L’homme sans ombre (The Man with No Shadow) (2004) is a parable told in broad strokes. Hitting the beats of familiar morality tales, the animation follows an anonymous man moving through a stark, grey landscape who stumbles into a colourful, well-heeled world. He sells his shadow to a sinister character – donning bright red, of course – to stay among the untold riches, beautiful women and high society. Before long, he is shunned for his difference and left feeling hollow inside, whereupon he sets out on a journey to the Far East. There, his lack of shadow has a unique value and purpose, so he finally finds a home.

The film’s thin plot is unsurprising if you’re familiar with its director, the celebrated Swiss animator Georges Schwizgebel. In an interview with Animation World Network in 2011, Schwizgebel gave the order of aesthetic importance in his work as ‘the music, the movement, the visuals, and lastly the story.’ Here, the story is adapted from Adelbert von Chamisso’s novella Peter Schlemihl’s Miraculous Story (1814), with some of the source material’s details tweaked or left opaque. A sequence where the main character acquires boots that allow him to walk seven leagues per step, for instance, will likely be lost on anyone not already familiar with the work.

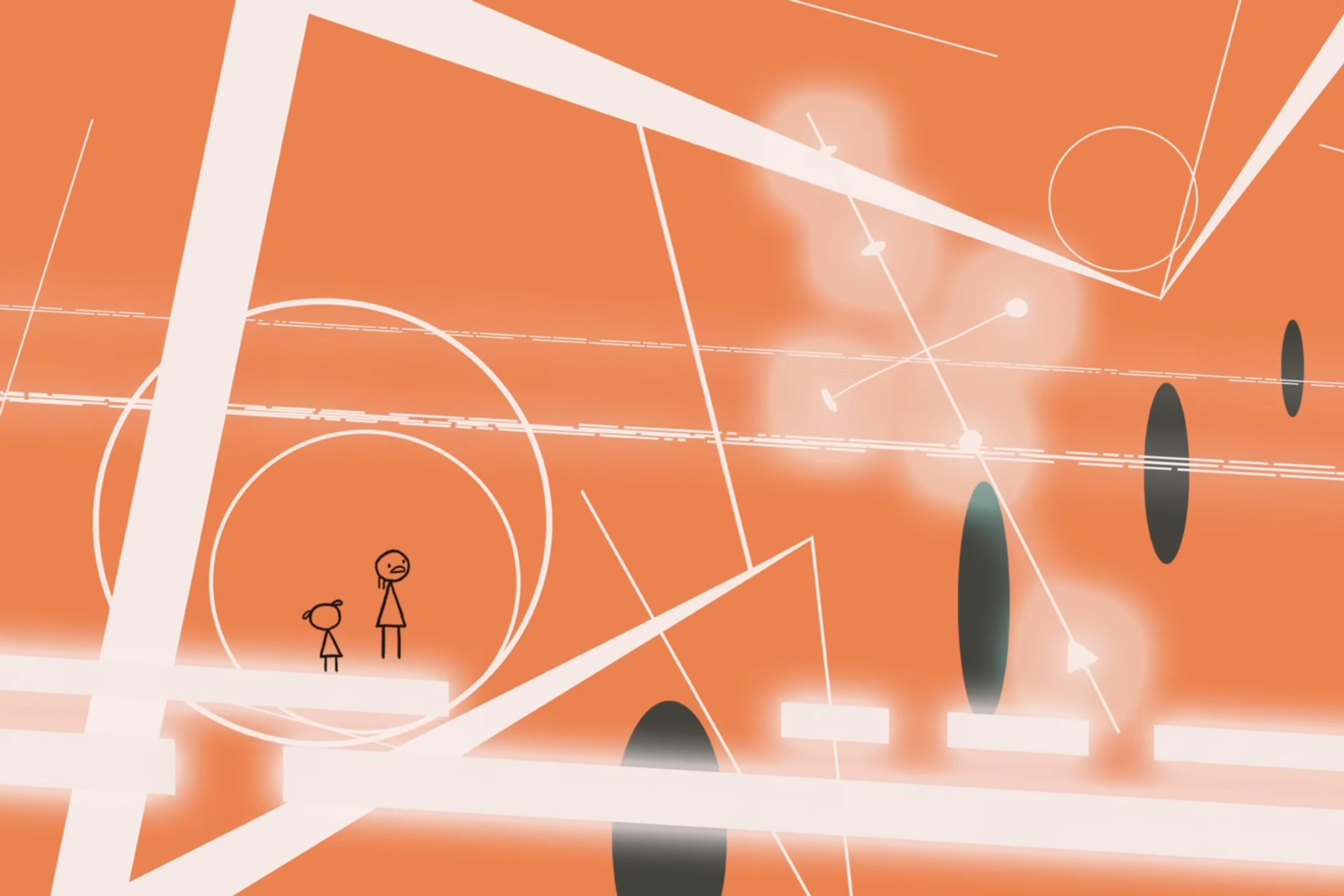

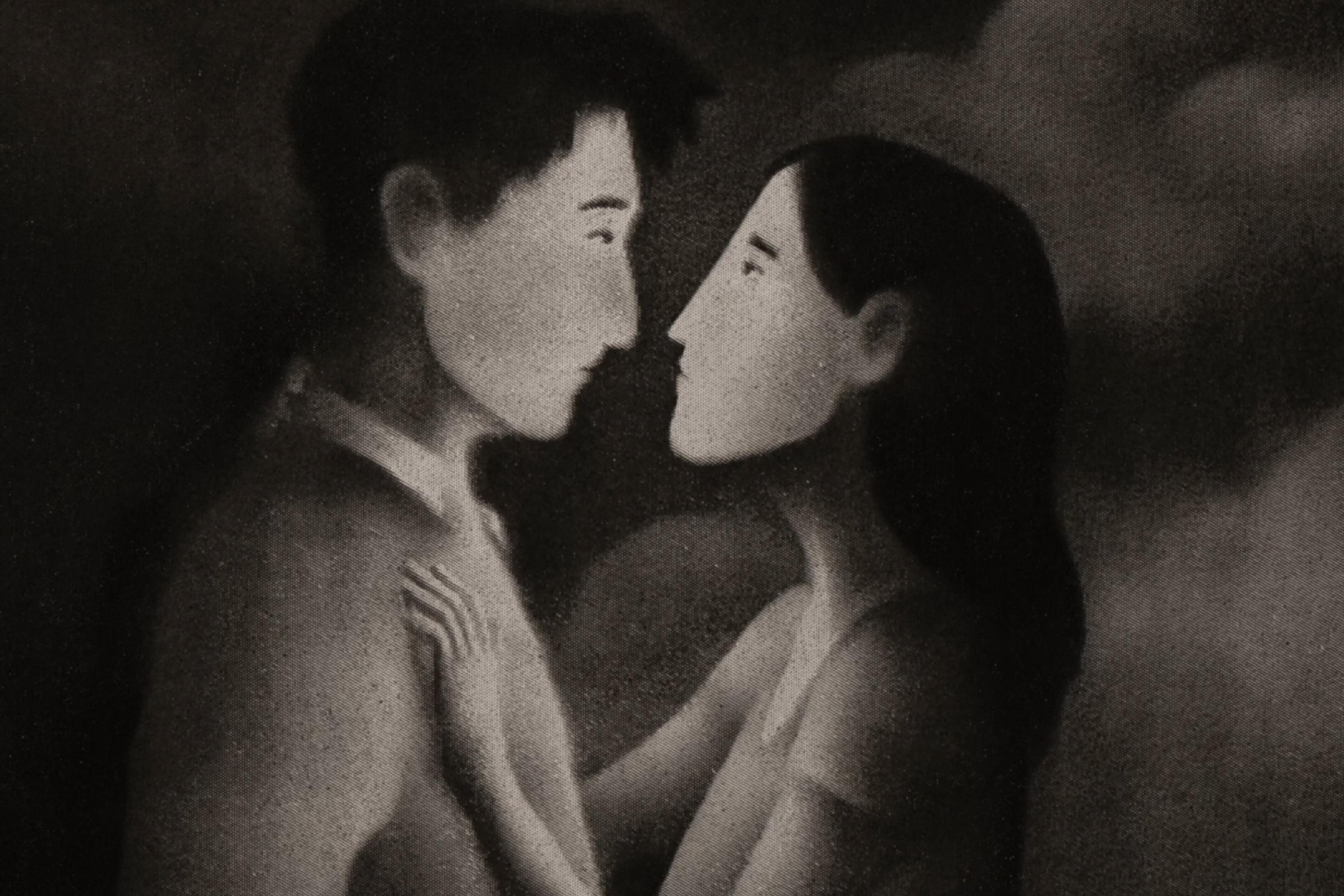

However, it’s the depth and detail of the artistry, rather than of the story, that make Schwizgebel’s short a classic, especially beloved in the world of animation. Here, the music – an aforementioned key ingredient in Schwizgebel’s work – is by the composer Judith Gruber-Stitzer. Tasked with creating half of the wordless experience with sound, Gruber-Stitzer crafts a lush score of strings, horns, piano, percussion and vocals to set the scenes and accentuate the emotional pull of the images. Providing the visuals in his celebrated paint-on-glass animation style – rendered by hand, frame by frame – Schwizgebel constructs a rich and meticulous world of shifting shapes that bleed into one another as the scenes seamlessly mutate.

Through his masterful grasp of light and colour, space and movement, Schwizgebel transforms a simple morality tale into a film that, while sparse in plot, finds richness in form. In the characters’ indistinct faces and the Escher-esque contortions of perspective, there is a deeper commentary on the moral complexity of navigating ambition and desire. And in the beautifully rendered conclusion – which diverges from that of its source – a powerful message about what it means to truly find your own place.

Written by Adam D’Arpino