‘I remember the still mysterious association of Western music with greasy eggs in a diner on a Sunday morning…’

It’s a strange and yet nearly universal human experience: in an innocuous instant, a seemingly random memory sweeps over you. A cringe-inducing childhood moment; a bizarre dream you had all but forgotten; the ineffable sensation of being in a certain place with a certain person. It can even be the memory of a past thought. And then, as abruptly as it invaded your mind, it fades away – perhaps to resurface again later, or perhaps not.

These unpredictable mental moments sprinkled across a lifetime are the basis of the US artist Joe Brainard’s experimental and celebrated memoir I Remember (1970). To construct the work, Brainard recorded his memories as they arose into consciousness. Assembled in no obvious order and each beginning with the refrain ‘I remember’, the sentences gradually accumulate to build something resembling a three-dimensional person. Some of the experiences chronicled, such as running out of thoughts to exchange in a conversation and feeling stuck, feel near universal. Other recurring themes, such as slices of Americana with sinister elements lingering just below the surface, however, hint at Brainard himself – a talented gay artist who grew up in Oklahoma in the 1940s and ’50s, and found success in New York City in the 1960s.

Gathering materials from disparate corners of his mind, Brainard’s writing style seems to mimic collage, the art form for which he would first gain recognition. The juxtaposition of these thoughts – morbid and mundane, lighthearted and weighty – isn’t played just for jarring contrasts and wry humour, even if the result is often disorienting, funny or both. It seems to transpose the often scattered nature of memory directly to the page, making for an intimate and visceral experience – raw autobiography without the cloudy filters of ego or pretence.

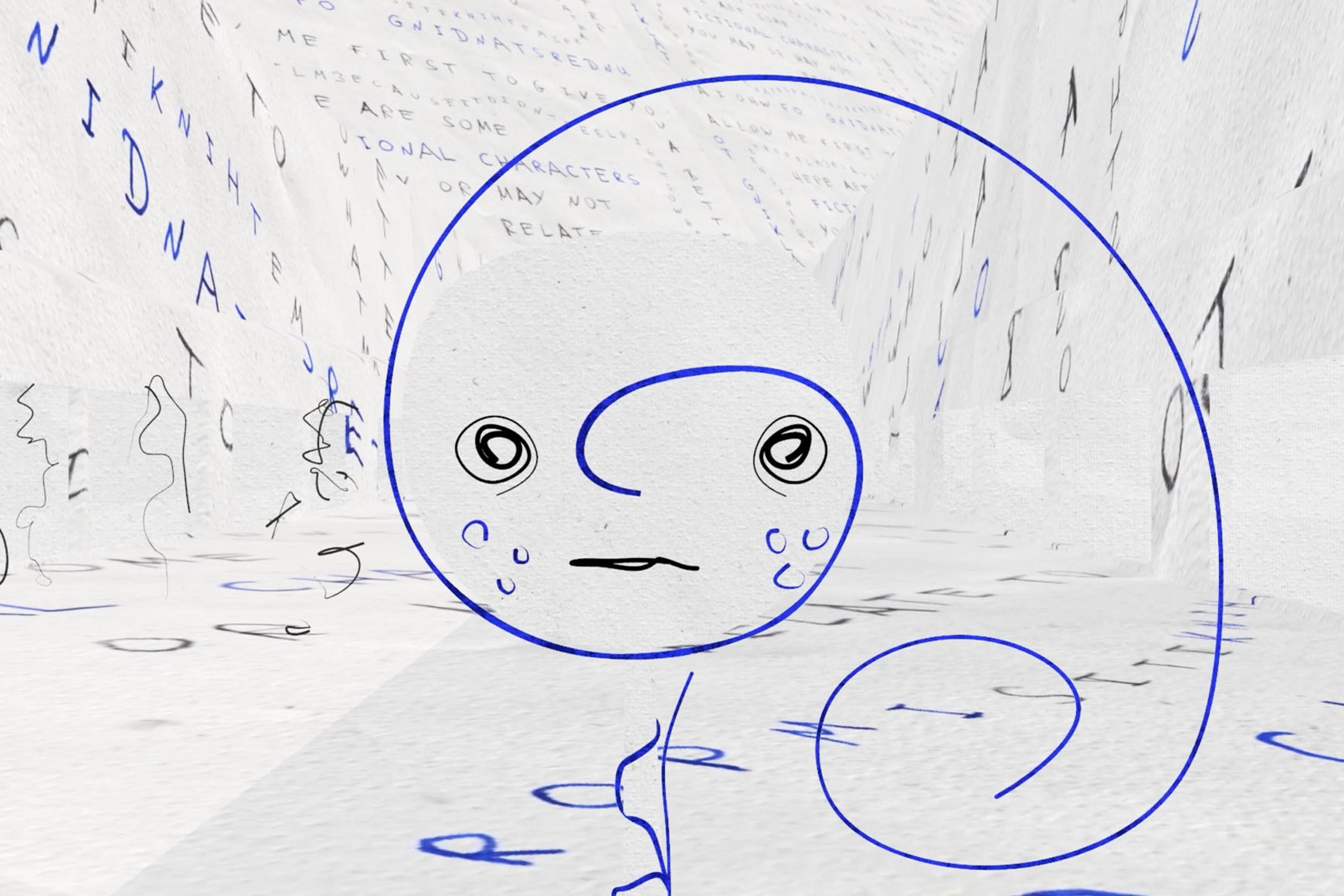

The US filmmakers Avi Zev Weider and David Chartier tug at these eclectic elements in this 1998 adaptation of Brainard’s work. Actors including John Cameron Mitchell, of Hedwig and the Angry Inch fame (2001), appear as bespectacled and cigarette-wielding Brainards at various life stages, populating memories that charm, entertain and even horrify. The accompanying music further draws out the emotional contrasts, shifting from bopping jazz bass to plaintive piano and strings. These brief vignettes, washing up and then washing away, form a delicate patchwork. It makes for a highly original and deeply intriguing deconstruction – not just of Brainard’s mind, but of the peculiar, emotional nature of memory itself.

Written by Adam D’Arpino