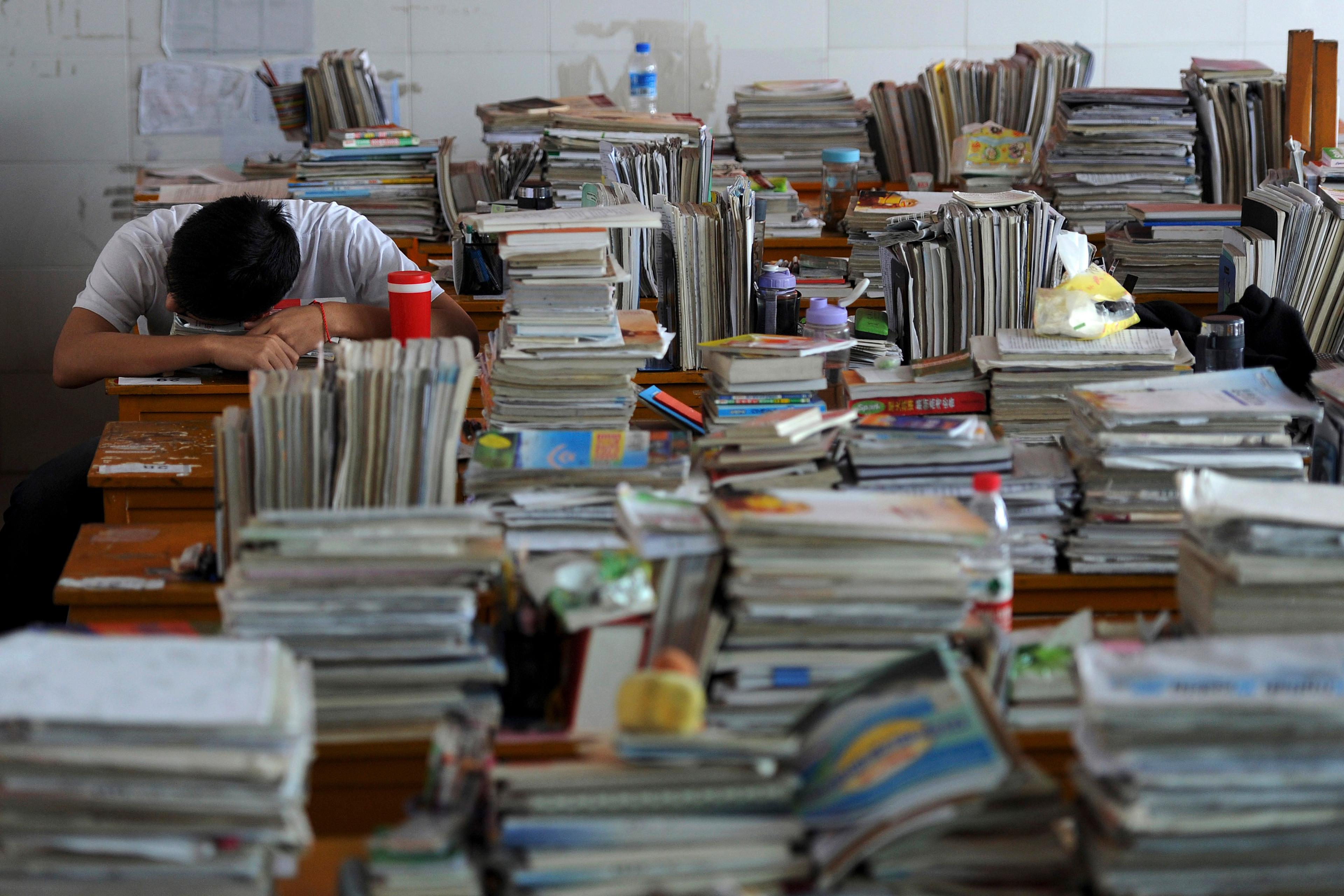

However, scholars have criticised the findings from positive psychology for being overblown or too simplistic. It’s important to understand that positive psychology interventions tend to most benefit those who are generally psychologically healthy already. In other words, people struggling with intense psychological problems or life circumstances probably won’t get the same benefits from positive psychology, compared with pursuing more established treatments such as cognitive behavioural therapy. What is especially unhelpful or even harmful is when people take positive thinking to an extreme and believe it is the answer to any problem. Unfortunately, this is the overly simplistic positivity message that’s being broadcast to millions.

With their latest hacks, ‘lucky girl’ attitudes to life and hero narratives of overcoming any adversity through unwavering determination, online influencers often promote this shallow version of positive psychology. To their many followers, such portrayals become the benchmark for what we should all aim for in life.

Having absorbed these idealised norms of positivity, people might come to believe their natural reactions to inevitable difficult experiences in life (be it bereavement, job loss, pandemics or relationship failures) are somehow wrong. They risk developing habits of experiential avoidance: the consistent denial, suppression or avoidance of difficult thoughts and emotions. Of course, it’s fine to put on a happy face to get through a rough meeting, or positively reinterpret a situation to cope with momentary hassles but, at some point, we all need to stop and address our ongoing unresolved problems and issues.

Avoidance can reinforce the idea that there are ‘bad’ inner experiences that need to be avoided. But it’s not so easy to avoid our inner experiences. Have you ever tried not to think of a purple elephant? Experiments have found that when people try to do this, they end up thinking about them more, not less. This lends weight to the old adage from the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung that ‘what you resist…persists’.

The extra effort and energy expended on avoiding things through thinking positively can cause stress

Labelling certain thoughts or emotions as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ can also create a needless cycle of self-judgment and atonement for nonexistent sins. Let’s say you come to believe that a thought you have about someone is ‘bad’. This may cause you to feel guilty that your behaviour doesn’t match your stringent moral rules. Following the positivity gurus, to escape this cognitive dissonance, you might paint over this thought with positive affirmations, trying to reduce the discomfort and convince yourself you’re actually a ‘good’ person. Yet all of this rigmarole actually gives the ‘bad’ thoughts more power than they need to have.

Ultimately, the extra effort and energy expended on avoiding things through thinking positively is likely to cause stress. Paradoxically, this stress then puts you in the firing line for the very same mental and physical health issues you were trying to avoid through positive thinking! A longitudinal study found that people whose coping style involved avoiding problems reported more stressful life situations four years later and more symptoms of depression 10 years later. Trying to suppress negative emotions has also been linked to physical health issues and potentially even earlier death.

Not all situations in life require a positive slant. There are times when sober, uncomfortable reality is useful. For instance, negative feelings or experiences might motivate someone to seek out a diagnosis and treatment for illness, address their mounting debt, or leave a bad relationship. Sometimes we need to address the uncomfortable aspects of ourselves. Jung suggested that striving for moral perfectionism denies the more complex, less socially acceptable parts of our personality; that it can hinder true self-acceptance and growth.

Similar problems arise when we place rigid standards of positivity on others. The ‘positive vibes only’ mentality can hinder open and empathetic communication in social and professional settings. For example, insisting on positive vibes at work may discourage colleagues from voicing concerns, and leave genuine issues unaddressed. The same in our close relationships. My own experience with my supervisor taught me to reconsider whether well-meaning and seemingly banal reappraisals of others’ situations such as ‘look on the bright side’ are beneficial. Sometimes people just need a good listening to. Embracing the full spectrum of human emotions, including those that are uncomfortable or painful, is vital for genuine connection and understanding.

So how do we navigate the fine line between effective positivity and excessive or toxic positivity? Unlike the TikTok soundbites, the answer is nuanced. Take the positive affirmations and visualisation techniques that are so wildly popular among social media influencers and gurus. Research suggests that positive affirmations (such as repeatedly reminding yourself of what you’re good at or what you like about yourself) can indeed help people feel better about themselves, but the benefits are mainly seen in those who already have a more positive self-image. For those grappling with very low self-esteem, affirmations can backfire, making the person feel worse. This adverse effect may stem from the cognitive dissonance that occurs when these positive statements clash with someone’s self-image. If an affirmation such as ‘I love everything about myself’ is so obviously a lie, it not only makes you remember all the things you don’t like about yourself, but also makes you feel like a liar too.

Similarly, the value of positive visualisation is also nuanced. Research by the German psychologist Gabriele Oettingen has shown that merely having an inspiring vision of the future isn’t sufficient to better motivate us towards our goals. We need a balance between indulging in inspiring positive fantasies and confronting the realities of our circumstances, meeting ourselves where we are.

Rather than aiming for constant positivity, the lesson taught by many modern psychological approaches – such as acceptance and commitment therapy and dialectical behaviour therapy – is the importance of accepting and understanding how things are. They focus on helping build a more compassionate and accepting relationship with our inner experiences. This may work because, when we lessen the negative judgment, the ‘bad’ thoughts and feelings end up, paradoxically, having less power over us, allowing us to unhook from these inner experiences more quickly, without having to expend energy trying to get rid of them altogether.

Excessive positivity, while well intentioned, can silence the genuine struggles all of us face

So, the key to wellbeing might be the ability to balance a positive outlook with accepting and engaging with how things actually are. This reminds me that the Alcoholics Anonymous serenity prayer is as pertinent today as it was in the first half of the last century: ‘God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.’ How can you find the wisdom to know the difference? I think everyone has their own path, and it’s always a work in progress, however, here are some suggestions based on my research and experiences in the self-help space:

- It’s helpful to notice when you feel pressure from others to be positive, be it your friends, family, colleagues or social media celebs. You might notice it when you’re scrolling through your feeds, comparing yourself with others, for example. In these situations, it’s important to remember that what you’re seeing is a curated and cherrypicked version of how people live their life. It’s not the whole story.

- When people or groups valorise positivity and demonise expression of ‘negative’ thoughts or emotions, this is a red flag. Sometimes these strict moral rules are used to shut down dissent and critiques. This is not very healthy long term, as it stifles genuine expression and hinders change. It’s good to remember that there are times and places where negative thoughts and experiences can actually be helpful.

- Positivity can spontaneously arise in different ways for each of us. It could be when you’re volunteering, playing music, walking the dog, taking an improv class, talking with a friend or cuddling your child. Find what makes you feel good, and give yourself permission to do this more often. For many people, this softer approach to being happier each day is more effective than having to adopt a specific mindset or to think the ‘correct’ thoughts in order to be happy.

In the face of a cultural insistence on positivity, we need to remember that life’s not just about the social media highlight reels. It’s about the whole movie and even the pieces we leave on the cutting room floor. Excessive positivity, while well intentioned, can silence the genuine struggles all of us face and can create an environment where only certain sides of ourselves are valued, forcing us to wear masks that don’t always fit. To improve our individual and collective wellbeing, let’s embrace the full spectrum of our humanness and foster spaces within us and around us where it’s OK to be OK, and also OK not to be OK.