In the United States, although attention towards race and identity is ubiquitous, this focus often remains narrow – seeing racial identity as a rigid, permanent trait clearly defined for all. Yet growing immigration rates and racial intermarriage have left many with racially ambiguous positions in US society. Accordingly, burgeoning research on ‘racial fluidity’ has sought to better understand these shifting contours of race. In recent research, I take one step in this endeavour, evaluating how the same Americans change the way they racially self-identify over time.

A sizable obstacle in studying such individual-level race change is the data it requires. Researchers often turn to surveys to easily and reliably capture self-reported racial identification. But, for the question of how one’s self-classification changes over time, typical surveys conducted at one point in time no longer suffice. Instead, this enquiry demands reinterviewing the same people at two different points in time – which is referred to as panel surveys – resulting in different ‘waves’ of data-collection on the same questions. Such data for representative samples of the adult population are notoriously in short supply, though they still exist.

To complicate matters further, some panels take the aforementioned narrow view of racial identity to heart, and opt against asking it across its waves; in one case, a survey explicitly pointed to a view of racial identity as unchangeable as its rationale for this choice. Despite this challenge, I was still able to gather five unique, high-quality panel surveys for studying race change. These data sources are popular among both political scientists and sociologists, covering national samples (and reinterviews) of the US population across the past two decades. The earliest started in 2000 (and reinterviewed subjects in 2004), while the latest went from 2016 to 2020.

The goal in this study was to paint a comprehensive descriptive portrait of individual-level racial identity change in the US, for both the entire population and initial racial subgroups. For example, across the five surveys, I wanted to know what percent of all Americans change their race over the span of the panel, what percent of Americans who initially identify as white change their race, what percent of initial Black Americans do so, and so on. Each of the five surveys asked about respondents’ races in slightly different ways, but, because the format was identical within each survey (from the first to second wave), establishing change due to shifting identities – and not shifting question formats – remained achievable. Similar patterns also appeared across each format, providing a layer of robustness to the findings.

So, how often do Americans change their racial self-identifications? On average across each survey, about 8 per cent do. Not every data source yielded the same number, with a low of 5 per cent and a high of 12 per cent. While these levels of change may seem small, given prior assumptions about racial identity’s stability, they are hardly insignificant – a small but meaningful portion of Americans change how they racially see themselves over time. Moreover, this population-wide level of change masks a substantial variation in how often certain racial subgroups undergo identity change. Among those who initially saw themselves as white, about 4 per cent typically altered their identities. However, among Americans who did not originally identify as white, an average of 20 per cent across the five surveys changed their identities from the first to last survey waves.

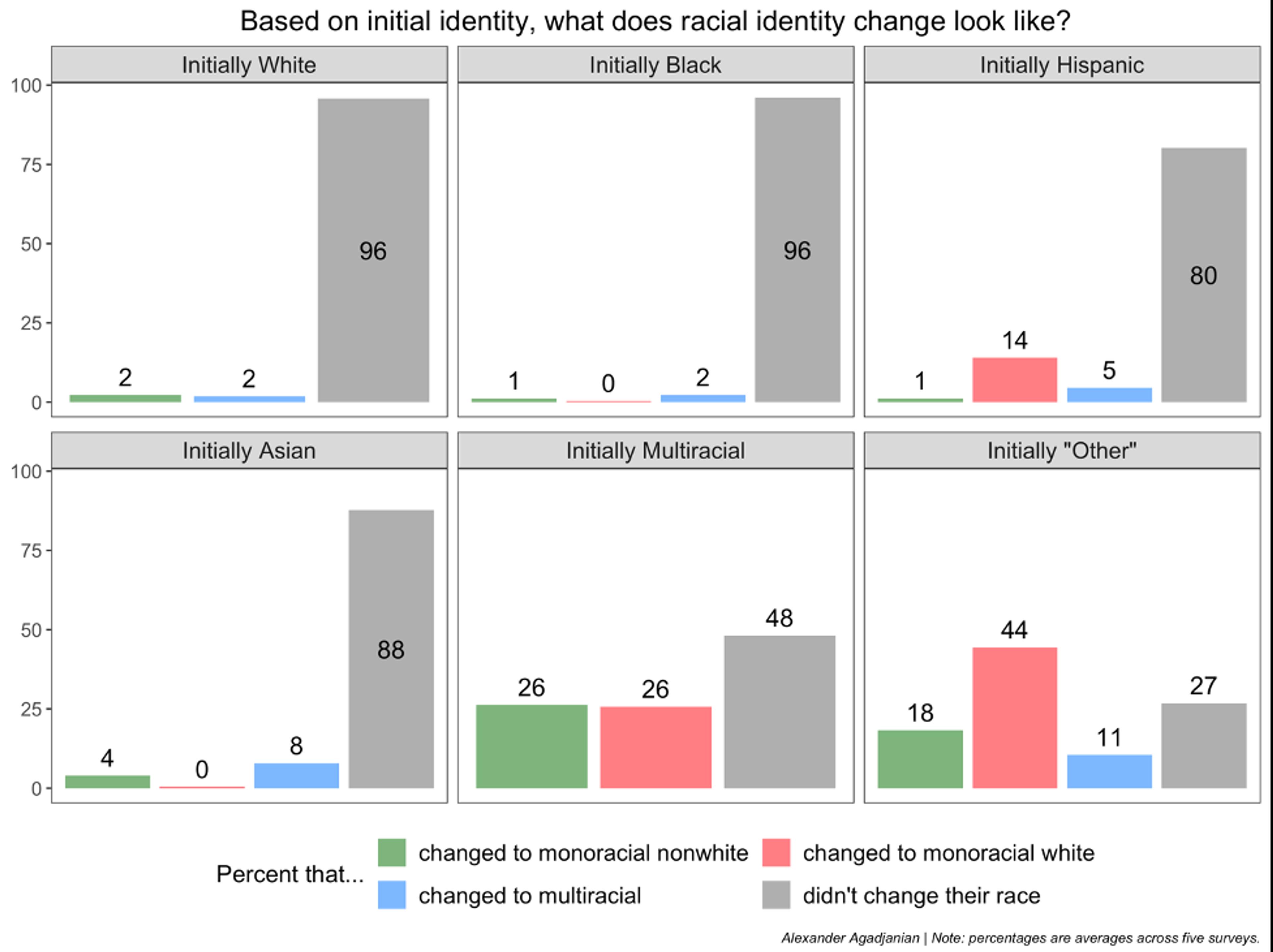

The accompanying graph drills down more precisely into subgroup dynamics and provides a clearer picture of what individual-level race change looks like. The six panels of the graph correspond to groups based on survey respondents’ initial reported racial identities. The most familiar of these are groups of Americans who initially identified as either only white, only Black, only Hispanic, or only Asian. Two other initial identity groups also contained large enough samples for analysis: 1) multiracial identifiers (those selecting multiple races or identifying as ‘mixed’ race); and 2) people who eschewed the offered racial categories and selected ‘Other’. Within each initial group, the graph shows the distribution of racial identities – averaging across the five surveys – years later. People either didn’t change their race, changed to ‘monoracial nonwhite’ (identifying with only one nonwhite category), changed to ‘monoracial white’ (identifying only as white), or changed to multiracial.

The data here add valuable nuance to the earlier dynamics of racial identity change. For example, we see that among Americans initially identifying as white or Black, nearly all (96 per cent) identify the same way years later. This is perhaps unsurprising in light of the ingrained Black/white dichotomy in the US. But instability in identity gradually increases when moving to relatively newer groups in US society. Those who originally identify as Asian retain the same race at the lower rate of 88 per cent; multiracial identification is the most common choice for those Asians who move. Initial Hispanic identifiers change even more – only 80 per cent identify as Hispanic years later, with many of the movers expressing a white identity over time. (Note that this 14 per cent rate of change to white is partially driven by one survey, though, even when accounting for this outlier, Hispanic movement into whiteness is more common than for the other two minority groups.)

Unfortunately, because of sample size limitations, it is hard to glean much more information about shifting identities from groups like original Asian or Hispanic identifiers, such as which nationalities may drive change most. Future research will clarify these important leftover questions, though other analysis offers some clues: for example, a Pew Research Center study in 2017 found that retention of Hispanic self-identification among Americans with Hispanic ancestry is tightly linked to how long their families have resided in the US.

Finally, those for whom traditional racial categories don’t always fit well exhibit far and away the highest degrees of racial identity turnover. Fewer than half (48 per cent) of Americans initially identifying as multiracial still express dual identities at a later point in time. A majority, instead, drift into monoracial (ie, single race) identity attachments over time, with equal shares later identifying as only white or only one nonwhite category. This is notable: despite rapidly increasing intermarriage and children with mixed-race parents, many gradually shed multiracial labels over time. One consequence of this is that the US population may be more multiracial – and internally racially complicated – than we currently appreciate.

Meanwhile, Americans who initially select ‘Other’ as their race undergo the highest degree of identity change of all the considered initial groups. In other words, roughly 73 per cent no longer identify as ‘Other’ in later years. Curiously, a plurality of this group changes to a singularly white identification over time; perhaps many in this group always had white racial backgrounds but chose to sometimes defy the racial identity question asked by surveyors.

As with any type of research, limitations exist. For example, the data cannot confirm whether such shifts in identity are permanent, or whether racially malleable groups move to and from different group identities depending on the context in which they find themselves. More research is needed on this front.

Questions also remain as to what precipitates an individual to change how they racially define themselves, though scholarly work has gradually begun to provide answers. For example, changes in social position and status have emerged as one catalyst of race change, while economic incentives represent another possible cause. Other work has uncovered a political basis for racial and ethnic change, rooted in voting behaviour and partisanship. For example, in my past work with a colleague, changes from multiracial and Hispanic identities to white identification proved strongly related to voting Republican for the first time in 2016 – which, notably, meant support for Donald Trump.

In sum, it’s worth reflecting on the importance of assessing racial fluidity and identity change in the US. Race remains a powerful shaper of various aspects of one’s life. But if it’s malleable for growing racially ambiguous populations, it means that social, economic and political outcomes are not just consequences of racial identities but can also be their causes; racial differences in US society do not have just one source. This dynamic inevitably shapes how people see themselves fitting into society and social relations; how they fill out racial identity information on Census, school, work, and political forms; and how national demographic trajectories unfold. In short, internalising racial fluidity offers novel clarity on contemporary racial dynamics in US society, and their future.