When strangers ask about my disability, why I move around with crutches and a wheelchair, I tell them I used to be a pole dancer. The other dancers at the joint were jealous of my exquisite pole-dancing skills and greased the pole before I went up on it. And that was how I slipped and broke my back.

The truth is sombre. I contracted polio as a child and my legs withered. My parents, Somali nomads in the deserts of Wajir County, in the northeastern region of Kenya, placed me in town at a facility for children with disabilities; I was unable to follow them around with their herds of camels and goats as they sought pasture. It was at this facility that Inge found me. A tall German woman with bright-red lipstick and big round glasses, whose greyish-tinted bobbed hair danced around her jaw, Inge became my Mommy. There was no paperwork, just an agreement with my Somali parents that she would raise me, take me to school, and ensure I remained Muslim till I was 18.

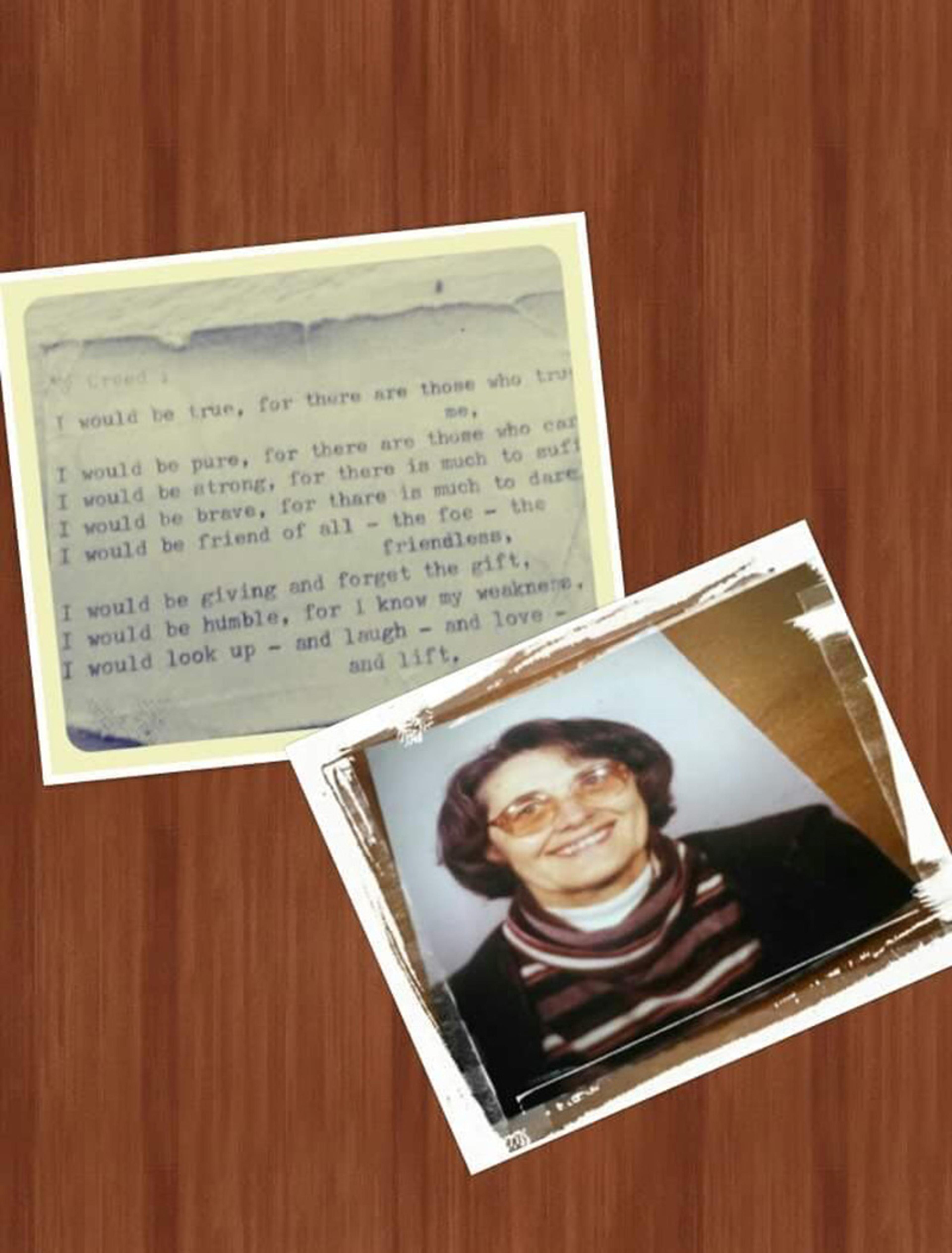

An undated photo of Mommy Inge, carried by Sauda in her purse

She adopted three of us at the facility, and with my new brother and sister, the four of us moved to Meru, more than 300 km away. Meru was green and forested, unlike Wajir. It had many types of fruits, from pears to mangoes to apples, unlike the pawpaws and watermelons that were our only options in Wajir. We had a big compound where we played in the mud and kept chickens and rabbits, a dog and a cat that were sworn enemies, and two tortoises whose loud mating shred through all decorum.

Mommy wanted me to learn how to depend on myself inasmuch as I used crutches. If I was walking anywhere and fell down, she would ask me to identify the reason why. If we were along a road and I tripped, passersby would naturally come to my aid. Mommy would patiently wait for them to be done before placing me back exactly as I fell, then ask me to find a way to get back up on my own. She would insist I do this no matter how much I cried and protested. One Sunday, when I was around 12 and in seventh grade, the four of us were seated outside under an umbrella awning, Mommy doing her crosswords as usual, she asked me to go to the kitchen and fix her a cup of iced coffee. I was livid. Of the three siblings, I was the only one using crutches and I needed my hands to balance on them. In the kitchen, I had to fetch the tray of ice and a tub of ice cream from the fridge, then move over to the coffee maker to mix the ingredients. Needless to say, most of what I made spilled and trailed in my wake as I toddled back outside. Mommy took the cup from me and said she would fix herself a proper cup. She only wanted me to try. That was the first time I carried a beverage while using my crutches and I’ve been doing so ever since. People ask me how I swim so well, and I tell them how Mommy would throw a coin at the bottom of a swimming pool and send me diving all the way to the bottom to retrieve it.

When I was 18 and in my final year of secondary education, at a boarding school, a teacher called me to the staffroom. Our neighbour Nana had come to fetch me because Mommy was extremely ill. I walked into her hospital room in Meru and saw her, tubed up and swollen, and said that was not my Mommy. I walked out. That was the last time I saw her. The hospital wanted to transfer her to Nairobi, 200 km away, for better treatment. The chopper required to fly her out couldn’t land at the stadium in Meru because it lacked floodlights. The next best option was to use the airstrip in Nanyuki town, about 70 km away. The hospital in Meru had no ambulance so they asked the hospital at Nanyuki. The hospital in Nanyuki had an ambulance but no driver. In the hassle of arranging a driver for their ambulance, Mommy passed away.

The years that followed became a blur, as we waited to see which family was going to take us in

We were at home in Meru waiting when Nana came with Mommy’s friends to tell us she was gone. My mind was not on death at all, so I asked if she meant Mommy was now gone to Nairobi. She had to state outright that she was dead. I used to pray a lot before that day. At school, I ensured I prayed at 5 pm, believing my prayer would reach God before anyone else’s that way. When Mommy was still hospitalised, my sister asked me if she was going to be alright and I told her yes because I was certain God wouldn’t allow anything bad to happen to her. I stopped praying after being told Mommy had died. I stopped believing in God for letting her die. The only member of our family who seemed to have sensed her death was our dog King, a German shepherd. He kept lying on my shoe as we sat at home waiting, and when Nana came to tell us the news and drive us to hospital, King jumped on the driver’s seat and refused to get out. Forcibly dragged out, he crawled and edged himself against the wheels, whimpering.

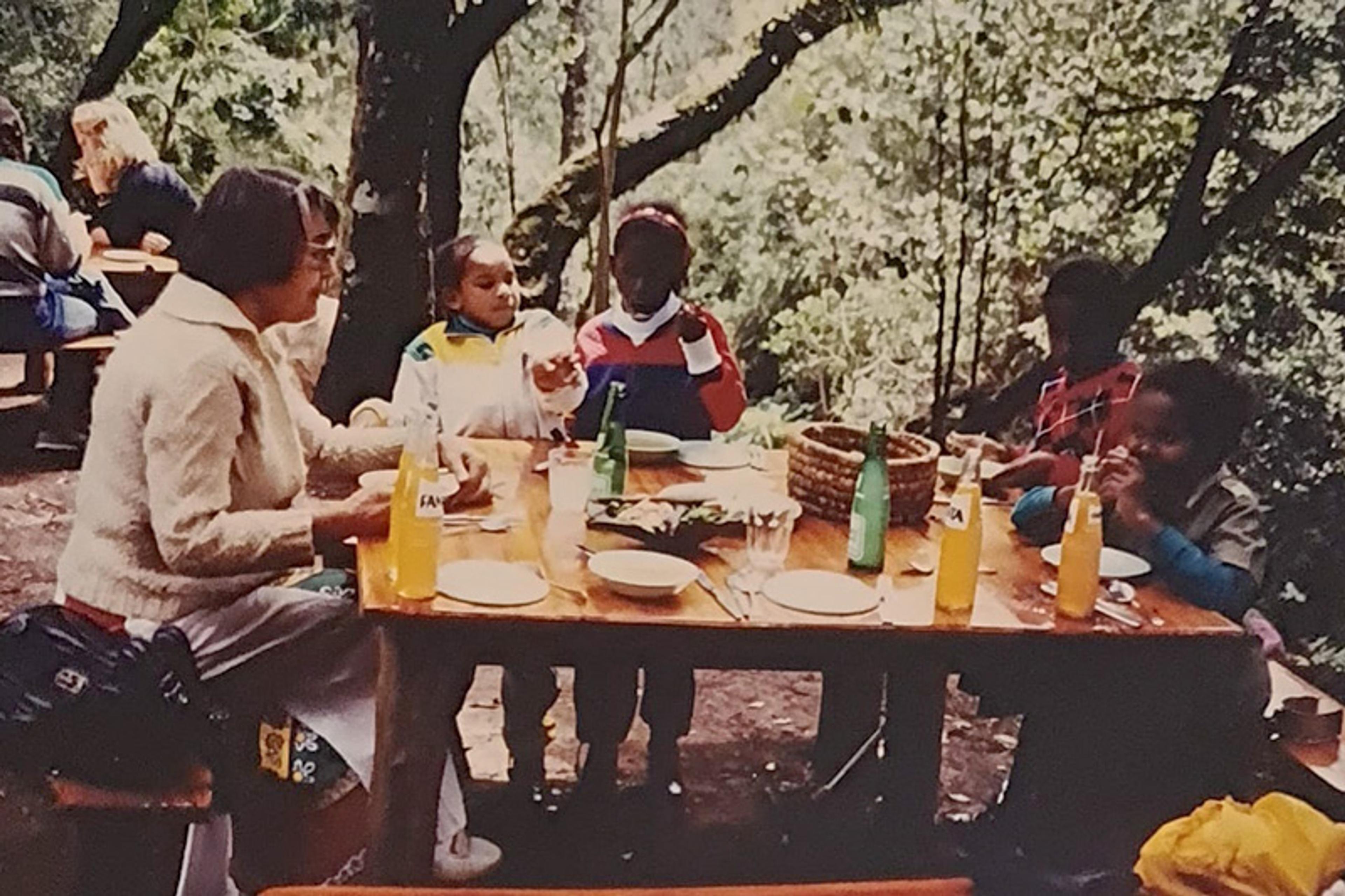

Inge, Sauda and the family c1993 at Kentrout, Timau in Meru County, Kenya.

I never saw Mommy’s body. She was cremated when I had gone back to school to do my final-year KCSE tests, which I was too numb to even read for. There was no memorial. The years that followed became a blur, as we waited to see which family was going to take us in. Even though I was 18, I still needed support. In Africa, at that age you’re still a child. Eventually, the three of us joined another family of eight children in Kitale in the Rift Valley province, nearly 500 km away. I was now part of a larger family with lots of new people and too many moving pieces. There was no longer a clear plan for my life, now that I was done with secondary school. But Mommy had taught me to be strong, to find my way.

Knowing no one was planning for my future, I called my biological brother and said I was going to attend Africa Nazarene University in Nairobi and needed school fees. My biological father sold his camels to pay the first instalment of my tuition. I needed a place to stay in Nairobi, so I picked up my suitcase and moved in with my extended Somali family in Lang’ata Estate. Somali culture is accommodating like that: I didn’t have to ask permission to be hosted. I started using a matatu (share taxi) to go to campus, knowing there was no one I could rely on to drop me off and pick me up. Matatu conductors were fascinated to see me walking around with crutches. ‘Hey there, beautiful! You shouldn’t struggle this way when you are so pretty,’ they would shout. They eagerly blocked freeways for me to cross and fought for me to board their matatu. I was guaranteed the front seat; anyone already seated there would be asked to move because ‘Sauda has arrived.’ The touts would lift in my legs and crutches once I was inside.

She nurtured and endowed me with the values and work ethic I rely on to navigate life

Upon graduation with a degree in mass communication, I did a few internships before landing a customer service job at a telecom company. With the little money I had, I secretly rented a small apartment for myself and moved out of my relatives’ home. They called me the next day, as I knew they would, reprimanding me.

People struggle to live by themselves not because of their disability but because they haven’t been trained on how to live on their own. This can be as simple as knowing how to pay your bills on time. In my empty house, with nothing more than a bed, a mattress and curtains, the only other machine besides my phone being the microwave, I reconciled with God. I acknowledged that Mommy dying had nothing to do with a divine plan but her succumbing to a severe sickness. I told people who stated I was on crutches because of God’s will that, actually, I was on crutches because I was never vaccinated for polio. It was that simple.

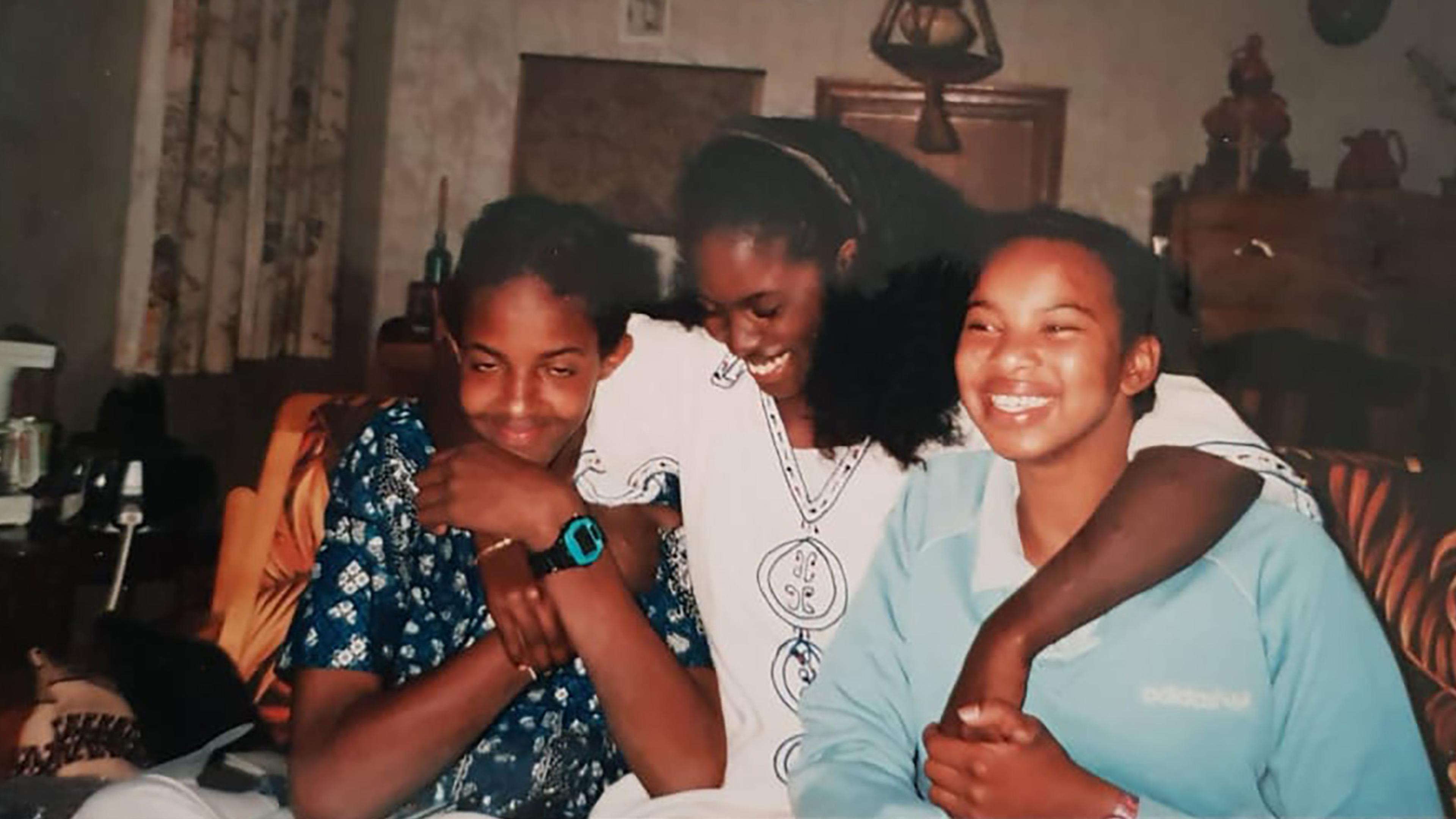

I have known three mothers in my life, but when I say Mommy, I mean my German mother. She nurtured and endowed me with the values and work ethic I rely on to navigate life. I met my other mother in Kitale when I was already a young adult, when I no longer needed her to make sense of life. I call my biological Somali mother ‘mom’ out of respect. She let me go and live and get to know my actual Mommy. My Somali mother visited me once in secondary school. It was her first time meeting me again after we parted ways in Wajir. She kept crying and hugging me, touching my hair and saying my name, but I felt nothing other than guilt that I felt nothing. Movies had taught me that blood was thicker than water, that any adopted child would be swept by a tide of emotions upon meeting their real parent, but the movies were wrong. Relationships you build are more solid. Blood relatives can treat you badly but you are stuck with them. You have more control over relationships you build. You can decide on its construction, how close or how far you need them to be. And if a relationship stops working, you can easily move on. I now have 11 siblings whom I’m very close to without us being related by blood. I am grateful to God for placing the right people in my life who have loved me and become family.

Sauda on World Disability Day, 3 December 2025.

I’m back to praying now. I pray for peace of mind and heart, for financial security, for a roof over my head. I want to travel more. I also pray for strength to walk away when a relationship is no longer working.