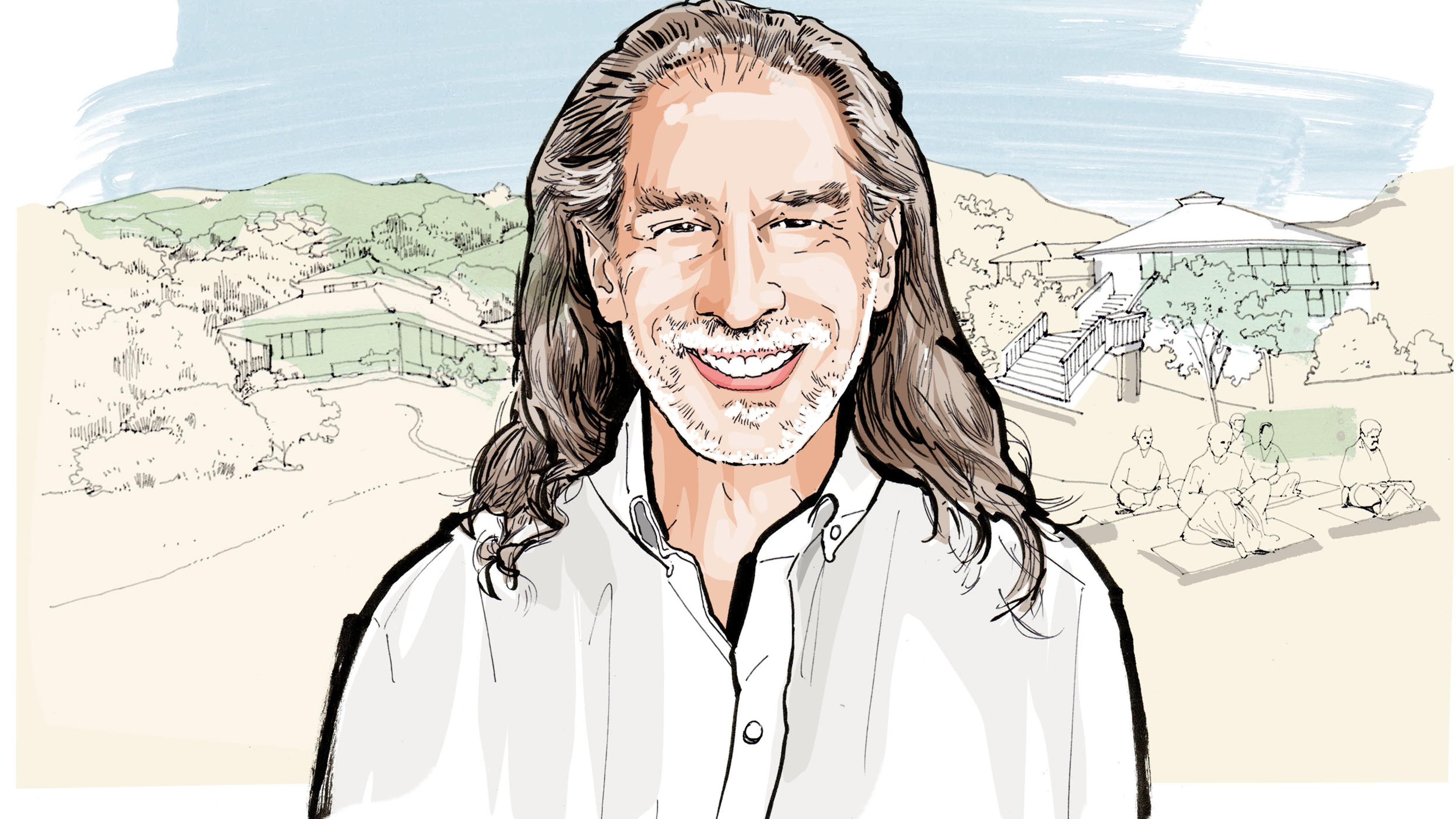

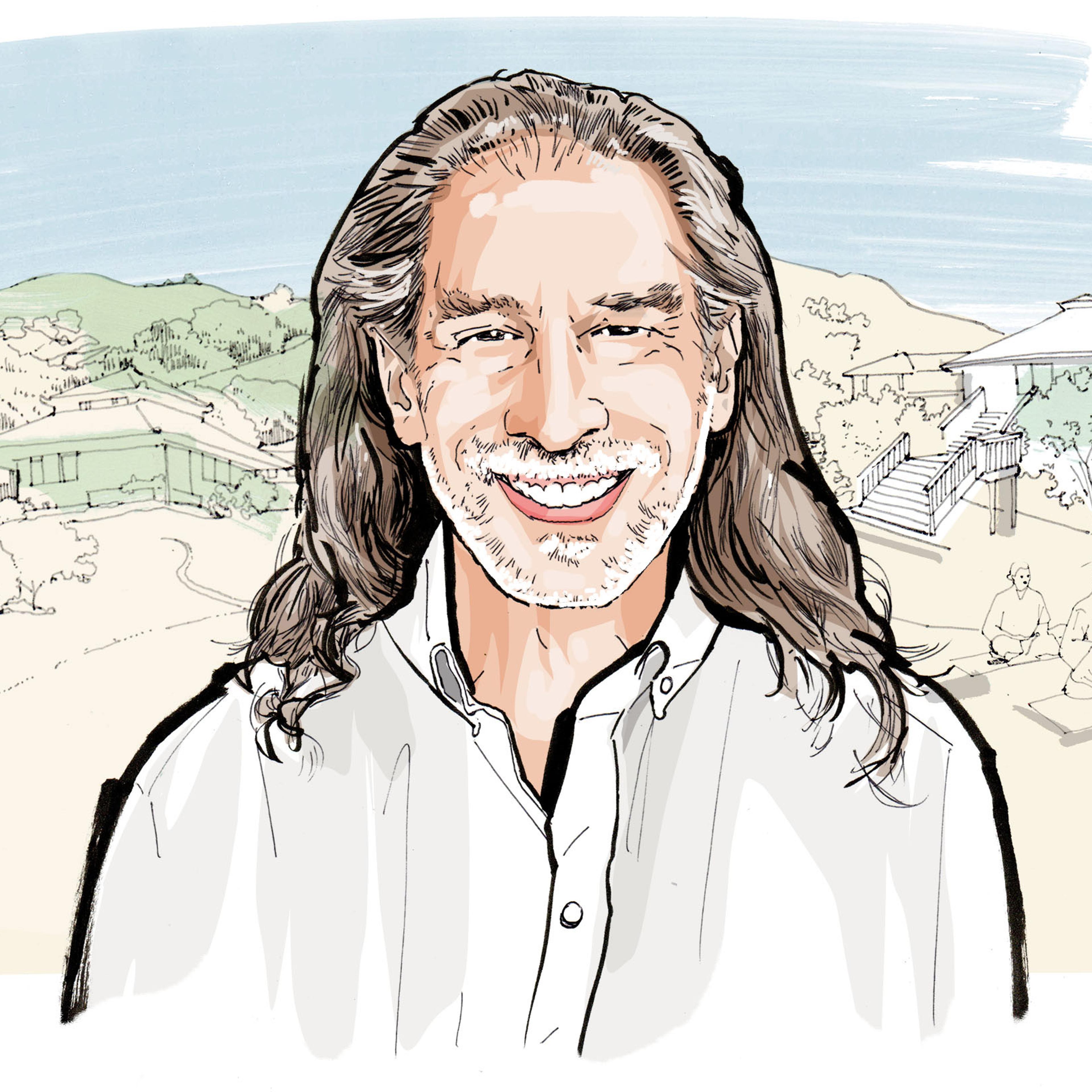

Editor’s note: in the final months of his life, Steve Schwartzberg welcomed the writer Andrew Lawler into a series of intimate conversations that helped him shape this portrait. Known for workshops that fearlessly explored the erotic, meditation, and the dying process, Schwartzberg set aside many recent afternoon hours to reflect on his path, his teachings, and his conscious embrace of what he called ‘the transition’ – culminating in his death on 10 December 2025.

Summer was waning and the sand was cool as Steve Schwartzberg sat alone on the beach beside Captain Jack’s Wharf in Provincetown, Massachusetts. A Monday morning stillness had replaced the weekend bustle of shirtless men and drag queens sauntering down nearby Commercial Street, where dour Puritans had first stepped ashore four centuries before. Now it was the bright pink heart of New England’s gay mecca.

As he looked over the bay, the slim, youthful, dark-haired man dropped into a mental reverie. ‘I was just a horny 40-something gay man having fun in Ptown,’ he recalled. Then, as he basked in the rising sun, a voice like ‘an inner megaphone’ interrupted the reverie.

The message was as clear as the calm September morning in 2002: ‘Open your life.’

Schwartzberg was outwardly successful, with numerous friends, and unencumbered by debt, a partner or children. A clinical psychologist on the faculty of a mental hospital affiliated with Harvard, he had a private practice in Cambridge, MA and could afford to rent a pricey apartment on summer weekends. Yet he harboured a vague but persistent anxiousness.

As he pondered the stark message, his accomplishments seemed anything but meaningful. ‘People lead all kinds of lives and then they die,’ he thought. ‘There are no rules, only suggestions.’

Schwartzberg wasn’t sure how he would do it, but at that moment he decided to step off his conventional path and take a brief sabbatical. ‘I had zero idea that I was taking the next 18 years off,’ he told me. That journey would turn him into a globe-roving sexual healer and spiritual guide.

He could not have chosen a more fitting site to begin his unusual quest. Captain Jack’s Wharf had been known in the 1930s as ‘whoopie wharf’ for the sexual shenanigans within the ramshackle cottages perched on the pier. ‘The whole lunatic fringe of Manhattan is here,’ Tennessee Williams told a friend in 1944.

This was a place where the power of erotic performance and introspection had long come together above the rise and fall of Cape Cod Bay. Captain Jack’s Wharf, he said recently with a laugh, was ‘also where Steve Schwartzberg discovered God.’

Most of us daydream about a free-spirited life, unmoored from traditional notions of success and respectability. Steve Schwartzberg is that exceedingly rare person who made the leap, abandoning the life of a mental health professional to wrestle with his identity, unearth hidden desires, and seek spiritual meaning. He then shared what he had learned, emerging as a creative erotic healer, a maverick Buddhist, and a generous teacher drawn to probe the mysteries of mortality even as he approached his own demise.

Looking back, there are a few clues tied to sex and death that hint at the radical direction his life would eventually take. Schwartzberg’s Jewish parents joined the postwar exodus from Brooklyn for the fledgling Long Island suburbs a year after his birth in 1958. The town was a mix of middle-class Protestants, Catholics and Jews. His father was in the building supply business, and his mother – a legal secretary – hired a decorator who filled their modest split-level home with modern art and French provincial furniture.

While his brother Mark, two years older, was outside playing ball, the younger Schwartzberg would reposition his single bed, two dressers and desk, then stand on the threshold with his hands on his hips to judge the aesthetics of the new arrangement. Two or three times a day, he would envision changing into a fabulous new dress and matching hairdo. He adopted a gait to accommodate imaginary high heels and struck dramatic poses. ‘In pictures, I look like I’m imitating the German supermodel Veruschka,’ he said.

His parents tolerated what he calls his ‘incredibly faggy behaviour’, but it was less accepted outside the home. In first grade, he was scolded for his odd way of walking. Until the fifth or sixth grades, he delighted in all things feminine. The result was ‘shame, humiliation, and guilt. I was deeply homophobic. It was all very fucked up. Today I would have tracked as trans.’

College gave Schwartzberg a chance to channel his childhood love of outfits and personas

Strong believers in education and culture, his parents took their two sons to museums and Broadway shows, feeding Steve’s passion for entertainment and intellectual pursuits. Then in 1972, when Steve was 14, and in the throes of a puberty that was making him a man, Mark sickened and was hospitalised for three months.

His parents kept the diagnosis of leukaemia secret from Steve, telling only a few close friends and their rabbi as Mark endured brutal chemotherapy. When Mark finally came home in the summer of 1973 – gaunt and weak – he, Steve and their mother played board games until his strength gave out and he was hospitalised again. When the call came soon after that Mark had died, their mother stayed behind while their father took Steve to see the body – his vivid first encounter with death.

After the funeral, the family sat shiva for the required seven days, but Steve felt little solace in the ritual. ‘I developed an antipathy toward Reform Judaism, the way a teenager can reject his traditions,’ he said. His parents, once active in the local temple, also abandoned their faith. Saying Mark’s name became taboo. ‘They just couldn’t evoke his presence,’ he said. Though his parents would act normal during social occasions, with his mother adopting a ‘happy, perky, superficial’ mask, a stilted quality settled over the home that felt as if no one could get enough oxygen.

College gave Schwartzberg a chance to escape that stultifying atmosphere and to channel his childhood love of outfits and personas. At the University of Pennsylvania, he joined an acting group called the Mask and Wig Club. His quick wit later prompted him to partner with others to create the comedy troupe Mixed Nuts. They rode the growing popularity of the comedy club circuit in the early 1980s, opening for acts like Jay Leno and Jerry Seinfeld that were just breaking big.

One night he was called to a gay club, where he danced on the shiny bar amid the screaming throng

But he also lived a secret second life, hovering around bathrooms where men had sex, before finally overcoming his fear and shame to engage in quick and anonymous encounters. His study of psychology was little help in coming to terms with his sexuality, but literature provided welcome insight. Patricia Nell Warren’s novel The Front Runner (1974), the story of a gay coach who confronts and ultimately overcomes hatred and prejudice, was particularly affecting. ‘Wait a second,’ he realised, ‘I’m not sick. The ones who say I’m sick are the really sick ones.’

The 1980s were perilous times for a young gay man. AIDS ravaged urban gay and bisexual communities, killing more than 8,000 men in Philadelphia alone, creating ‘the epidemic’s bleak terrain of loss’, as Schwartzberg’s book A Crisis of Meaning: How Gay Men Are Making Sense of AIDS (1996) would later put it. He threw himself into mental health triage, counselling victims and their friends, and eventually running an AIDS support group.

To make ends meet, he took advantage of his lithe figure, black curls and love of the stage to deliver striptease telegrams. At Secretary Day parties, Schwartzberg would don the clothes of a construction worker, a security guard or a cop, then disrobe down to red Speedo briefs with the company’s name stitched on the crotch. One night he was called to a gay club, where he danced on the shiny bar amid the screaming throng. ‘I was intoxicated with my own sexual power,’ he said.

When he turned 27, he concluded that he was wasting his life. He left Philadelphia, and went to psychology graduate school in western Massachusetts. His goal was to be taken seriously. By his mid-30s, Dr Schwartzberg was on the faculty at McLean Hospital, the famed Harvard-affiliated mental institution outside Boston. He had started a private practice and thrown himself into a passionate but tumultuous relationship that didn’t last. His clinical research led to his 1996 book describing how some suffering gay men accepted the paradox of living while dying, achieving what he called ‘remarkable transformations’ amid ‘the anguish of meaninglessness that weighs others down, the vapour of grief that hangs in the air.’

As he sat on the beach in Provincetown in 2002, Schwartzberg had already taken a first halting step off his traditional career path. Three years before, he’d attended a workshop at a bed and breakfast in rural New Hampshire. The course was part of the Body Electric School founded in the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1980s by the ex-Jesuit Joseph Kramer. Amid the terror of the AIDS epidemic, Kramer pioneered a safe erotic-massage technique for men seeking a deeper connection with their bodies and sexuality. The organisation took its name from Walt Whitman’s stirring and homoerotic poem, ‘I Sing the Body Electric’ (1855).

At the workshop’s concluding exercise, Schwartzberg lay on a massage table as two participants stroked his body while lyrical music played, and the facilitator banged on a drum. After 20 minutes of deep breathing, he exhaled sharply, and that’s when he met Jesus. ‘He was loving and welcoming,’ Schwartzberg recalls. ‘He was sitting on a throne and there was heavenly music playing.’ The experience rocked the world of this Jewish secular-minded psychologist.

Schwartzberg signed up for more Body Electric workshops, eager to explore the power of his erotic energy far removed from bathroom groping or one-night stands. He was particularly drawn to sacred intimacy, a practice that encouraged touch between practitioner and client as an alternative to talk therapy. He quickly perceived that he was a natural. ‘I was a mediocre psychologist, but I was a gifted sex healer,’ he explained. ‘My touch was centred on the other person, not like a vampire, but to enhance the other’s experience.’

For a psychologist trained in a field where sex with a client was a career-killing move, this was a revelation. Yet he’d felt unsure how to incorporate this newfound gift – until that morning on the beach. After he heard the ‘inner megaphone’ to open his life, Schwartzberg returned to Cambridge and transferred $20,000 from a fortuitous investment into a separate bank account to cover the cost of his planned sabbatical. At first, he felt hesitant. But, three months later, with his sense of urgency undiminished, he closed his practice, took a leave of absence from the hospital, rented out his apartment and psychotherapy office, and moved in with a friend.

‘I was going to be a prostitute. At 45, I was going to become a sex worker’

He immediately sought the advice of a local Body Electric facilitator on how to overcome his fears of opening his own sacred intimate practice. ‘I’m a prostitute,’ the longtime instructor bluntly told him. ‘I could dress it up by saying it is heart-centred and I’m providing erotic guidance, but I have sex with people, and I collect their money.’

The candour was refreshing. ‘I was going to be a prostitute,’ he said. ‘At 45, I was going to become a sex worker. I had been too scared to do it when I was doing striptease, but now it was time.’ He was eager to plug into what he calls the archetype of the sacred prostitute. ‘I felt honoured to be called into the mythic cadre of sex healers.’

Schwartzberg began to work with clients wherever he was staying, drawing on his sense of theatre to experiment with role-playing methods like domination, submission, and bondage. He found these approaches could break deeply held societal prohibitions – sex with family members, the boss, or a cop – without causing harm while increasing self-knowledge. ‘We all fantasise about breaking taboos,’ he reflected, ‘and this is a safe way to explore the edges to find healing.’

Each session had its own flavour. One long-term client wanted Schwartzberg to be a ‘pervy psychologist’ who would move from talk to hot sex, illuminating his deep-seated anxieties around authority. Another sought to be a better kisser. Others simply wished to be held as they related painful secrets. ‘If someone wanted to be physically or verbally abused, I would find ways to interrupt the session to say: “You are a beautiful human being.”’

Schwartzberg also set out on journeys around the world, travelling from Europe to India to Myanmar, sometimes alone and other times with a companion. Back in the United States, he stayed with friends or house-sat, rarely needing a hotel and taking advantage of all-you-can eat breakfasts to carry him through the day. His savings, small book royalties, and sacred intimate earnings covered his modest expenses. He also developed ‘a very robust and satisfying erotic life’ that was both casual and open-hearted. He enjoyed lovers around the world, from rural Vermont to gay-friendly Amsterdam, with no intention of turning them into long-term relationships.

He also embarked on inner journeys. In the Peruvian Amazon, he spent 10 days with a shaman drinking doses of ayahuasca, a potent brew containing the psychedelic dimethyltryptamine, or DMT. On the final trip, Schwartzberg tapped into the consciousness of ants, feeling their way of being that mingled individual with group consciousness. The experience opened a door into an alternative universe where ego was just an illusion.

Later, during an all-night psychedelic session in the Utah desert, a guide challenged Schwartzberg’s deep, existential mistrust, traced to youthful isolation, the tragic death of his brother, an early sexual trauma, and the AIDS plague. ‘That insight landed. I stayed awake much of the night, dancing through the desert, saying: “I love my suffering. I love my suffering.”’ Simply recognising the source of his habitual unhappiness lessened its grip.

The insights came at a high cost. ‘Steve always had tons of anxiety and was self-questioning,’ one close friend recalls of that period. ‘He was also a huge entertainer, who struggled with his desire to be the centre of attention – a trait he felt was neurotic.’ Schwartzberg recalls succumbing to ‘a kind of pathetic despair that I had fended off all my life.’ Without a structured life of work, ‘there were no guardrails, nothing to stop me from slipping.’

Within a year of starting his nomadic life, he fell into depression. ‘I didn’t yet have the psychological underpinnings to be messing with these substances,’ he said of his psychedelic use. ‘I went into the underworld.’ He linked it to a traumatic sexual experience soon after his brother’s death; he will say only that it was ‘absolutely horrifying’.

In 2004, stoned on a marijuana-laced cookie, Schwartzberg found himself writhing on the floor of a hotel room near the Ganges. Two friends present could do little to help. ‘Uncle! You win!’ he shouted at something dark he connected to the trauma. ‘Then,’ he recalls, ‘I felt this energy gather in and around my anus and then it lifted up and out.’ He sat up clearheaded, thinking: ‘Despair doesn’t work.’ The despair, he realised, had been a plea for rescue from his internal anguish.

Schwartzberg hadn’t believed in exorcism, but the encounter exposed him to the power of the unseen world. ‘It took another year or year and a half to purge myself completely, but I’ve never gone back to despair.’

‘There were no mantras, no vibrating bells. You just anchored yourself in your breath and noticed your stupid thoughts over and over again’

He drew on the Talmudic tale of four rabbis who enter the Garden of Eden: ‘One dies, one goes crazy, one can’t leave, and only one is able to navigate the ultimate truth and the relative world.’ He was determined to be the fourth rabbi. Soon after his experience in India, he committed to a daily meditation practice to work his way out of the mental and spiritual thicket in which he felt entangled.

Over the years, Schwartzberg had paid occasional visits to a Buddhist meditation group in Cambridge, MA. ‘There were no mantras, no visualisations, no vibrating bells. You just anchored yourself in your breath and noticed your stupid thoughts over and over again. The thoughts that you don’t pay attention to, but which probably cause you a lot of suffering – “You are such an idiot!” or “You are so great!” Or both, or “Oh, shut up.”’

At first, he couldn’t sit alone for more than five minutes without a paralysing fear that he would plunge into depression or resurface some old trauma. Yet, with his natural aversion to authority, he was reluctant to seek out a teacher. ‘I’m a rebellious student, and most gurus I’d met just fed their ego,’ he said.

Yet by 2007, nearing 50, he felt experienced enough to sign up for a silent retreat at the Insight Meditation Society in central Massachusetts. There he trained in the Theravada tradition, centred on meditation and close attention to experience as it unfolds, with Joseph Goldstein, the society’s co-founder. With Goldstein’s patient guidance, Schwartzberg learned to sit, focus on the breath, and detach from the busy mind with its constant demands, desires and addictions. He also learned to repeat a series of phrases such as ‘May I be safe,’ ‘May I be happy,’ and ‘May I be healthy,’ extending these affirmations to loved ones and, eventually, all beings. The practice – lovingkindness or metta meditation – is designed to expand one’s sense of empathy and connection.

Goldstein sensed Schwartzberg’s inner struggles. ‘My impression was that Steve was trying to reconcile different sides of himself,’ he says now. He encouraged Schwartzberg to give up psychedelic journeys for the more arduous but enduring benefits of meditation. And though the two didn’t discuss his erotic work, Goldstein offered a gentle caution, quoting a Burmese teacher, whose views were summed up with one simple phrase: ‘Lust cracks the brain.’

Schwartzberg did ease off his psychoactive drug use, but he expanded his erotic exploration. In 2005, he had joined the Body Electric faculty and soon found himself teaching the same workshop – Celebrating the Body Erotic – that had prompted his 1999 encounter with Jesus. By 2008, he took the radical step of integrating erotic and contemplative practices in a novel way. With his friend and colleague Michael Cohen, he launched an intensive week-long course for men at the Bodhi Manda Zen Center, tucked away in a remote valley of New Mexico and led by an abbess long supportive of the Body Electric School. They dubbed it ‘Touching the Heart of Stillness’.

A morning bell called silent participants to the tatami-mat-covered Sutra Hall for hours of sitting and mindful walking. ‘Imagine your thoughts are trains leaving the station. Don’t get on the train,’ Schwartzberg would say. After a simple vegetarian lunch, participants adjourned to the zendo, a meeting room in an adjacent adobe building. Facilitators then broke the silence, providing instructions for randomly paired and group erotic touch and massage exercises, though with strict boundaries that precluded kissing or penetration. The purpose was to keep one’s body in the mix after long solo sits, and to experience the power of pleasure in connecting with oneself and others.

After dinner, Steve lectured on Theravada themes, telling stories drawing on Jewish sages as well as Christian mystics, and taking questions – what in Buddhist circles is known as a dharma talk. Then the men broke up into small groups, allowing individuals to compare notes on the day’s insights and challenges, before resuming silence until the next afternoon.

Schwartzberg liked to say there was no other workshop like it on the planet, and even old hands felt its edginess. ‘I was scared shitless,’ says Tom Kovach, Body Electric’s executive director, when he took the course for the first time. ‘But Steve is like a maestro who brings the orchestra together so that each instrument plays beautiful music.’ He also was notorious for dictating elaborate staging, and leading late-night staff meetings that often left his assistants exhausted.

One of his lasting realisations was that everything is fleeting, whether a feeling, a thought, or a life

All the while, Schwartzberg continued his peripatetic life as a queer modern-day mendicant with means – meditating, travelling, living with friends, working with intimate clients, and writing occasional pieces for The Huffington Post. At the Insight Meditation Society and centres in California, Nepal and India, he lengthened his silent sits from a few days to 10 days, then a month, and eventually three months.

As he submitted to a practice meant to calm the mind, minor inconveniences could flare into crises. When his glasses broke, ‘I freaked out.’ At an idyllic California retreat, he watched the bananas dwindle; when the man in front of him took the last one, he was inwardly incensed.

Such moments revealed the power of the ceaseless, disconnected thoughts coursing through him and the rigour required to notice, accept, and move beyond them. Over time, he embraced the Buddhist notion that the ego and the self – so central to his Western training as a psychologist – were delusions, and that interpersonal strife was self-hatred directed outward. For six months, he and Cohen attempted ‘right speech’, avoiding gossip or malice. ‘No dissing other people, no lying,’ Schwartzberg said. ‘It’s really hard – and really boring.’

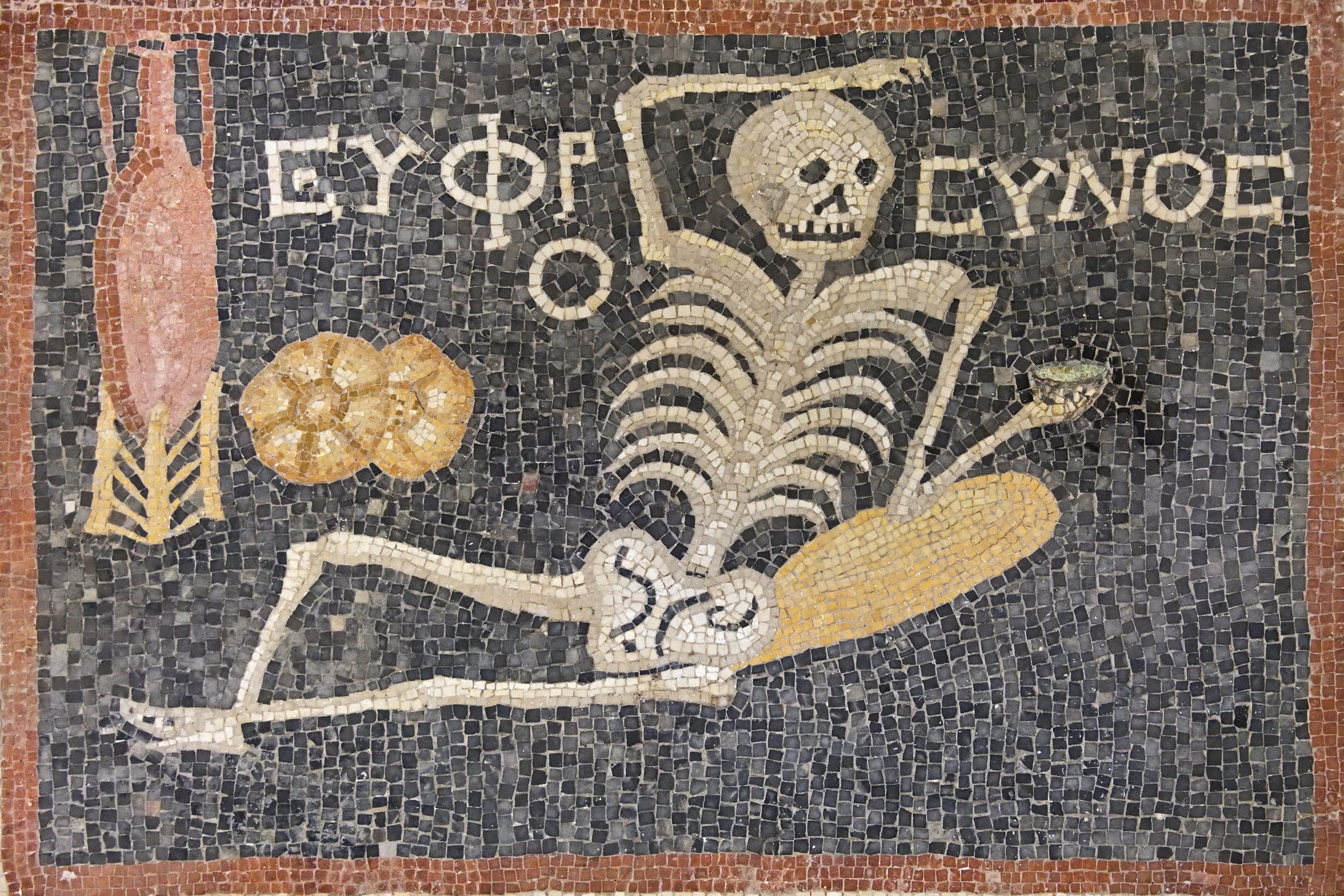

One of his lasting realisations was the central Buddhist teaching that everything is fleeting, whether a feeling, a thought, or a life. This led him to explore his notions of mortality shaped by his brother’s death and by a generation of gay men. He took a Buddhist-oriented course on death and dying but was underwhelmed. ‘It felt too academic.’

With characteristic chutzpah, he decided he could do better, and designed his own workshop, a virtual seminar on how to approach the thought of one’s death ‘with more conscious ease’. He advertised ‘Unmasking Mortality: A Yearlong Practice in Living and Dying’ at the start of 2020.

Weeks later, the COVID-19 pandemic swept the planet. Fifty people immediately signed up for the Zoom course he could teach from an office at his housesitting gig outside Boston. Had he known then what he would soon learn, ‘I would have created a course on origami, or maybe how to take pretty nature pictures.’

On Memorial Day weekend in 2021, nine months into his mortality course, Schwartzberg went to a friend’s home for dinner. An energetic 62, he retained a wiry frame, cultivated abstemious habits, and had long enjoyed good health. That spring, however, he developed a wracking cough. His concerned dinner companion slipped a pulse oximeter on his finger. ‘I wasn’t concerned when it read 87 per cent – it seemed like getting a B+,’ Schwartzberg said. But when he informed his doctor, he was told not just to go to the emergency room, but to pack a bag.

Admitted to the hospital, other puzzling and debilitating symptoms quickly arose. Soon, he could not get out of bed unaided. ‘A few days later, out of the blue, I was told: “You have cancer,”’ he recalled. The diagnosis was adenocarcinoma, and the malignant tumours infesting his lungs had already spread to a dozen other parts of his body, including his brain. There was no cure. ‘I was told to put my affairs in order.’ Mortality had indeed unmasked itself in a sudden and personal way.

‘The story I had told myself my whole life is that I never got past stage one, that I was stuck in mistrust’

Schwartzberg had absorbed the Buddhist teaching that ageing, sickness and death were not harbingers of suffering but divine dispatches of spiritual insight. When Goldstein, his meditation mentor, sent an email noting that his terminal diagnosis marked a visceral encounter with one of these ‘heavenly messengers’, Schwartzberg bridled. ‘I was furious,’ he said. ‘I wasn’t ready to hear it.’ He found himself overwhelmed, anxious, and distressed. ‘I had overestimated my ability to embrace death as an abstract idea,’ he recalled. ‘I continued to carry the idea that I was exempt.’

After three weeks in the hospital, he was discharged back to his temporary home outside Boston. One night soon after, he awoke to the sound of his own voice. ‘I trust. I trust. I don’t know what the outcome is going to be, but I trust.’ He recalled that the psychoanalyst Erik Erikson called trusting the first stage of individual growth. ‘And the story I had told myself my whole life is that I never got past stage one, that I was stuck in mistrust.’

But the utterance shattered the story that had made him dance in the Utah desert, and intense apprehension gave way to a level of acceptance. He found confirmation in a poem he came across in The New Yorker by Jane Mead, who’d died from cancer in 2019. ‘I wonder if I will miss the moss/after I fly off as much as I miss it now/just thinking about leaving,’ she wrote. ‘Yeah, I will have flown off,’ he thought, ‘but I don’t think I’m going to miss it.’

Schwartzberg was slated to undergo his first round of chemotherapy late that summer, and his physicians warned that the toxic chemicals could slow but not halt the cancer’s spread. Then, on the Friday night before the treatment was due to begin, his phone rang.

‘Guess what?’ said his oncologist, ‘you just won the golden ticket.’ The ticket was a new drug designed to combat his illness, but effective only with a particular genetic mutation that, fortuitously, was part of Schwartzberg’s DNA. All he had to do was swallow a single pill daily. ‘Within a week, I was already feeling better, and within a couple of months I was off oxygen,’ he recalled. ‘Within six weeks, I could walk up the stairs again.’

That recovery came with a caveat. The pill would work for a limited period of unknown duration. Yet with only relatively minor side effects, the drug gave back Schwartzberg most of his capacities. This sudden reprieve offered him a second chance. He embarked on a brief but passionate relationship, officiated at a wedding in a white linen suit, and offered online weekly meditation sessions. He also relaunched his ‘Heart of Stillness’ workshop as well as another, called ‘Erotic Temple’, made up of a series of interconnected rituals.

He rejected the mantle of teacher, much less guru, encouraging others to find their own path

Schwartzberg also softened toward his parents. He had always been a dutiful son, though somewhat at a remove since his brother’s death. When his father grew ill, their mutual looming mortality brought them together. ‘My father and I had had a contentious relationship, and I got very clean with him,’ he told me. ‘I was there with him on Zoom when he died, and ushered him into the transition.’ Schwartzberg also came closer to accepting his still-vital mother who loved him ‘deeply, insanely, pathologically, and beautifully’.

During this period following his diagnosis, colleagues noticed a profound change. ‘He was a different and fuller teacher with great kindness and compassion,’ Goldstein notes, adding that Schwartzberg ‘had a bit of a hard edge that softened; he felt, in some way, more integrated.’

Amid this change, Schwartzberg attracted eager students to his Zoom meditations and talks, but rejected the mantle of teacher, much less guru, encouraging others to find their own path. ‘I don’t recommend that anyone sell their house, quit their job, travel through India,’ he explained. The real work is for each person to find the trapdoor that leads into a deeper state of consciousness. That means subverting the ego, an entity ‘deputised to keep us safe and in control’.

By the spring of 2025, the daily pill’s magic had dwindled. While travelling to India’s holy city of Varanasi to visit the burning pyres of the Hindu dead, he grew suddenly ill. He returned to Boston with a swollen brain that destroyed the vision in his left eye. Scans showed his condition was worsening. The unwelcome news placed him on a seesaw between anxiety and acceptance. ‘I was really thrown when an MRI wasn’t posted, and the doctors didn’t respond to my calls,’ he said. ‘I can still get irritable with people.’ But he just as quickly grasped that the agitation stemmed from the ‘delusional idea that I’m in charge of all of this’.

Living in a rented home in the Boston suburb of Brookline, close to his medical team, Schwartzberg agreed in the summer to their recommendation that he undergo chemotherapy, surprising himself by his intense desire to remain alive. He also agreed to set aside many precious mid-afternoon hours – when his fading energy was generally at its peak – to discuss his life and lessons with me.

‘There is no escape,’ he told me, sitting on the porch one August afternoon. His frame, always thin, bordered on gaunt, and his head was newly shaved for the chemotherapy he had recently begun. ‘We live as if our own dying is the only thing that is not true. Yet it is true. I don’t have endless time.’

One concern was that he would lose his capacity to speak or think. ‘Who is not attached to their thinking? It’s not like I don’t get gripped by the fear of dying. There can be a little bit of panic about whether there will be pain. But it is all going to end.’ We all are coming and going, he explained.

Dying, too, is a spiritual and existential coming-of-age. ‘Wow, my consciousness gonads are dropping!’

He’d discovered that he could hold the truth of his mortality in a non-morbid way, quoting Stephen Jenkinson, author of Die Wise (2015), who said that dying is not scary – what’s scary is dying in a death-phobic culture. ‘The fact that I get to do it this way is cool,’ he added, acknowledging the circle of friends making it possible to experience a more conscious dying process. ‘I’m learning a lot, and it’s very moving for me to share it with others.’

The process, to Schwartzberg, harked back to his teenage years and the struggles of puberty, lying latent for the conditions to set it off. Dying, too, is a spiritual and existential coming-of-age. ‘Wow, my consciousness gonads are dropping!’ he wrote on his Caring Bridge page in June. This second puberty came with irritability and sadness but, mostly, he felt joy. ‘I never thought that would be part of my orbiting closer to death.’

What comes next? ‘Death may be magnificent beyond comprehension; the gateway might be a beautiful human experience, but nobody has come back.’ As he neared the end, he wanted to be reminded by others that he was dying. ‘I wonder if I will struggle to breathe, or forget everything I’ve learned.’

This was quintessential Schwartzberg; painfully aware that all his hard-won knowledge might be swept away in a moment, yet refusing to entertain regret. In his final months, he only intensified his efforts to impart what he could before death silenced his increasingly hoarse voice.

On 8 December – celebrated by Buddhists as the day the Buddha was enlightened – Schwartzberg began one final meditation at his home, slipping gently into a morphine-induced sleep. Two days later, he drew his last breath. A small group of friends tenderly washed the body and dressed it in the white linen suit. The shrouded corpse was laid to rest in a cemetery on Cape Cod, a dozen miles from Captain Jack’s Wharf.

Near the end of his boundary-breaking life, Schwartzberg offered one compelling lesson: that ‘there is something other than me, from which the self emerges and is intertwined.’ He came to trust this nameless something to provide solid ground – and a measure of joy – amid the passing bouts of disorientation and fear. Sitting on his porch in August, he pauses, squinting through the tree branches shading him from the fierce end-of-summer sun. ‘I can’t tell anybody else how to do it,’ he said finally, ‘but I can say this is possible.’