Your body is the most intimate part of your self – a ubiquitous presence in your life. To know something ‘like the back of your hand’ is to have a profound, even infallible understanding of it. Perhaps you think you have a perfect familiarity with your own body. Yet misperceptions and mental distortions of the body are at the centre of many remarkable clinical problems, and they even appear to some degree in healthy individuals. These phenomena provide a fascinating contrast to the seeming immediacy and directness of the everyday experience of the body.

In neurology, for example, patients who have had limbs amputated commonly experience vivid phantom sensations of their missing arm or leg. Other patients report their arm performing actions outside of their control – a condition memorably portrayed, in exaggerated fashion, by Peter Sellers in the film Dr. Strangelove (1964). Some patients with brain damage following strokes deny obvious impairments, such as being unable to move their hand, or they might even deny that the hand is their own. Similarly dramatic conditions have been described in psychiatry. People with body dysmorphic disorder become fixated on the belief that some part of their body is hideously ugly. Other patients feel that one of their limbs – an arm or, more commonly, a leg – somehow doesn’t belong, and many express the desire to have it surgically removed.

The most well-known misperceptions of the body are probably those seen in eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa. Even patients who are emaciated will often continue to insist that they weigh too much. The mental distortions of body size among people with eating disorders can be measured using perceptual tasks. For example, in the widely used ‘moving caliper’ method, the participant adjusts the distance between two lights to match the perceived width of some part of the body, such as the hips, waist or shoulders. The judged width of each part can then be compared with the actual width. A consistent finding is that patients with anorexia and bulimia tend to overestimate the width of their bodies more than do participants without these conditions, a pattern confirmed by a recent meta-analysis of this literature.

Looking at these various conditions, it might seem as if distortions in body perception are inherently a sign of illness. But the evidence of such distortions extends well beyond those who meet the criteria for a neurological or psychiatric disorder. In fact, distorted representations of the body appear to be a basic feature of mental life, as I argued in a recent paper.

One illustration comes from a study I conducted with my colleague Patrick Haggard at University College London. We covered participants’ hands with a board and asked them to use a long baton to indicate the perceived location of the knuckle and tip of each finger. Based on their judgments, we constructed perceptual maps of hand size and shape, which we then compared with actual hand structure. These maps were massively distorted, showing overestimation of hand width and underestimation of finger length. Similarly distorted maps are found even when people simply imagine that their hand is under the board (while resting the hand in their lap), indicating that this phenomenon arises from the mental image people have of their hand. Such effects are not specific to the hand: overestimation of body width has also been found in perceptual maps of the face and legs.

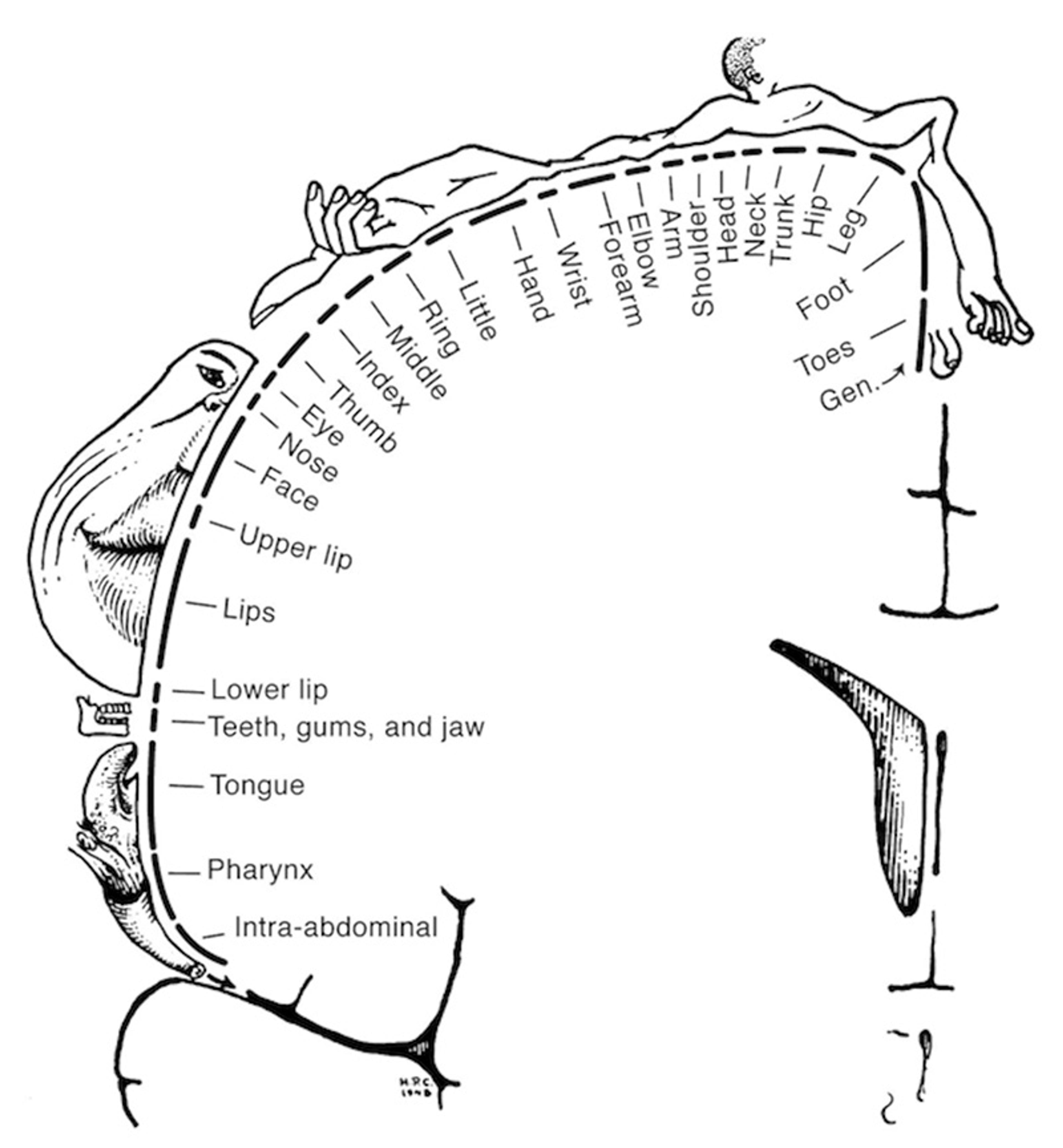

We can find another example of typical body misperception in a curious illusion first described by the 19th-century German physiologist Ernst Weber. He found that, as he moved the two points of a compass across his skin, it felt as if the distance between the points changed. Specifically, the distance between the touches felt bigger on more sensitive regions of the skin (such as the palm of the hand) than on less sensitive regions (such as the forearm). Subsequent research has replicated this result and shown a systematic relation between the sensitivity of body parts and the perceived distance between touches. Weber’s illusion provides a perceptual echo of how the brain’s body maps – the areas of the cerebral cortex that correspond to different parts of the body – are proportionate to the sensitivity (not the size) of those body parts, as illustrated by the well-known cortical ‘homunculus’.

Wilder Penfield’s map of the sensory homunculus. Cortical representations for various body parts as mapped onto the parietal cortex of the human brain. Adapted from Penfield and Rasmussen’s The cerebral cortex of man (1950). Source: http://cercor.oxfordjournals.org/content/23/5/1005.ful

Similar illusions are evident when comparing the perceived distances between touches oriented in different ways. The distance between two touches on a person’s hand is perceived as about 40 per cent larger when the touches are oriented across the width of the hand rather than along its length. Comparable biases have been found in the perception of the feet and face. As with the perceptual maps we’ve studied, in these examples people seem to be experiencing their body as squatter and fatter than it really is.

In a recent neuroimaging study from my lab, led by my colleague Luigi Tamè at the University of Kent, we found evidence of similar distorted neural representations of the hand in the primary somatosensory cortex – the very first place in the cerebral cortex where tactile signals are processed. Perceptual distortions in touch, it seems, are linked to the basic organisation of body maps in the brain.

The tendency to overestimate the body’s width shows up in a variety of tasks – and it appears, to different degrees, in those with and without the conditions commonly associated with body distortions. It is apparent in classic studies that compared anorexia or bulimia patients with groups of healthy control participants. For example, in one study using the ‘moving caliper’ method, patients with anorexia overestimated their waist width by 42 per cent, on average. Similar results have been found for several regions of the body, the most commonly measured being the waist, hips, shoulders and face. However, research shows that the comparison groups tend to overestimate their own body width, too. In that same ‘moving caliper’ study, the healthy participants overestimated the width of their waists by nearly 17 per cent – less than the patients, but still a substantial misperception of body size.

Other studies that have tested large samples of healthy people have found similar distortions, in both men and women. One study of 100 healthy UK adults, for example, found that the size of the chest was overestimated on average by 23 per cent, the waist by 24 per cent, and the hips by 13 per cent. Notably, however, no overestimation was found when participants used the same apparatus to judge the size of a box, showing that the distortions are specific to the body.

Thus, the distortions of body image seen in eating disorders do not reflect the emergence of a new feature of body perception, but rather an exaggeration of a bias that appears to be a widespread – if not universal – feature of how people perceive their bodies. It is not well understood what factors might lead these distortions to become exaggerated, although cultural factors related to the depiction of idealised bodies in mass media are likely involved. Indeed, the introduction of Western television into non-Western societies has been linked to increases in disordered eating and body image concerns.

In some instances, perceptual body distortions might relate to psychological wellbeing even in non-clinical samples. For example, a recent study led by my colleague Lara Maister of Bangor University used a technique called ‘reverse correlation’ to reconstruct participants’ mental representations of their body and face shape. By adding different visual noise to two images of a face and asking people to judge which one looked more like them – and then repeating this process many times – the research team allowed the participants to form implicit ‘self-portraits’. We found that the amount by which people’s facial self-portraits differed from the actual shape of their faces was related to lower ratings on a measure of social self-esteem.

Body distortions, then, might be both a basic feature of mental life and, at increased levels, a risk factor for mental health issues. While the misperceptions seen in patients might seem totally distinct from most people’s typical experience of their bodies, research suggests that these distortions have close links to basic processes operating in all of us. This is also true of other aspects of mental life, such as fear – an experience that is nearly universal, but that results in maladaptive phobias in some people. In a similar way, people who do not experience clinically significant levels of body misperception might have more in common than they imagine with people who do.