When we hear the word ‘contagion’, our minds are immediately drawn to the viruses and bacteria spread through coughing and sneezing. This narrow view prioritises the biological, yet contagion is not unique to the spread of microorganisms. There is a growing body of scientific evidence showing that our internal mental states, including our emotions, might also be socially transmissible. Understanding the nature and dynamics of this emotional contagion is crucial in highlighting how social interactions might impact on our wellbeing. Within my field of research – adolescent development – this is a particular concern: approximately 75 per cent of all mental health conditions start before the age of 24, and adolescents are especially sensitive to peer influence. Exploring how mood spreads from person to person could help us better understand how mental illness develops.

In 1948, the inhabitants of Framingham, a town in Massachusetts in the United States, were recruited to participate in a large study. It was initially set up to better understand the causes of heart disease. However, decades later, two researchers noticed the unique and untapped potential of this data set. In addition to tracking heart disease, the original study had also collected information on depressive symptoms, such as low mood and hopelessness, and asked individuals to name their close friends and family. This meant that, in 2012, the researchers could map the social network of the whole town – to track which people spent time together – and then examine whether levels of depressive symptoms among friends were linked.

Using sophisticated mathematical models, they demonstrated that the inhabitants of Framingham were more likely to have depressive symptoms if a close friend did too. Rather strikingly, this effect held to three degrees of separation, with a depressed friend of a friend of a friend also increasing one’s chance of depression. Interestingly, it wasn’t just low mood that clustered among friends: the very same pattern was also found for people’s levels of happiness.

What we can’t know from these findings alone is whether this is due to true contagion or merely homophily, where similar people are drawn to one another in the first place, a case of ‘birds of a feather flock together’. The researchers investigated this by tracking mood changes across time and ultimately found that both depression and happiness did indeed spread like a contagion, even when accounting for how similar people’s moods were at the beginning. This suggests that your own mood really is affected by those around you.

Some research indicates that this effect is stronger for happiness than for low mood: one study in 2010 modelled the spread of mood over several years within Framingham, and found that positive mood contagion had a much longer-lasting effect than negative mood contagion. This is in line with the idea of infectious laughter: when we see or hear someone else laugh, we are far more likely to laugh ourselves. In another study from 2006, researchers asked people to listen to different sounds while lying in a brain scanner: some positive, including laughter, and some negative such as screaming. Both types of sound caused the brain region responsible for moving the muscles in our faces to become active. However, this activity was much stronger for positive sounds such as laughter, suggesting that these are more contagious than negative sounds.

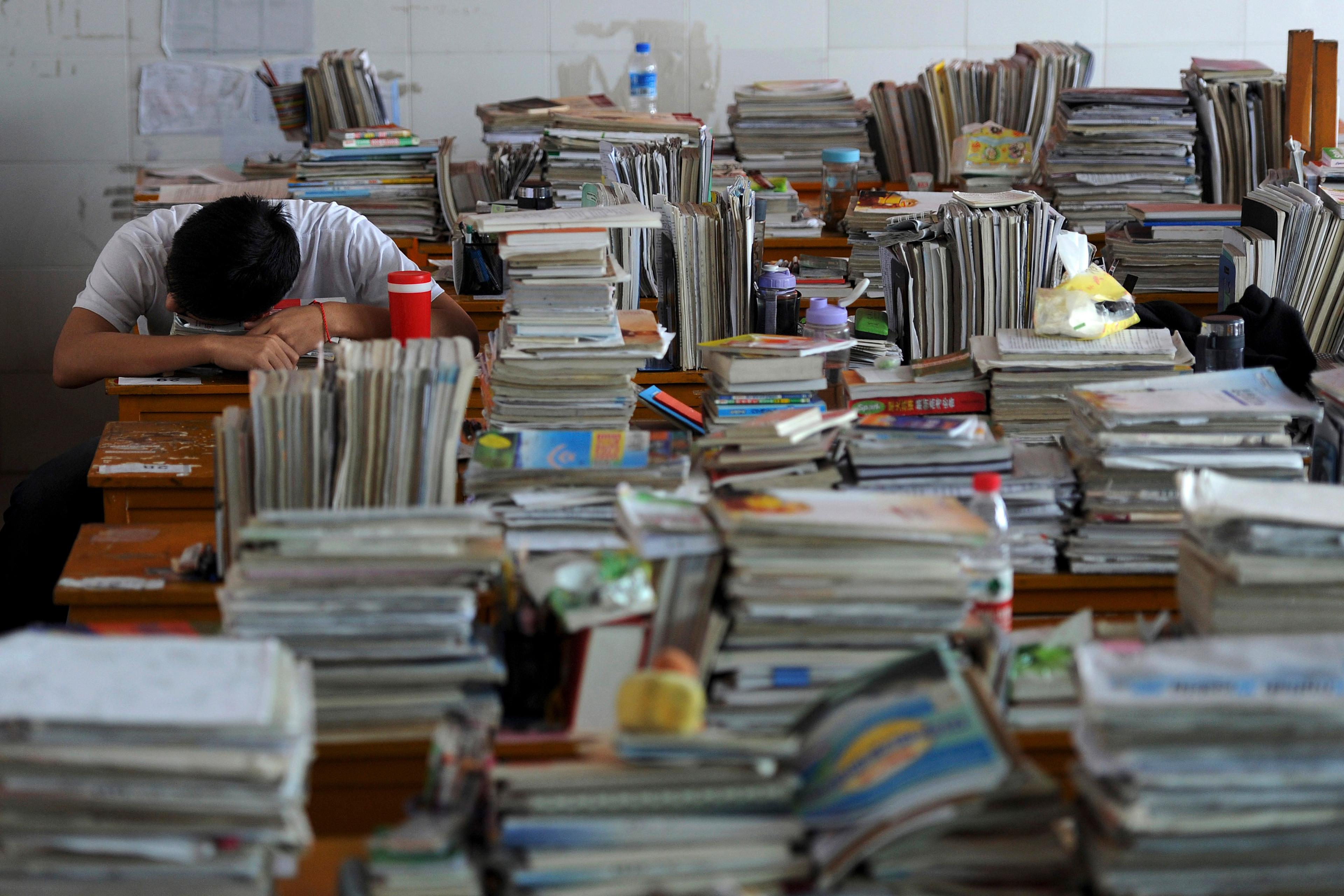

Mood can also spread among teenagers at school. In one study from 2015, researchers found that both happiness and symptoms of depression can propagate through the social networks of school friends. In addition, they found that having several friends who regularly experienced positive mood actually reduced the risk of teenagers developing depression. For those already depressed, having happy friends increased the chance of recovering over a six- to 12-month period.

Emotional contagion at this age is unsurprising: compared with adults, teenagers find emotions more difficult to control, and are also more likely to be influenced by their peers. Their susceptibility to emotional contagion reinforces the impact that friendships can have on mental wellbeing. Fostering supportive friendships should be a key focus for any intervention aimed at reducing the incidence of depression or low mood in young people.

These days, many of our social interactions occur via the internet, and our online social networks are also sites of emotional contagion. Consider a controversial large-scale experiment conducted on nearly 700,000 Facebook users in 2014. Researchers from Facebook and Cornell University in New York altered the content that Facebook users saw on their news feed without them knowing (hence the controversy). Individuals were selected to see either fewer positive posts or fewer negative posts on their feed. When people saw fewer positive posts than usual, they published fewer positive posts and more negative posts of their own; the opposite pattern was found for people exposed to fewer negative posts than usual.

Through online contagion, the effects of physical events can even be transmitted to people in faraway locations. In a study from 2014 conducted on millions of Facebook users over a period of three years, scientists from the University of California, San Diego, from Yale University and from Facebook explored how the weather affects the kind of content posted. On rainy days, the number of positive posts decreased, and the number of negative posts increased. On its own, this data tells us only that people post more negative statuses during bad weather – an unsurprising finding. However, the researchers discovered that rainfall also affected the nature of the posts made by friends in cities not experiencing rain. For every person living in a city hit by rainfall and who went on to post more negatively, the emotional expression of one to two friends living elsewhere was affected. Perhaps then, we should all feel less guilty about reaching for that unfollow button.

There could be a number of reasons why we’re affected by each other’s moods. One possibility is activation: when seeing or reading others’ expressions of emotions preps us to feel those emotions ourselves. This can help with social connection, but can be problematic when it comes to low mood. It’s also possible that we use others’ emotional responses in certain situations to guide our own responses, through a process called social appraisal – we look to others to understand what might be an appropriate way to feel or behave.

Another possible cause of emotional contagion is co-rumination. This occurs when we share our problems or difficult feelings with someone else, without coming up with a solution. Talking with our loved ones about our problems can be helpful, but going over a problem with someone else can lead to anxiety or low mood for us both if we focus too much on the negatives.

A surprising study from the Netherlands in 2012 found that emotions might even be transmitted via the smell of other people’s sweat. In this study from Utrecht University, women were exposed to sweat from men who had just watched either a scary or a disgusting film clip. The women were asked to complete a computer task while they unknowingly sniffed the men’s sweat, and the researchers recorded their facial expressions. The women exposed to the sweat of the men in the scared group were more likely to open their eyes in a fearful expression, while those who sniffed the sweat of the disgust group were more likely to scrunch their faces in repulsion. This suggests that information about some emotions – fear and disgust – can, in part, be transmitted via the nose.

Contagion is undoubtedly more than a biological phenomenon. Unlike the spread of viruses, emotional contagion is not necessarily a bad thing. Although some aspects of low mood might be contagious, happiness is too – possibly even more so. Knowing that mood can ripple through close groups like this has important implications for how we behave. On a personal level, this might affect whom we want to spend time with. On a bigger scale, it could encourage leaders and managers to model positive attitudes and consider the kind of norms that are established among their teams. Finally, emotional contagion can inform interventions to support people’s wellbeing. Investing in our positive social relationships appears to reduce our own chances of developing depression and could also have a positive rippling effect throughout our social networks. Seeking out and fostering positive friendships might not only improve our own mental health but could benefit the mental health of others too.