Your sense of who you are is deeply entwined in the stories you tell about yourself and your experiences. Storytelling is a big part of how we develop a view of our lives, says Jonathan Adler, a psychologist at Olin College of Engineering in Needham, Massachusetts. If you’ve ever struggled with low self-esteem, you’ll know just how important it can be to try to find a positive story to tell about yourself.

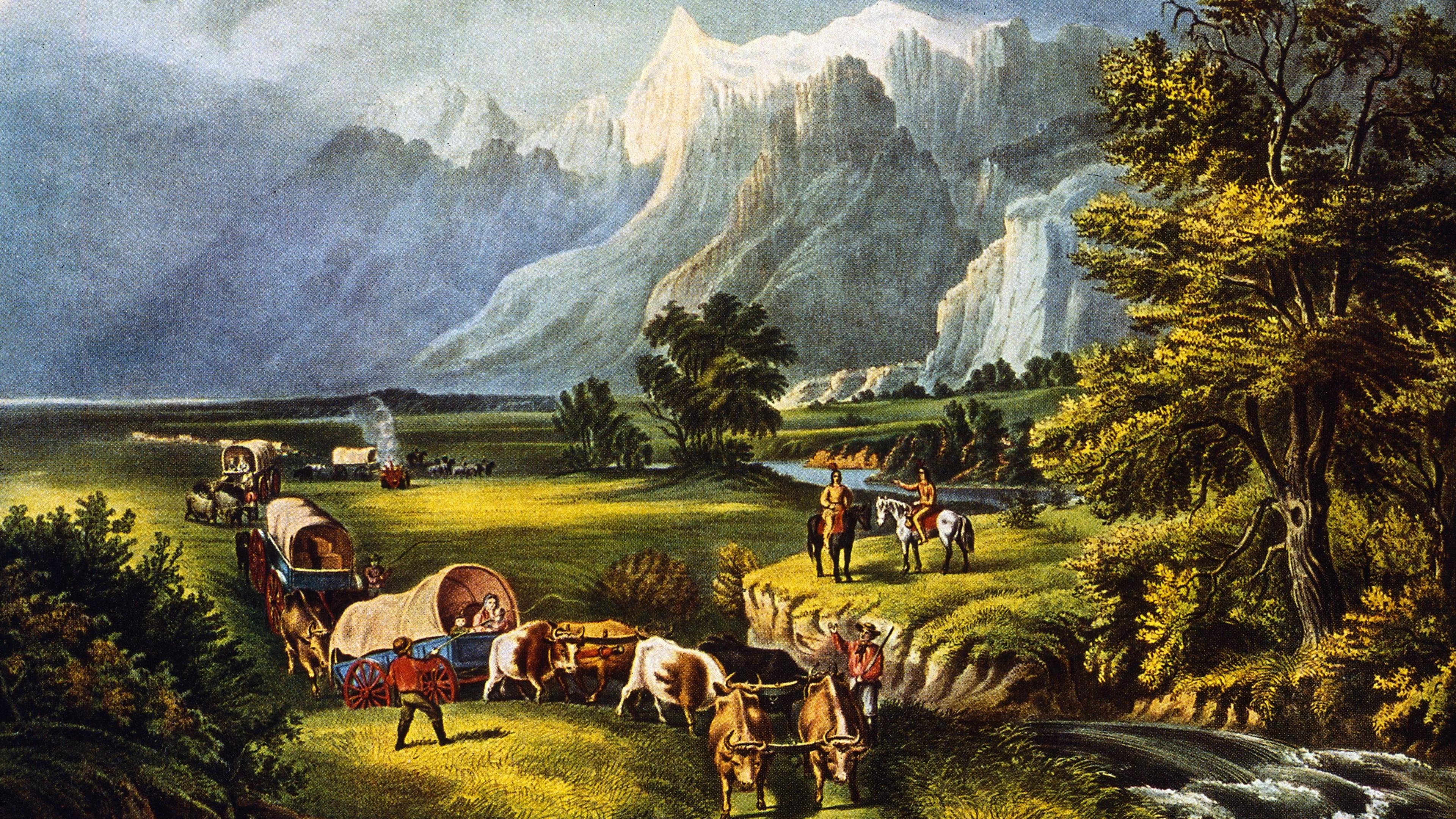

This was certainly true for me as a young girl. When I was old enough to understand, my mother occasionally talked about how, on her side, we were descended from Meriwether Lewis, of the 1804 Lewis and Clark Expedition to map the western territories of the United States. I recall her providing only one piece of evidence for this – her mother had named one of her sons Lewis after the explorer and spelled it the way his name was spelled, instead of the alternative (Louis). This was enough to convince me, and I clung to this story to help me cope with an otherwise bleak home life.

My parents suffered from what back then we called alcoholism, with all the turmoil that can entail. They would start drinking before dinner most nights, and when I would beg them not to, they’d berate me. If I was hoping my two brothers and I would become close to compensate for the chaos at home, I was out of luck. They were both pretty wild growing up. My older brother joined a motorcycle group as a teen and then enlisted in the Marines. His military career didn’t last long, however, and his life wasn’t much better afterward. My younger brother was a risktaker and always in trouble.

I had no self-esteem back then. But believing this story – that I was related to a famous explorer – lifted me up. There was one person I was related to whom I could be proud of (and by association, I felt I could be proud of myself).

With a little research, I’ve discovered I’m far from alone in finding solace in these kinds of family stories. Take Michael Harper, executive director of the Salvation Army in Portland, Maine, and a pastor for the organisation. When Harper was a kid, he heard he was descended from John Winthrop, a governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the 1600s. Harper’s parents divorced when he was eight, and he, his mother and his five siblings moved 30 times during his childhood while trying to manage on welfare. ‘It was one apartment after another. I could never establish roots and always felt like I didn’t belong,’ he says.

In his 50s, Harper was able to confirm through the Genealogy Roadshow, which aired on PBS from 2013 to 2016, that the family legend was true: he was descended from Winthrop, among other famous people. ‘It made a big difference,’ Harper recalls. Being able to trace that thread gave him ‘a great deal of satisfaction’.

‘When I was living in Boston,’ he tells me, ‘after I learned that I was descended from someone famous who landed there from England, I joked that, when I drove through the city, I felt like I owned the place. It made me feel very proud, and that thought has never left.’

Being related to a famous explorer was similarly my ace in the hole for gaining significance. Until it wasn’t. When I was in fifth grade and my class started studying the Lewis and Clark Expedition, I couldn’t wait to tell my teacher and classmates about my enviable lineage. However, I could tell by my teacher’s nonchalant nod and lackadaisical response that she didn’t believe me. I just wanted to get up and run out of the room.

It’s a problem of not recognising one’s own talents, capabilities, limitations and potential

Amy Morin, a licensed clinical social worker in Florida and host of the Mentally Stronger podcast, has practised therapy for more than 20 years. She tells me that anyone whose self-worth is dependent on someone else (or being related to someone else), like I did, is going to be on ‘shaky ground’.

‘You might later discover you aren’t actually related at all, which could affect your self-esteem [even more]. Or, you might feel deflated when someone else isn’t as impressed as you think they should be,’ she says.

‘It’s important to develop self-worth based on who you are as a person, not who people in your lineage were. Everyone’s family has people who have struggled and people who have accomplished things,’ notes Morin.

Barbara Becker Holstein, a psychologist in private practice in New Jersey whose specialties include positive psychology and self-esteem, sees this as a problem of not recognising, and probably needing to learn how to recognise, one’s own talents, capabilities, limitations and potential.

‘The more we understand and develop our own potential, the more we can see that who we may or may not be related to is interesting, even fascinating. But … critical to our own development – and what is most important – is to realise you are unique and have much to offer in life.’

I grew to understand that my parents’ absence in our lives was likely a big factor in my siblings’ and my development (or lack thereof). Living with four people whose lives had gone terribly wrong was so sad sometimes that I could hardly stand it, and I was embarrassed and ashamed when others found out, even though I knew intellectually that I was not a reflection of my family.

Thankfully I found a different story to tell about my family and about my life. This rewriting of my story has parallels with the process of ‘narrative therapy’ – which has to do with finding more positive ways to interpret and tell our life experiences.

Alongside his university role, Adler is also chief academic officer of the Health Story Collaborative, an organisation in Boston that organises events and gathers resources to help people find and tell their own healing narratives.

We’re born without words, let alone stories, Adler explains, ‘and storytelling is a skill we learn from other people. So it always comes from outside at the beginning. Indeed, even when we tell a story to ourselves, we then put that story out into the world and get feedback on it. In a way, then, our stories are always these negotiations with other people.’ Sometimes they unfold directly through dialogue with the people in our immediate lives, such as our family or friends – but, other times, they’re broader cultural stories.

‘In the particular phenomenon of [looking to a famous person for self-esteem], it seems that there’s some cultural storyline, or maybe in specific instances there’s an actual family storyline that is somehow resonating for the person,’ Adler says. He doesn’t necessarily think of storytelling as all positive or negative; it’s something we all do that can have positive and/or negative consequences for us.

Annie Brewster, a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, is the founder and executive director of the Health Story Collaborative. She says ‘It [can be] hard and painful to have to “rejigger” our stories and retell them, but it can also be health-promoting. Through the challenge, it can also cause us to see ourselves more fully.’ Ultimately, she concludes, ‘it’s a developmental and appropriate shift if we can have more of our internal story come authentically instead of trying to fit into another narrative from the outside such as looking to link with a famous person.’

Watching my two brothers screw up gave me two more examples of how I didn’t want to be

This resonates with the way Harper and I have both found good endings to the stories we have told ourselves about our lives. Despite his difficult start, not only does Harper look back on an impoverished childhood without bitterness, he praises his mother for ‘holding her brood of six together’. Also, in choosing a career that is the epitome of helping others, he’d likely be the first to say he gets back more than he gives.

Like him, I, too, have chosen a positive path – and told a different story – when I could have ended up quite differently. Watching my two brothers screw up gave me self-discipline and two more examples of how I didn’t want to be. Determined not to experience difficulties with addiction like them, I saw their lives as a lesson. I told myself I would make good decisions and not be waylaid. I began plotting a new narrative.

I was teaching in my mid-20s when, in a night class for an MBA degree, a classmate who worked at AT&T mentioned that there were openings for writers in her department. I interviewed, was hired as a contractor, and didn’t go back to classroom teaching that September. After a few years, I started getting up at 5am to write occasional essays and articles for magazines before leaving for work.

Then, one day around that time, I saw a business column in The New York Times and realised there was an opportunity. I called the paper and asked to speak to the column’s editor. He had me write a sample column that got published, and that was the start of a dream job. For 20 years, I freelanced for the business section and eventually I earned my own column. I wrote a book with an addiction specialist, Sober Siblings: How to Help Your Alcoholic Brother or Sister – and Not Lose Yourself (2008). Today I ghost-write for executives and write executive columns for several publications.

I still think of that incident in fifth grade. Years later, my cousin went on a road trip to research our family’s ancestry. I learned about a reunion of Lewis’s descendants to whom we were supposedly related, and I contacted the reunion organisers in the hope that my cousin and I could attend. I sent my cousin’s findings to a genealogist there to prove our lineage, with the outcome that I learned – definitively – that we were not related to the Lewis family after all. Today, I can laugh about our family legend being false. After all, I found a better story to tell. And if I could say something to that fifth-grader today, I would tell her: ‘You’re special just the way you are. And don’t let anyone make you feel otherwise.’