In the biblical story of Job, the man who loses everything sits slumped on an ash-heap, wailing in anguish. His friends try to comfort him, and when they finish, he roars: ‘Will your long-winded speeches never end!’ – calling them ‘miserable comforters, all of you.’

From the ash-heap, it’s easy to be judgmental. In her memoir The Bright Hour (2017), about her two years of cancer, Nina Riggs imagines revenge greeting cards for people she calls the ‘casserole bitches’. One reads: ‘Thoughts and prayers are great, but Ativan and pot are better,’ and another: ‘Thank you for the flowers. I hope they die before I do.’ Her anger targets those who flit in and out of our sickrooms while we stay stuck, but beneath it all are needs and fears so primal, so unfathomably deep, no one can fill them.

When I was ill, I understood Job’s rage. Now I understand the helplessness of his comforters.

I arrived in London with my husband in 2012, the summer of the Olympics, with an undetected tumour in my right breast. A year later, the news from a required NHS (National Health Service) mammogram torched my life. I’m a private person, so I didn’t want to share my diagnosis with colleagues, friends or even family. But when I took a leave of absence from work at the university, news spread. When I lost weight and had drains coming out of me from my surgeries, people knew. I needed family to come and take care of me, so more people knew. Worst of all, I had to tell my children, who were just starting their lives in college. When they found out, they tried to comfort me, each in their own way.

We lived on the top floors of a house overlooking Hampstead Heath, and my first year felt like being flung into a fairytale, portal to the settings of my favourite books from childhood. I saw Beatrix Potter’s cottage in the painted doorways on Well Walk and imagined the Little Princess’s room through the lit window of a pub, the fire crackling in the hearth. I envisioned Narnia in the streetlamps glowing in the evening fog as I walked up the hill to our flat.

Once I got sick, I was in and out of hospitals and the door to that life slammed shut. As my world narrowed, other people’s reactions blazed brighter – like headlights igniting a dark room. Everyone knew my business. And worse, I depended on them.

But I also cringed at their fear of my illness. Job experienced this too, and said to his friends: ‘You see something dreadful and are afraid.’ Job was perfectly innocent, as many of us are when tragedy strikes. Yet, his friends insisted he must have done something wrong to bring on such misfortune. Strangers and friends alike used me as a cancer predictor for themselves, peppering me with questions: did I do mammograms? Was it in my family? Did I smoke at some point, do drugs, take hormones? One woman looked at my breasts and said: ‘Yours are much bigger than mine, that explains it.’

Survivors also lived in fear. One fellow patient I met at the support centre said: ‘You’ll never feel safe again.’ She had been in remission for seven years, but the PTSD was so severe she was sure she’d be on anti-anxiety meds for the rest of her life. A distant relative who was dying said barely audibly in my ear: ‘Even if you think you are done, it will come back.’

Some denied tragedy altogether. At one support group I went to, some members attended every march, race and picnic. They wore pink ribbons, ate rose-iced cookies, and carried the tote bags (‘Cancer is a word, not a sentence’). One woman told me she and a band of other survivors didn’t get reconstruction, but instead tattooed flowers over their scars. A young woman talked about the gifts of cancer, from gratitude to self-love to knowing who you could count on – the best thing that ever happened to her.

Maybe it was ungrateful, but I didn’t have the emotional slack to be generous

Some of these deniers tried to inflate me with stories of their friends. One had stage 4 cancer but was now ‘fabulous!’ Another ‘runs her own importing business and just had her fourth child!’ Others said: ‘I know you’ll be fine.’ Who were they, Nostradamus? They shook their pompoms through my pain. Their energy felt manic compared to my own depressive bog.

Then the soldiers of God weighed in, telling me they had their church on a rotation praying for me, or they had me in mind when they recited the Jewish prayer for the sick on Shabbat. If I had any good news, I knew who to thank.

People also had medical advice. Many felt erasing cancer could be as simple as using mushroom tinctures or going macrobiotic. There must be something I could do, they urgently let me know in pinging texts and long-winded emails. My response to these helpers was over the top. I tossed the grocery-store flowers from my department at work into the trash when the note they sent with them was a generic Get Well card that featured a puppy and was signed by the administrative assistant. Maybe it was ungrateful, but I didn’t have the emotional slack to be generous.

Underneath that irritation was something deeper – a sense of defectiveness I couldn’t shake. Lying in bed with four drains next to me, my constant companions, I said ‘I’m so sorry’ to my husband, ‘I know I’m ruining our lives.’ He came over and collapsed on the bed, putting his hand over the drains and me – our new form of cuddling. My body had failed, malfunctioned, mutated, fallen prey to something, like falling for a scam artist. Those healthy people did something right, but I was the weak link, ruining my children’s lives, watching my husband shrink from the exuberant, resilient man I knew to a retreating, fragile figure.

As my disappointment fermented, I grew teary eyed with gratitude for those who made me feel heard and seen. Sometimes, I thought I’d burst with my feeling of indebtedness to them.

My husband, Mr Contingency Plan, dealt with uncertainty by going down the path of possible future disasters. He was like a survivalist preparing for emotional apocalypse. Whenever we went camping, the kids and I called him troop leader behind his back. He built roaring fires, put up a tent in the rain, cooked crispy bacon with eggs, and heated up canned apricots like a short-order cook. And when we went backpacking, he was always good with any bear situation.

After the diagnosis, one morning I found this handwritten note after he’d left for work:

To Do Rules

(THINGS WE KNOW)

1. It’s a small problem, we can manage it

2. I love you

3. Go to cancer center (take a minicab!!)

Take advantage of their services

Speak to nurse Lottie

4. Call HR, find out rules, procedures, rights

5. Call your mom. Have her come asap

6. You deserve support

I was touched by this because I felt so fuzzy I couldn’t function. Having someone take over my scattered brain felt like salvation. I followed his commands. I also kept the note.

My mother took me shopping for new underwear because who doesn’t like new underwear?

My mother-in-law came and filled my water bottles, sizzled up steaks, and watched melodramas from the 1940s with me. I sometimes forgot I had cancer since we would have done the same if I wasn’t sick. She offered to sleep over in a chair the night after my first surgery. She stayed for 10 days and then called for months after to check on how I was doing.

Many others assumed that, since the good scan, I was done. My mother took me shopping for new underwear because who doesn’t like new underwear? She made my favourite meals from childhood: lasagna and roasted lemon chicken.

My cousin walked up our stairs holding a fancy box of chocolatey things. After my fourth surgery, she presented a piece of cheesecake with blueberry compote from a fancy London restaurant. She was calm and I believed in her calm.

My new department sent a glorious fruit bouquet (my husband tipped them off that I didn’t like to get flowers during this time as they made me think of funerals). Magical to have mango every day for a week in the non-tropical island of England. Everyone wrote a message in a giant card, and their voices rang out funny and sweet with inside jokes, bringing me back into the fold.

My neighbour Joan, who was a therapist, hand-delivered a card with little fragments of minerals glued on, and she wrote: ‘Go from strength to strength.’ My college roommate sent me a book of weekend trips to take all over Europe inscribed with: ‘Something to look forward to.’ I paged through the three-day holidays, imagining myself healthy.

My son wrote before my first surgery: ‘If this whole thing can just end Thursday and you can spend the rest of your entire life dealing with nothing this big again, I won’t hold a grudge against the universe.’ My daughter penned an ode to my old breasts with memories from when she was little and crushed up against them or sat near me in the bath.

After my surgery, when I got a little stronger, I descended the stairs, pushed open the wrought-iron gate, turned left, and entered a lane so narrow I could almost touch both sides with my elbows, then a left past George Orwell’s house and I entered the Heath. Through the misty rain, I made out the shady oval of the boating pond, a church steeple, and an English woman clad in wellies milling about with her ecstatic wet dogs.

The last time I was in this spot, my college roommate and I had watched firefighters running laps up and down the steep and slippery hill. One young recruit started off strong but, by the fourth time, he started flagging and, by the fifth, he stopped to vomit. When the other fit firefighters sailed past him, my roommate decided we should cheerlead him to the top. ‘Woo-hoo! You can do this!’ she yelled when he was halfway to the top. Perhaps he didn’t like that kind of thing. Maybe we’d embarrassed him. Who can know what another person needs at their crucial moments? But when I saw his face, I popped up to join her. ‘Almost there!’ He grinned through the last few footfalls and seemed grateful for the support.

They saw how great his suffering was. They sat on the ground with him for seven days and seven nights

Loving someone who is ill or struggling can be harder than being ill. I have been on both sides of the equation. Being the diseased person, I always had a running update of my situation whereas people outside of my body were forced to guess. Their imaginations engulfed them. I remember seeing my husband’s face after one of my surgeries – ecstatic relief on the edge of sobbing. I had simply counted backwards and fallen asleep, but he had spent eight hours in limbo.

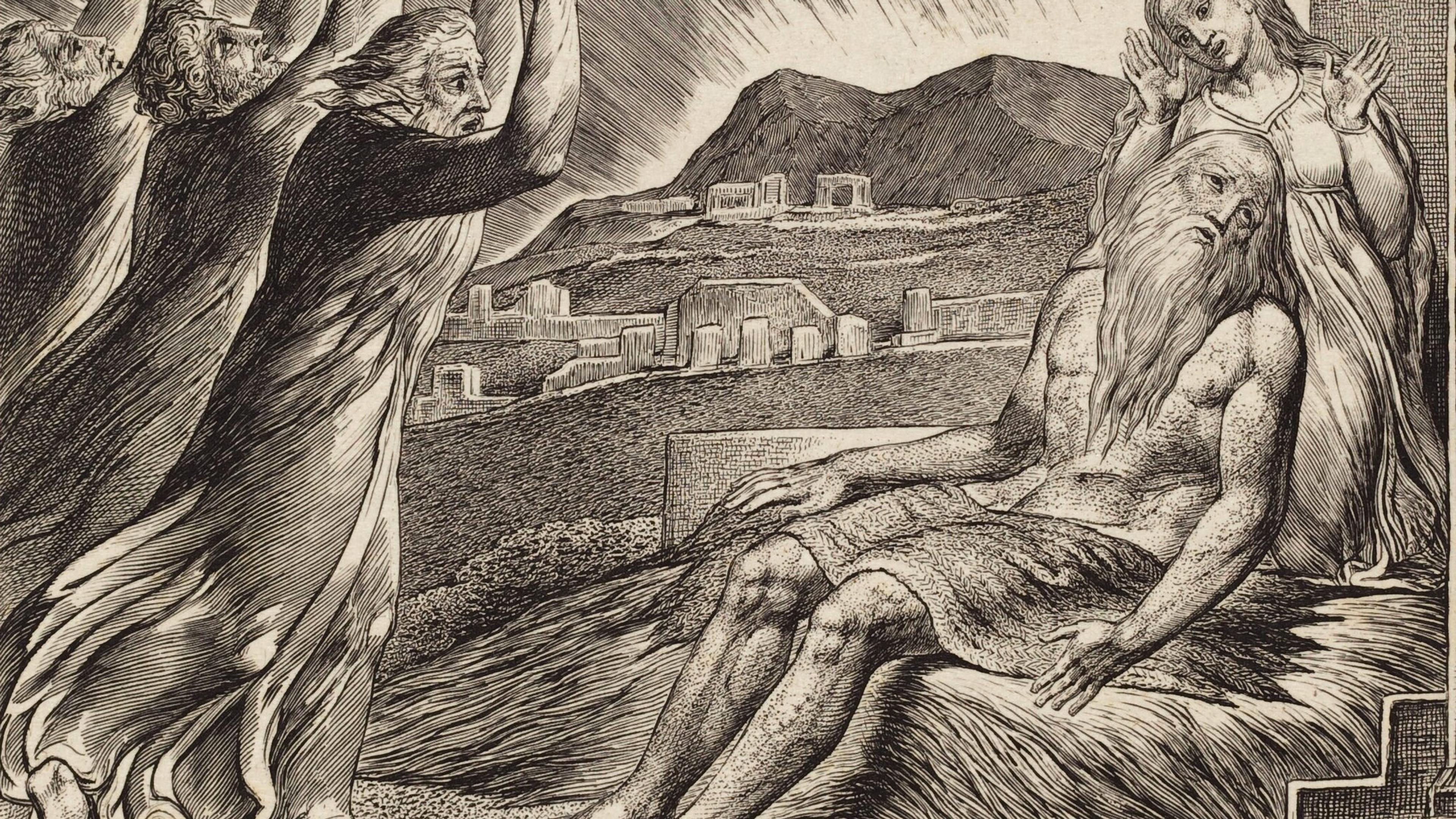

The story of Job is told over 25 chapters, but near the beginning it illustrates the essence of empathy. When Job’s three companions first arrive, ‘No one said a word to him, because they saw how great his suffering was. They sat on the ground with him for seven days and seven nights.’

My husband, who barely spoke to anyone about my cancer, still remembers the most comforting thing anyone said. When we were out of the woods, he confessed to a friend: ‘I don’t think I handled it well.’

His friend answered: ‘Who would?’