When the American poet Emily Dickinson began an ongoing conversation with herself about her own inner world, she discovered one of the most unique sources of creative inspiration in the history of poetry. It was inexhaustible and, like the breath of the Buddhist, it resided within her, accessible wherever she was: when she wrote, she withdrew from the world, entering an interior space that, before long, became her poetic subject. As she gradually withdrew from the social world, Dickinson became a remarkable transcriber and translator of inner experience – what in 1855 she called ‘a solitude of space’ (in lyric number 1,696) – and her interior tracings often yielded extraordinary poems.

Most of us would feel deeply distressed by the thought of being the only ones in our heads, sequestered from others and from daily living. Such isolation can be painful and disorienting, not least because it demands a naked encounter with oneself, and with no escape into something concrete or into any engagement with another. When protracted, such experiences can be terrifying: it’s why monastic seclusion is not for the fainthearted; why, in prison life, solitary confinement is among the harshest of punishments.

Yet the way Dickinson inhabits quiet isolation in her poems is fully comfortable. For her, ‘The Brain – is wider than the sky’ and ‘deeper than the sea,’ as she wrote in 1863. There is always something in the mind to follow, to chart or explore. Perhaps we can learn from the way Dickinson uses self-isolation to generate – rather than drain off – creative energy. Speaking in an inward voice, she professed to be afraid to ‘own a Body’ or ‘own a Soul’, but she nonetheless squared up to owning both, setting out to investigate and understand what she had been given. ‘I felt my life with both my hands / To see if it was there –’, she writes in 1862, with the kind of stark presentness that was a distinguishing feature of her verse. In Dickinson’s hands, poetry was a medium of vivid and energetic self-encounter.

Dickinson was born on 10 December 1830 into a prominent family in Amherst, Massachusetts. Her father, Edward Dickinson, served as state representative, and her grandfather, Samuel Fowler Dickinson, was a founder of Amherst College; Emily visited her father briefly in Washington, DC in the House of Representatives as a young girl. That said, throughout her life, travel of any kind was rare. She attended Amherst Academy and then boarded for a year at the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (1847), after which she returned to her family’s home in Amherst, a house called the Homestead, where her closest companions – her sister Lavinia and brother Austin – also resided.

Through the 1850s, Dickinson gradually settled into a solitary existence, rarely leaving the Homestead and its parameters, and deliberately sequestered from others: ‘I do not cross my Father’s ground to any House or town,’ she announced in a letter in 1869. We know that she took enormous pleasure in reclusive activities around the property: gardening, cooking, reading, writing, and sewing booklets of verse. In her later years, she retreated increasingly to her room. This full withdrawal into the space of the home, unexpectedly, opened possibilities, for she thrived, and began to develop her distinctive poetic style.

Although some of her biographers, among them John Cody and Albert Gelpi, see a lack at the centre of her existence, Dickinson’s profound isolation granted her perspectives – ranging from the mystical to the ruminative to the critical – that daily social living might have cut off. Isolation proved a guard against rigid social expectations, especially those imposed on women, which would likely have restrained her poetic craft. Alone with herself, and her boundless creative explorations, she found a world in inner space. Not for her were marriage, motherhood or domestic cares: ‘I’m “wife” – I’ve finished that’ she writes with cutting scare quotes in 1861. For Dickinson, sequester was a feminist act of independence. And, with that understood, she was able to share a lively written correspondence with friends and editors.

Dickinson’s compressed, compact and, often, emotionally brutal poetic style arises from a sense of what the critic Robert Weisbuch in 1975 wonderfully called ‘scenelessness’ – that is, her standing apart from things, persons, places and times, and inhabiting instead an intensely inward world. The ‘scene’ is literally missing in her poetry, and in its place stands the poet’s receptiveness, a state that gives people, places and things their significance: ‘The Outer – from the Inner / Derives it’s [sic] magnitude –’, as Dickinson put it in 1862. Released from the push and pull of daily living, Dickinson sees things anew and from a boundary-breaking perspective. Her signature dashes mirror the starts and stops of the human mind, while many of her poems read as puzzling and luminous transcripts of thoughts, feelings, sensations, perceptions and ideas that are suspended, standing unanchored and unattached. In a letter in 1869 to her editor Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Dickinson wrote: ‘there seems a spectral power in thought that walks alone’.

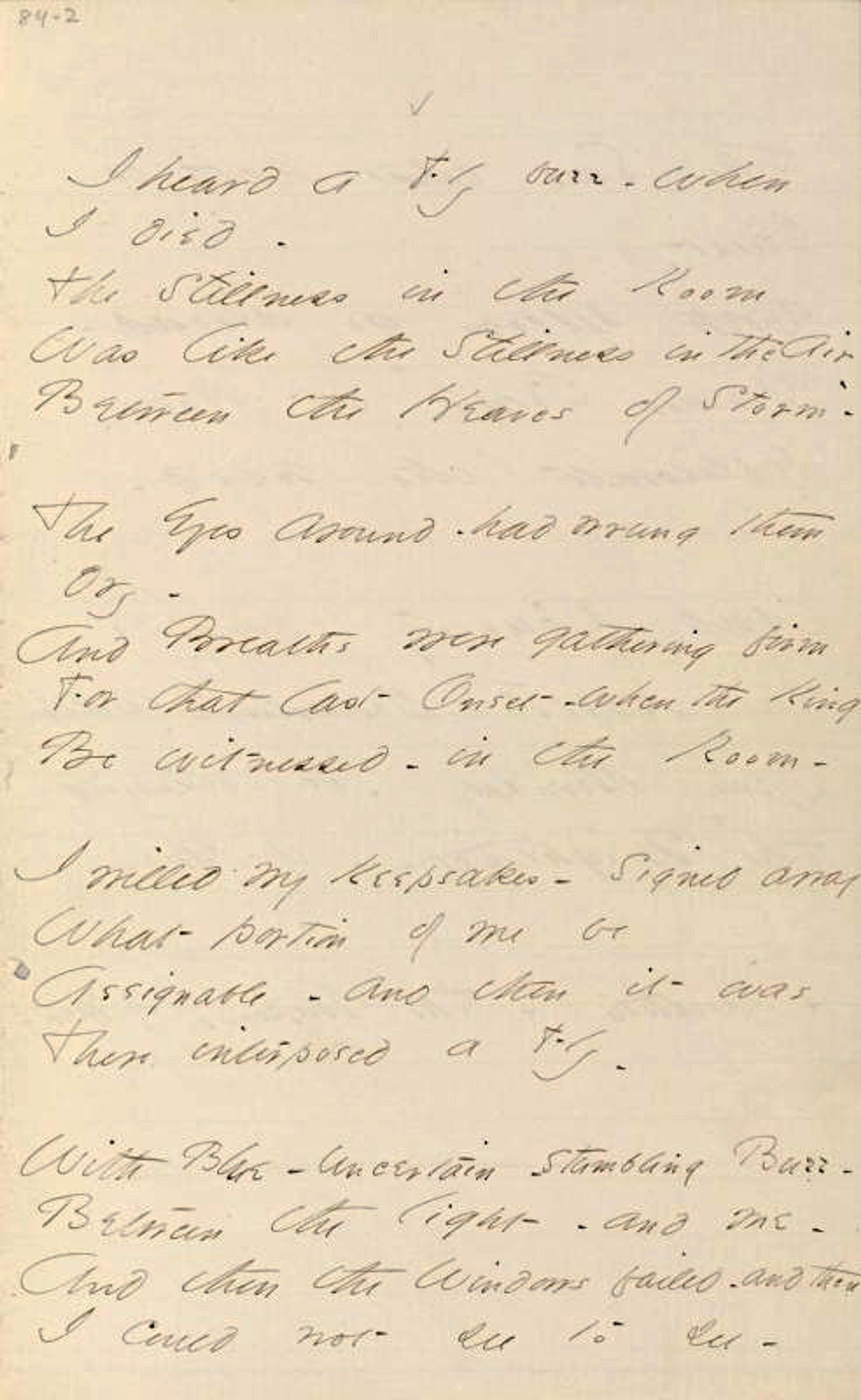

The original manuscript for ‘I heard a Fly buzz – when I died –’ (1896). Courtesy Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

To see such a perspective in play, consider the beginning of one of Dickinson’s best-known poems, her beautiful and haunting lyric about hearing a fly buzzing in the room at the instant of her own death. Dickinson wrote about 1,800 poems, but only 10 or so were published during her lifetime, and those were very heavily edited. ‘I heard a Fly buzz – when I died –’ was published only posthumously in 1896, when the extent of her poetic writings was discovered. It was included in a hand-sewn manuscript booklet, called a ‘fascicle’, thought to have been written circa 1863. It is an unconventional poem, even a radical one, its first stanza especially subversive:

I heard a Fly buzz – when I died –

The Stillness in the Room

Was like the Stillness in the Air –

Between the Heaves of Storm –

With this opening image, Dickinson invites us to occupy a specific and exact moment: the millisecond between life and death, exactly on the line between consciousness and unconsciousness: one foot in life, the other foot already out. Glossed simply, Dickinson’s opening line might be understood to say, I heard a fly buzzing around my body as I died, or as I underwent the process of dying. It is striking that, in the difficult moment just before death, Dickinson’s speaker manages to have such an alert and perceptive ear. And to report exactly what she hears: a simple fly buzzing around.

The power of Dickinson’s fly, strangely, stems from its capacity to anchor and calm her speaker’s experience rather than to unsettle it. The poem tells us that the speaker is quiet on the inside, content to be solitary and unattached. Her (and our) most common and naive hopes for the moment before death are totally and completely upended by the fly, for Dickinson’s speaker sees no tunnel of light, hears no angels singing, and perceives no bells ringing as she catches glimmers of the other side and prepares to depart.

Dickinson is so at ease in this poem with what we might call the reality of dying, a comfort that her inward isolation affords her, that she is able to look around unflinchingly and with courage. (Her own death in 1886 would be less peaceable – a protracted fight with disease.) We would expect the speaker in the poem to be overcome or overwhelmed, but she is so calm that she is able to bear the buzzing of the fly and to contemplate the finality it suggests: the fly outlives her to continue its vital, earthly buzzing around as she lies immobile, and it instantly signals the decaying of her body. And Dickinson’s insistence on the image of the fly – a winged terrestrial counter-angel – is also heroic. This is especially true in the context of her life in 19th-century Amherst, where she was raised in a devout Calvinist family. Her dissent from her family’s orthodoxy is an open theme in her poems, as in this from 1861:

Some keep the Sabbath going to Church –

I keep it, staying at Home –

With a Bobolink for a Chorister –

And an Orchard, for a Dome –

The image of the fly is similarly defiant in sharply deflecting the myths the Church teaches. What do we hear when we die? Flies, Dickinson manages to assert.

The most striking aspect of the isolation that inhabits Dickinson’s poems is that it allows her to expand the terrain that the first-person point of view can inhabit and traverse. We go places and see things inside of us in Dickinson’s poems that we’d miss in being engrossed in life. Like the millisecond that opens ‘I heard a Fly buzz – when I died –’, such perspectives let us imagine and inhabit spaces that we normally do not encounter. These imaginative crossings can expand our sense of who we are and what the world is. For example, in a beautiful and striking image for the loss of mental stability, Dickinson writes in 1862:

I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,

And Mourners to and fro

Kept treading – treading – till it seemed

That Sense was breaking through –

Here, she is at once the one observing the funeral, and the deceased – a perspective that requires bending out of shape our ordinary, first-person interior experience. In utter isolation, she writes further on in the poem, she sat with only ‘Silence’ as company, the two together ‘Wrecked, solitary, here –’. Dickinson is bracingly unsentimental about life without others. She does not miss the presence of people in the emotional landscape of some of her most poignant poems. She remains locked within herself, as though the inner terrain were already plenty to explore.

We learn from Dickinson that self-encounter can generate both creative energy and art. At a time when we’ve endured so much social distance, dwelled inwardly with ourselves, tracing and re-tracing our own borders, such lessons are nothing trivial.