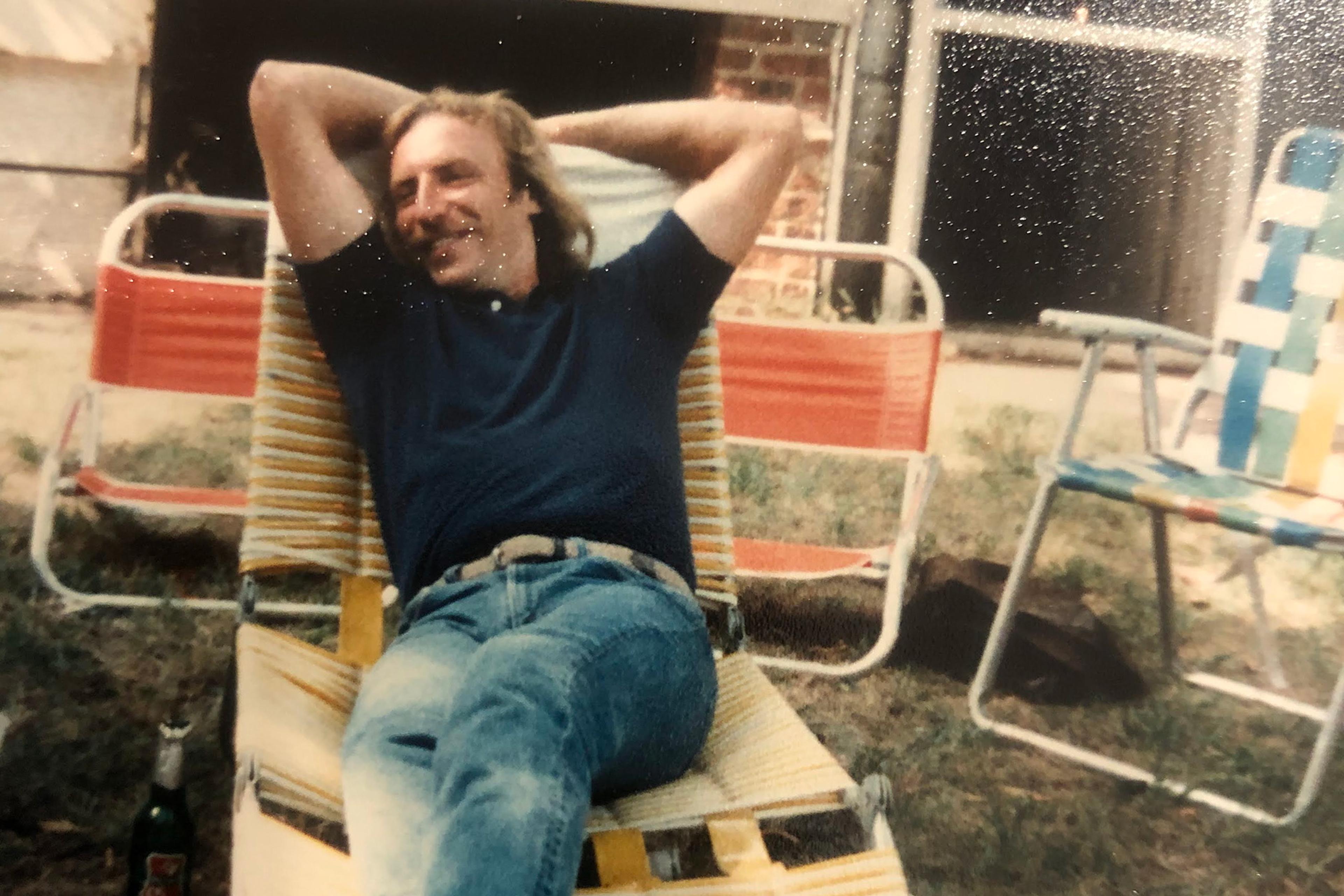

My mom died of cancer in November 2020 and, as clichéd as it may sound, not a day goes by that I do not think of her and miss her. Her death sparked in me a need to discuss death and grief. It is in talking about it, contemplating it, facing it, and inviting others to join me in these discussions, that I have been able to construct ways forward.

While the specifics of my loss are mine, I know I am not alone in knowing grief. Perhaps many of you reading this also know its heaviness. As a medievalist and literary scholar, it is unsurprising that I find comfort in stories and the written word. One text that particularly resonates with my reaction to grief is the Andalusi polymath Ibn Tufayl’s 12th-century philosophical tale, Hayy Ibn Yaqzān (‘Alive Son of Awake’). Among other details, it is an autodidactic story where the protagonist contemplates his place within the universe. This self-guided journey is prompted by the death of the only mother he’s ever known, a gazelle who raised him from infancy. It is this life-changing loss that prompts Hayy to explore the divide between the body and the soul – or the material and the nonmaterial. He meditates on how the soul must be part of a larger creational energy uniting everything in nature, ultimately discovering ‘God’ without any revelatory text.

In Hayy I saw aspects of myself: someone whose mother-loss prompted them to question existence and seek a way to support the weight. This story doesn’t ‘solve’ grief, nor should we want anything to do so, but it does prompt questions and reflections that can help us lean into the discomfort. What can we do when we are forced to face death? Do we continue ignoring it or do we weave it into our understanding, possibly creating a more nuanced appreciation for both the fleetingness of life and its interconnected nature? I find that it is this very activity that can arm us with the tools needed to continue living in a world that no longer physically holds our loved ones as we once knew them.

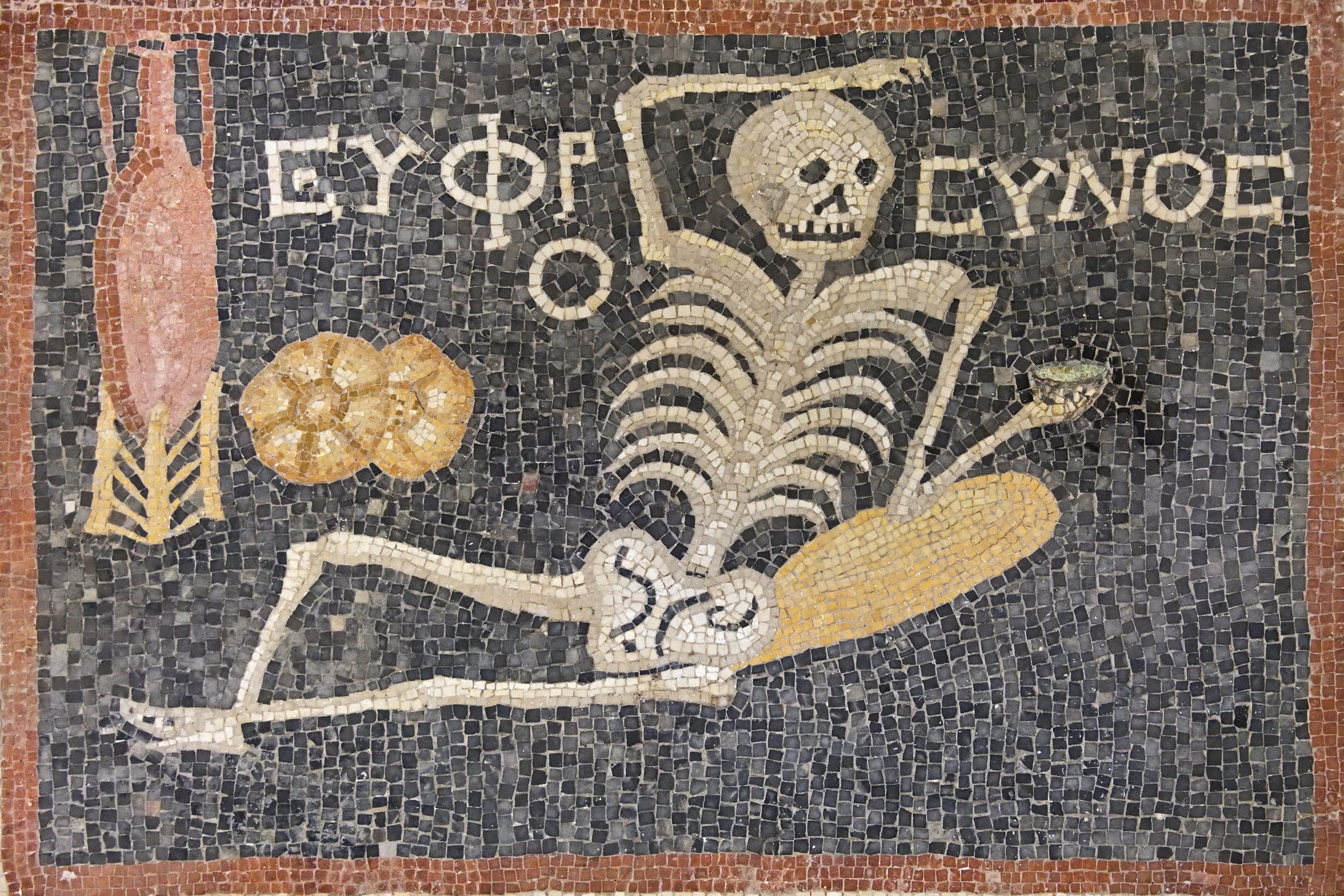

Ibn Tufayl’s Hayy Ibn Yaqzān circulated widely in North Africa and Iberia in its original Arabic until the 14th century when it was translated into Hebrew. By the 17th century, it was translated into Latin and English, and it has many modern editions today. Regardless of the language, the core message is that of how, through introspection, without the intervention of social norms or religion, one can reach a mystical understanding of the cosmos. As a work, it is widely philosophical but especially powerful considering the protagonist’s connection with grief and love. Indeed, Hayy’s desire to understand his role in the cosmos is triggered by the death of his gazelle-mother. She raised him, and years later, upon seeing her lifeless body, he tries to fix her. He searches her body for a blockage yet sees no physical damage. He concludes that something is missing and that she ‘who had nursed him and showed him so much kindness could only be that being which had departed’ and that her body was ‘simply a tool of this being’. Her form changed.

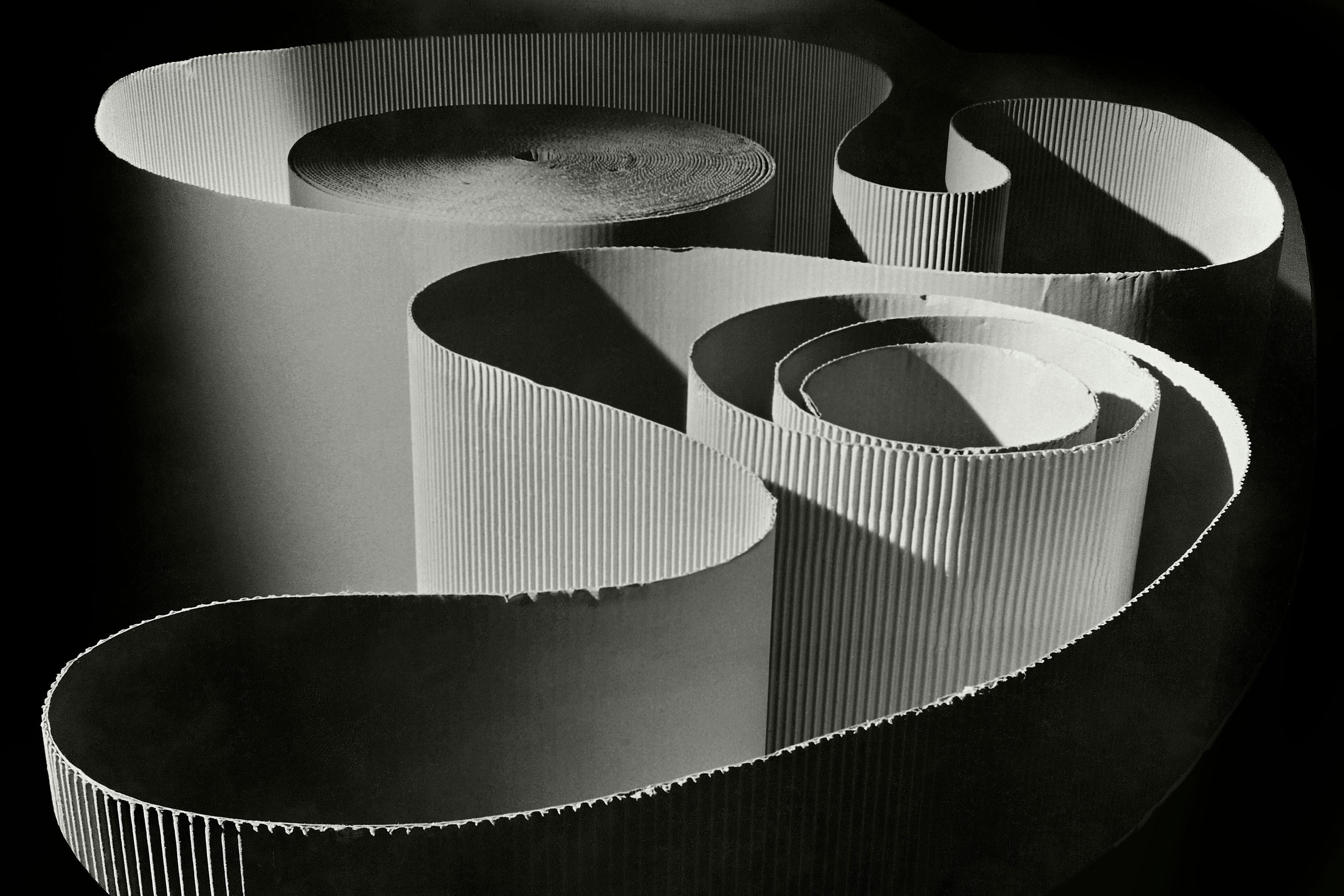

Her death opened his mind to conceiving existence beyond the material world and drove him to see the cyclical nature of energy in the ever-transforming world. In apprehending these patterns, Hayy came to the realisation that ‘all physical things, despite the involvement of diversity in some respects, are one in reality’. If everything is one, then nothing is lost, it is simply changed. When applied to the death, this meant that those that died ‘have taken off one form and put on another’. This means that his mother, and by extension anyone, never truly dies in the sense of ceasing to exist, but rather takes on a new form, free from the constraints of any one material entity.

For me, this type of conclusion was so very comforting. My loss stems from the shed material appearance of the energy that fuelled my mom. I will always long for the form she once held, that way of being, but seeing the nonmaterial as part of the larger cosmic energy calms much of my anxiety. It’s not that she, as she was, is now floating about, but rather that the energy that made her remains, even with the loss of her material form.

While written in an Islamic context, a lot of what Hayy realises through observation and contemplation mirrors many mystical, neo-Platonic, Sufi and hermetic ways of thinking. These different approaches share a common theme of unity. Indeed, Hayy is able to reach some of the same conclusions without any official doctrine. It is this universality that most captured my attention. One of his conclusions is that everything is cosmically connected through energy, and that this unity is powered by love – something reinforced in the introductory pages of the story. Indeed, many magical treatises of the time echo the power of love. This cyclical thesis can form part of more institutionalised modes of knowledge but is also inherently accessible to us without direct instruction through observation, as Hayy demonstrates. Within this line of thinking, the good news is that love, as something nonmaterial, remains. Moreover, the energy that fuelled loved ones lingers as a part of the cosmos, just manifested differently. Everything is knit together. While the materiality of existence creates difference and individuality, there is a comfort in seeing the interconnection of all things.

We don’t have to become wild mystics like Hayy and seclude ourselves to benefit from recognising the added layer of unity within difference. In many modern societies, death, grief and loss are rarely discussed openly. In such situations, a disposition to consider the ways nothing is really destroyed, but is rather transformed yet also interconnected, can be very rare to encounter – in fact, something many never encounter – but it can also bring immense metaphysical comfort.

The cyclical nature of life and death helps me to see beyond my self

Practically, what this framework does for me regarding my mom’s death is that it allows me to move forward with her in shifting how I understood what ‘her’ was. Now I am deviating slightly with a more secular approach to Hayy’s discoveries and Ibn Tufayl’s commentary on the ways of knowing ‘God’ or the universe, but I think that it is such contemplations and other pantheistic/panentheistic non-dual mentalities that are essential for embracing grief in a world that too often stifles such discussions as taboo. Just as in the case with Hayy, deep loss can trigger existential questions that have the potential to progressively drive forward conversations of death and grief, despite their relegation to the margins.

As long as I identify with my individual material self, I will always long for mi mami’s physical presence as I knew it. The cyclical nature of life and death, of the transformation of nonmaterial energies that give life to the material, helps me to see beyond my self, a picture of the cosmos really, that helps me slowly let go of the fear of death. It’s still very much an endeavour in progress. Even a fleeting awareness of the temporality of it all helps me continue to see her in beautiful scenes of nature like sunrises, the Sun’s rays reflecting fall leaves as birds fly by, or the various stages of the Moon in the night sky. There is energy all around us and energy within us. Whether or not we’ve met grief yet, beginning to have these conversations can help us map a path we will all inevitably walk.