If you had to explain walking to someone with no experience of it, what would you say? Everyday speech is full of references to walking, and its metaphors and aphorisms abound. From Aristotle onwards, philosophers have expressed strong views on how it should be done, and we’re often reminded of its health benefits. Nonetheless, as with anything so fundamental and commonplace, walking is difficult to approach with any freshness. Set out on that quest and you’re likely to step right into a puddle of clichés. This film offers something different – a beguiling response to a perhaps unanswerable question.

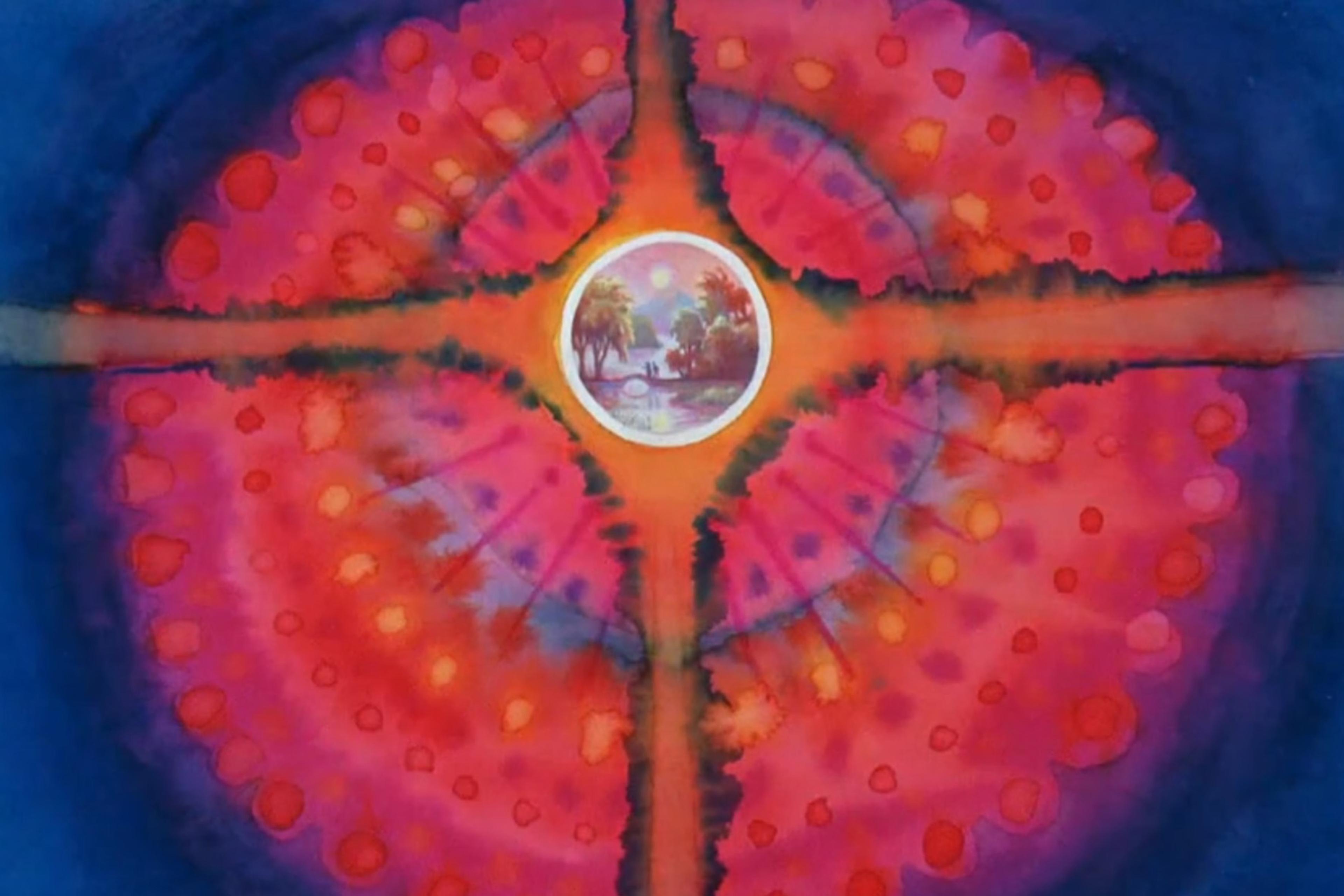

Walking by the Canadian animator and artist Ryan Larkin (1943-2007) made an indelible mark in the history of animation in 1968 with its innovative combination of drawing and colourwash techniques. The film was nominated for an Oscar® and seemed to augur a bright future for Larkin. However, he made only one more film – Street Musique (1972) – before a long run of drug addiction, alcoholism and destitution. A few years before his death, thanks in part to the success of Ryan, a strikingly original animation about Larkin, he returned to filmmaking, perhaps rediscovering the creative impulse that makes Walking such a subtle wonder.

Play is a crucial component of how we learn to walk, and though Larkin’s film isn’t about play per se, its origins are. Not only was he a close and curious observer of others, drawing on the capacity for mimicry that’s key to learning, but he’d also set up mirrors to play around with his own movements. Thus, his fascination with the body in motion becomes both a means of getting to know its movements and an act of creation.

Most descriptions of Walking focus on its distinctive observation of the many ways that people walk. But it’s not just the enjoyable parade of varied bodies in myriad movements that gives the film its swagger. An understated structure nudges us gently towards the hint of a narrative that enriches our path among the walkers.

The film starts with slightly melancholic music and a lone walking man who is the closest to a guide or protagonist we get in these five wordless minutes. As the music continues, the film segues to a sequence of largely static images of people. Some of them turn their heads, but none are in motion. The last of their lot, a boy on a balcony looking down, seems to notice the walking man from the beginning, who reappears seen from a new angle, as if we too are looking at him from above. Then an upbeat shift in the music ushers in a bevy of different types of walks and walkers, changing the mood from reflective to humorous. The final sequence begins with the solo walker as we first saw him, and with the same music. In this last stretch, more solo walkers pass by, then start to rush. A few do acrobatics and others dance. A small group runs, perhaps for sport or fun. And then larger groups move with purpose, suggesting people on city streets. Finally, the lone walker returns and the film concludes.

While a definitive interpretation of this iteration of images is elusive and unnecessary, the tonal and stylistic ebbs and flows have an effect on our viewing. The first sequence suggests something of what it’s like to walk around and see people – occasionally to be noticed. The second sequence plays like a reverie in which caricature-like proportions and physical features draw attention to walking itself through exaggeration. The third sequence merges the music of the first with the momentum of the second as the act of walking becomes still more varied, exploring movement for its own sake as as well as the utilitarian purpose of getting somewhere. Each time we return to the lone walking man, the connective thread, we experience his trajectory in relation to everything else with tantalising but ephemeral possibilities.

Maybe this was his walk and what he witnessed. Maybe it was his daydream as he walked. Maybe it’s something else altogether. In offering these wisps of a story, Larkin gives us a path to walk too, one in which our imagination can wander as it pleases.

Written by Kellen Quinn