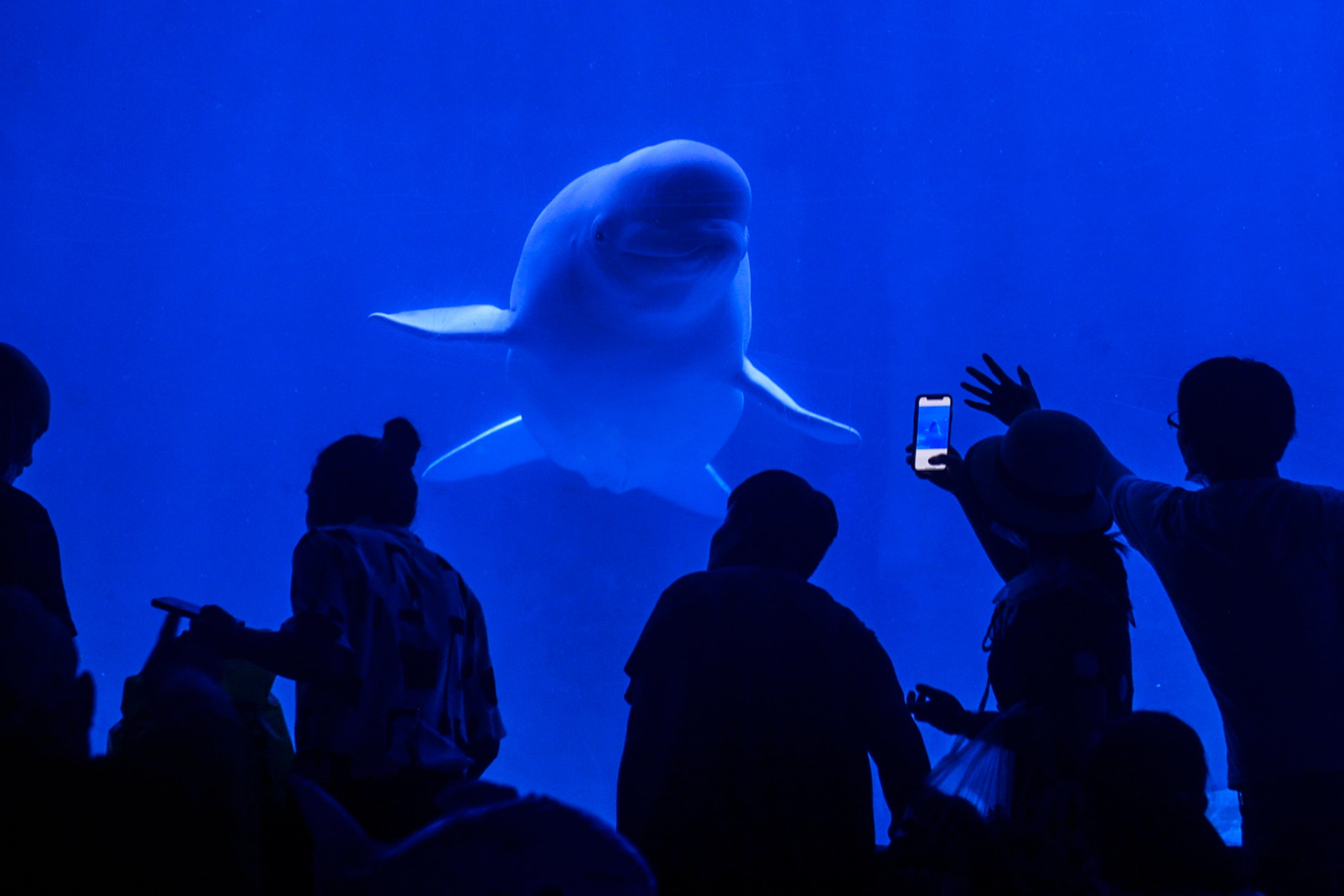

Breathes there a child with soul so dead who never to herself has said ‘I want a dog … a cat … a horse … a turtle … or a baby hippopotamus’? Maybe so, but such a youngster would be very unusual. The human-animal connection is as old as our own evolutionary history, which is not surprising given that we, too, are animals. Even if denied a pet, nearly every child (at least in the Western world) grows up drenched in animalia, from pyjamas to cartoons, toys, songs, blankets, underwear, socks and even wallpaper. Moreover, it is difficult to imagine children’s books and stories that are not inhabited – make that, dominated – by our animal relatives. This makes it difficult, indeed impossible, to determine the extent to which this zoophilia derives from persistent exposure, itself driven by adults, who typically assume that this is what children want.

The likelihood, however, is that such engagement – a specific manifestation of what the late biologist Edward O Wilson called ‘biophilia’ – is to a large extent innate, given that it appears to be crosscultural, and substantially manifested by adults themselves (who, admittedly, had been similarly exposed to animals and animal-related material when they were young). The internet is awash with cat and dog videos, along with many other animals.

All of the above makes it somewhat surprising, perhaps, that Western religions in the Abrahamic tradition have long been concerned to separate us from animals, an effort that began as early as Genesis 1, wherein it is proclaimed that God created humankind to ‘rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground,’ which not only seeks to distinguish the ruled from the rulers, but has also given theological legitimacy to much cruelty. There are, fortunately, other perspectives. The writer-naturalist Henry Beston spent many months alone in a small cabin on the Cape Cod peninsula, writing his masterpiece, The Outermost House, in 1928. But he wasn’t really alone, being accompanied by a plethora of wildlife. While also acknowledging a degree of separation from the animals around him, in one of the finest passages ever written about animals, Beston urged that, rather than lording over other life forms, we recognise and treasure their uniqueness. ‘They are not brethren,’ he wrote, ‘they are not underlings: they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.’

Human beings began domesticating animals about 20,000 years ago, probably beginning with dogs, and we have co-evolved ever since, not just with them, but as them. Moreover, we still are them.

The American Pet Products Association conducted a National Pet Owners Survey in 2017-18, according to which more than two-thirds of US households – 84.6 million families – have at least one pet, mostly dogs and cats, although this tabulation includes horses, birds, reptiles and fish. According to a 2011 report in The New York Times, 23 per cent of pet owners cook special meals for their pets, 65 per cent buy them Christmas gifts, and 70 per cent say they sometimes sleep with their pets. (Not included, one presumes, are horses, fish and reptiles.) Nearly all say that they consider their animals part of their family, and fully 40 per cent of married women maintain that their pets give them more emotional support than do their spouses. Research has revealed many empirical, medical benefits derived from pet ownership, as would be expected insofar as association with animals constitutes a key part of the environment in which people evolved. Thus, pets have been found to raise circulating oxytocin and lower blood pressure. There is growing recognition that animals, particularly dogs, can contribute to recovery from PTSD. Moreover, people who live with dogs are 15 per cent less likely to die of heart disease, consistent with the hypothesis that being animal-involved reduces stress.

Not all people are equally animal-involved, and I acknowledge occupying one extreme, having spent my professional life studying a variety of species, each in its natural environment. At home, I am surrounded by multiple dogs, cats, horses, goats, chickens, a three-legged box turtle, a snuggly ball python and an insouciant, brilliant, often irascible and always demanding cockatoo. Especially in these pandemic days, they provide companionship, comfort, amusement, occasional anxiety (when they are injured or fall ill), a reliable – and sometimes resented – structure to our days, and an unending drain on our finances. Most city-dwellers, admittedly, don’t have these experiences but, given the difficulty of keeping even a few animals in an urban environment, it is notable how many urbanites do so.

We have a tractor. Our horses don’t pull a plough. When we ride them, it’s for exercise and the pleasure of connecting with them, rather than to get from one place to another. For more than 99 per cent of human history, however, our equine compatriots were not just companions, but crucial for transportation. Consider the current proliferation of cars, trucks, buses, airplanes, railroads – and then imagine replacing all of them with literal horsepower. One of the arguments made by early automobile manufacturers in favour of their product was that it would clean up the mountains of smelly, unsightly and unsanitary horse poop that clogged city streets. Now we’re clogged by internal combustion engines, gagging on carbon monoxide, and overheating because of fossil fuels.

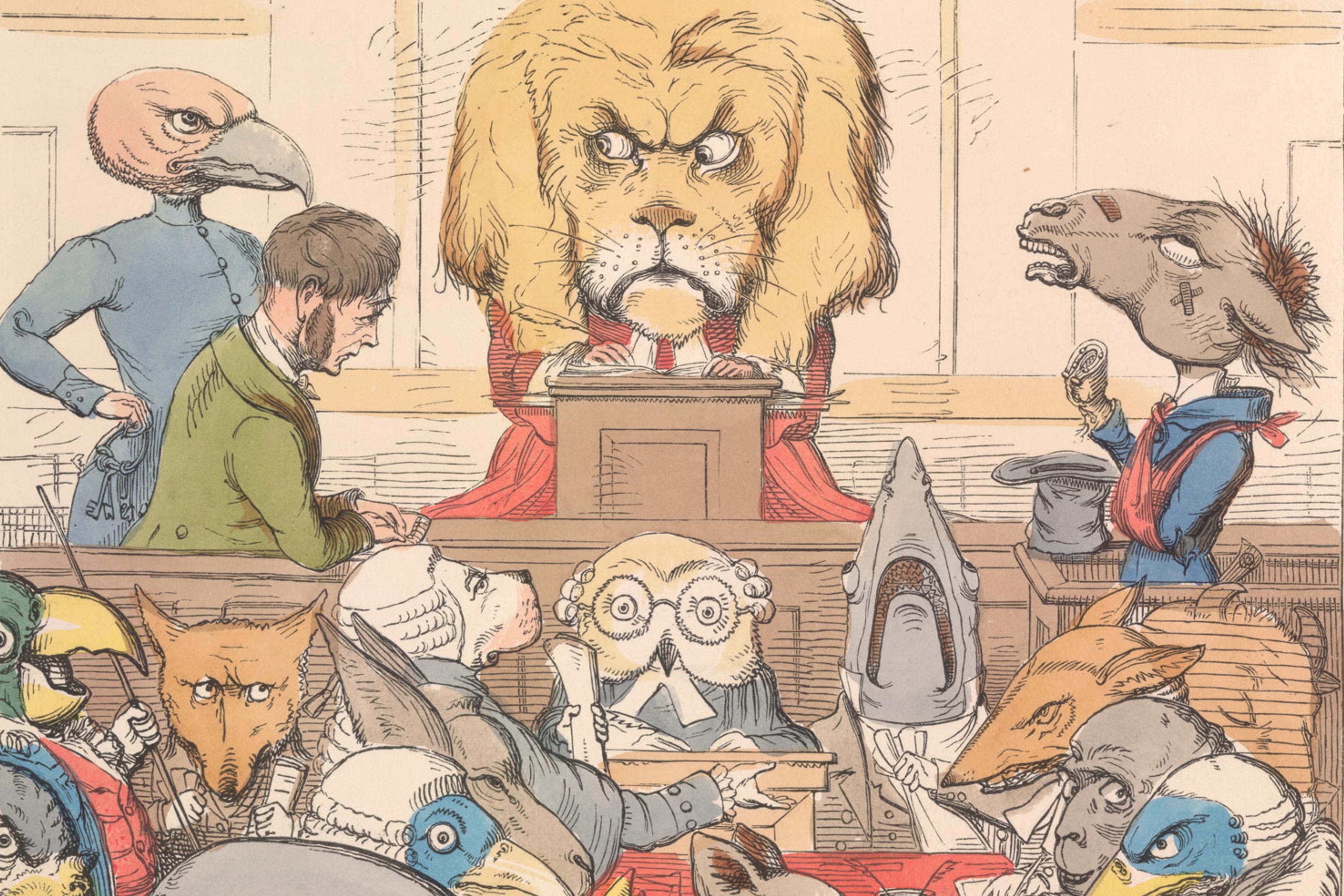

Fellow prisoners typically have a complex and intimate relationship, a reality not limited to ‘primitive’ peoples, who necessarily live close to the natural world and its denizens. In the sweep of human experience, mutuality was unavoidable. Even in modern times, every known human society is enmeshed in nonhuman animals, as companions, guardians, mythic personages, fellow travellers and even advisers, although not all of these connections have been collegial: our ancestors didn’t merely befriend animals. They ate them, appropriated their eggs, drank their milk, wore their skins, made weapons and other implements from their bones, tortured them, rode them, used them as labourers and warriors, and ritually slaughtered them. Also worshipped and feared them, all the while – at least sometimes – deriving pleasure and inspiration from them. Spectacular artwork in the Lascaux caves in southwestern France depicts great cats, a bird, a rhinoceros, four enormous black bulls – aurochs, now extinct – and (oh yes) even the occasional Homo sapiens – testimony to the imprint other animals have had on our consciousness. Friend or foe? Doubtless both.

With any closely interwoven association comes a downside. The Taung Child, the first fossil hominin, discovered in 1924 in South Africa, was a three-year-old Australopithecine whose skull shows puncture marks just below the eye sockets that resemble those made by the talons and beak of modern-day eagles when they prey upon monkeys. When our ancient ancestors weren’t victimised by disease, starvation, malnutrition, adverse weather or each other, they were almost certainly preyed upon by larger, faster, stronger, fiercer and more lethally equipped predators – which is to say, other animals such as sabre-toothed cats, dire wolves that must have been dire indeed, lions, gigantic cave bears (far larger than today’s grizzlies), all of which must have loomed large in our predecessors’ days as well as their nightmares.

Even now, in the 21st century, there are ‘maneaters’ out there, including lions, tigers, hyenas, crocodiles, sharks, pythons, anacondas and bears. And don’t forget those other profoundly lethal animals who don’t prey upon us but who – nearly always because of our blundering rather than their malevolence – used to kill us, and still do: notably, venomous snakes. This is not counting those creatures, such as mosquitoes, tsetse flies and rats, that as vectors for lethal pathogens are indirectly responsible for many millions of human deaths.

It shouldn’t be surprising, therefore, that what E O Wilson aptly identified as biophilia – a love of and need for the biological world – has its own negative counterpart, especially toward our fellow animals. Call it ‘zoophobia’. It can be occasioned by seeing certain kinds of animals, not only those that might kill us but those that make us uncomfortable because they threaten to cause us pain, such as spiders or centipedes. Zoophobia even includes, for some people, a less explicit but no less genuine fear, not of being killed or hurt by animals, but of being them.

For some of us, the mere existence of our nonhuman brethren can be disturbing. ‘In an aversion to animals,’ wrote the philosopher Walter Benjamin in 1928, ‘the predominant feeling is fear of being recognised by them through contact. The horror that stirs deep in man is an obscure awareness that something living within him is so akin to the animal that it might be recognised.’ Nonhuman animals can thus provide a flexibly distorted image of ourselves, as in a fun-house mirror, allowing us to criticise, laugh, exploit or recoil. Thus, propaganda for war and genocide has long employed zoophobia to literally dehumanise opponents by labelling them rats, reptiles, insects and other ‘vermin’. Alas, the current pandemic has raised in the minds of some people the spectre that certain animals, and by hyperbolic extension, animals generally, are virus-laden villains, whether bats, pangolins or other species that are reservoirs for pathogens that occasionally spill over to literally plague us. But such events nearly always result not from their malfeasance, but from ours, notably our disruption of their (and by extension, our) ecosystems.

Whether or not they want a pet, love them, fear them or ignore them, and regardless of how urbanised or self-consciously civilised such persons may be – or however much some might disdain their fellow creatures, even to the point of refusing to acknowledge kinship and connectedness – no one is, or likely ever will be untouched by animals. So, let’s give the last word to Mowgli, from The Jungle Book (1894) by Rudyard Kipling: ‘We be of one blood, ye and I.’