I’m sitting in a bar in Berkeley with friends, next to a stranger on a plane to Germany, on the floor of a hospital records room in a tiny town in Western Massachusetts.

I’m 35, 29, 22.

I’m talking to someone who asks if it’s right that I don’t have kids – after all, didn’t my ancestors sacrifice and persevere for my existence? Don’t I owe their descendants a future? Thinking like the scientist I once was, aren’t I obligated to perpetuate their genes?

How could I end my family line?

I didn’t have an answer at age 22 – I thought maybe it was some kind of responsibility to keep my particular set of chromosomes in play. At 29, I had a more assured reply: I knew that my own life path, my work, my art, my love of freedom, was no match for some never-insisted-upon dictate from my family to have a child.

In that, I am lucky – there have been zero guilt-trips from my aunt, father or grandparents. Strangers have been less sympathetic. I’ve been yelled at on a plane for my choice to be childfree by a random fellow traveller, and guilted by acquaintances. But not those closest to me.

At 35, the question just angered me – by then I understood there was never a right answer for the newly met neighbour or nosy colleague. They just wanted to tell me I was wrong, that my uterus was somehow my ancestors’ vessel for progeny to come.

The idea that we, who choose to be childfree, are betraying our relatives has come up in softer, indirect ways, too – a new friend said she felt free to not have kids because her sister had them, but that she might feel differently if she was an only child. A college roommate told me he had his child mostly because his parents would have been ‘devastated’ if he hadn’t, and he just couldn’t ‘do that to them’.

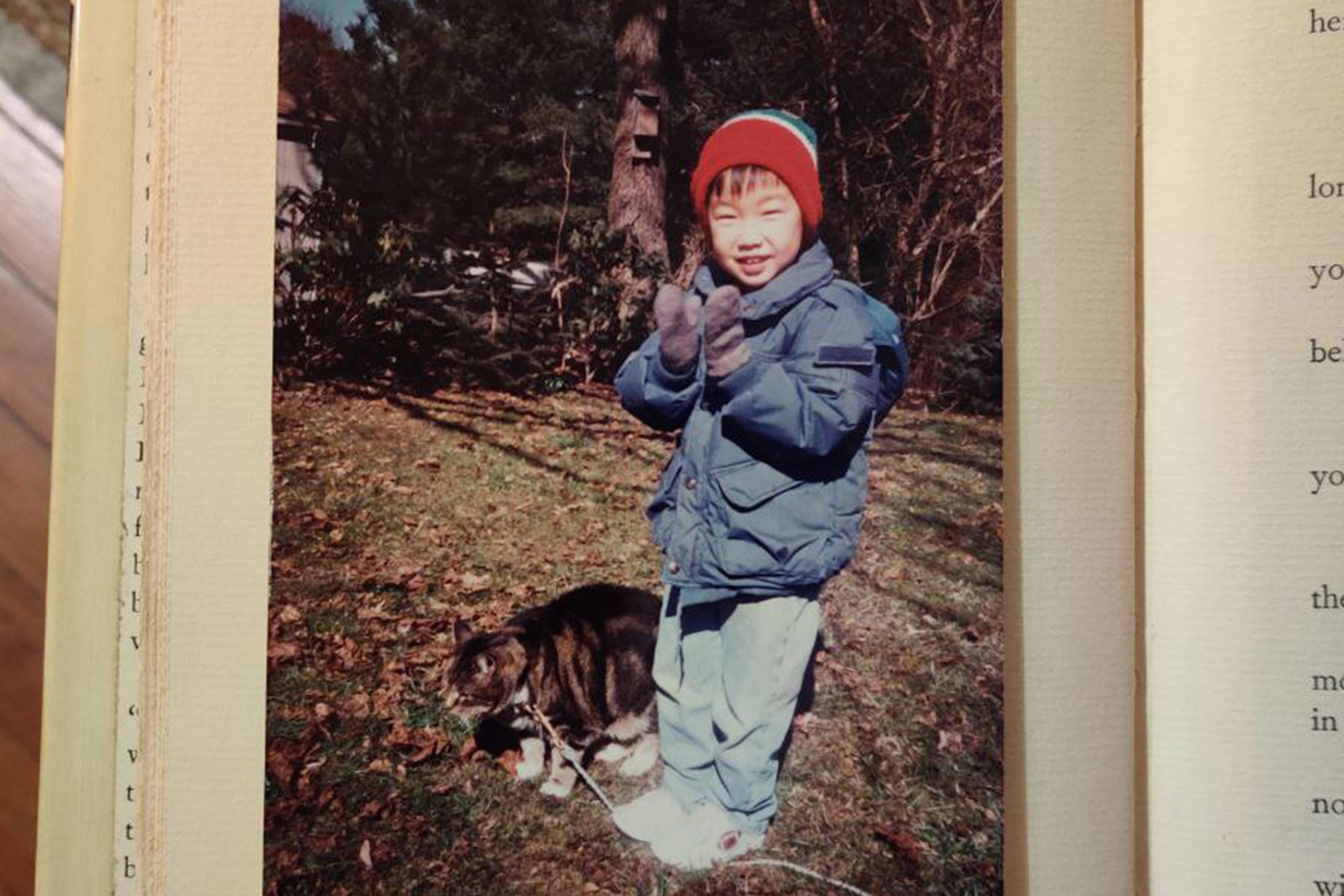

Even if you are secure in your choice to be childfree, guilt about ending the family line can still run deep. Your cultural background will likely influence to what degree. The part of my family line that stops with me is specifically my Armenian branch. My Scottish Lebanese grandmother was an only child, and her first husband was the son of Armenian refugees. They had two sons in New York City in the 1940s, but only one – my father – was biologically his. I’m my father’s only child, in turn.

That makes me the only link to those Armenian great-grandparents; and I’ve been asked if I don’t feel a little guilty that they fled genocide, only for their genes to be ended by my choice.

I’m hardly alone in considering what my ancestors went through for my eventual existence: Gail Saltz – a professor of psychiatry at the New York Presbyterian Hospital and the Weill Cornell Medical College, and a psychoanalyst with a popular podcast – says that while people who have always known they didn’t want kids usually don’t give it as much thought: ‘People that come to the choice a little later seem to be more concerned and unsure about what their doubts mean’ –especially in the context of passing down a legacy.

Saltz says that, among historically persecuted groups, there may be extra pressure to have children as a coping mechanism for the trauma of uprooting and removal or even extermination of ancestors. From a psychological standpoint, she explains, the sense is often: ‘We survived and thrived, there are more of us now, and you did not succeed in eliminating us – we overcame it. And there are certain groups where that defence takes on cultural and religious meaning at times.’

While others may worry about legacy in general, I’m compelled to wonder about the survival of those genes. How much does one genetic line and my choice to be childfree really matter on a planet teeming with 8 billion souls? Was I destroying something biologically fundamental – not just a cultural through-line of some kind – by choosing to discontinue part of my family’s genetics?

I decided to find out.

Human beings share about 99 per cent of our DNA with chimpanzees – so the vast majority of our genes are working to build and maintain a basic hominin. Zooming in on Homo sapiens’ genes in particular, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) online curriculum on the subject states that the genetic difference between any two humans is just 0.1 per cent. This is because humans are a fairly young species and so don’t have as much genetic variation as most of the other species on Earth that have been around much longer.

That humans have such close genetic similarities to each other is one of the hallmarks of our species. Though it may seem like there’s a wide variation in genes across humanity, the diversity in phenotypes (how genes look when expressed, giving us skin, hair and eye colours, etc) is misleading. In fact, according to the NIH, ‘genetic variation around the world is distributed in a rather continuous manner; there are no sharp, discontinuous boundaries between human population groups.’

The vast majority of genetic variation – about 85 per cent – exists within human populations (say, all the people in Spain). Just 15 per cent of genetic variation occurs between populations, so residents of Spain are more different from each other than they are from residents of a similar-sized country like Kenya. Human beings are a ‘continuously variable, interbreeding species’ and this understanding of genetic difference is one of the main reasons many biologists see race as a social construct, not a biological one.

But, for most people, the idea of a family line is about a few individuals – ourselves and close family. So, while it’s true that even though humans are all quite similar compared with many other species, we are also each genetically unique: there is enough variation between human genomes that, according to the NIH, ‘no two humans, save identical twins, ever have been or will be genetically identical’.

Still, while each of us can be distinctly identified by our specific DNA, there’s a reason why after five to seven generations those differences mostly blend into the general genetic mix of humanity (with the exception of mutations that are carried on a specific gene, like those that cause certain diseases). That’s because, with each generation, more ancestors come online: we have two parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents, and so on and so forth, all the way down to our species’s appearance on Earth.

So, when I end my family line, unless I have a totally new, unique mutation that will then disappear from the gene pool (unlikely, according to experts), all the genes that make up who I am will still exist in other people’s DNA strands. What’s unique about me – and you – is simply the particular combination of those genes. Ashleigh Griffin, professor of evolutionary biology at the University of Oxford, explained: ‘What you’re really doing is shutting down the lineage that has that exact combination of genes.’ In that way, the layperson’s understanding of genetics and family line is correct. As a childfree person, I’m ending something particular.

I asked Griffin if it mattered – genetically. But the way she answered made me think that this probably wasn’t really a science question after all: ‘There’s nothing objectively wrong with a family line going extinct, right? It’s a subjective thing. Do you think that’s a problem?’ I said I didn’t, but wondered if it might have any larger implication. Since they are my genes, she said simply: ‘If you don’t think it’s a problem, it’s not a problem, right?’

Right. I don’t think my particular set of genes is important or valuable enough to change my life and commit to the lifelong job of parenting to continue them. I’m more interested in contributing to the great big human experiment in other ways. I hope my work will lead to a better future for human beings, and that I can contribute something else of value outside my genes.

Griffin explained that this kind of thinking is a common evolutionary tactic that makes genetic sense, too. Genes are always passed along via either cooperation or competition. Different species have different tactics. Meerkats, a species of adorable mammal inhabiting the Kalahari Desert of Africa, live in cooperative groups with just one breeding pair. ‘The adults that don’t breed help raise the offspring produced by the dominant pair,’ says Griffin. All those helper meerkats are imperative to the breeding couple’s success and, because they’re related to the couple, their genes get passed along too, just less directly.

This is an evolutionarily successful technique, because meerkats are not the only mammals to breed in some kind of cooperative way like this – if it didn’t work well, the species would die out. It’s not necessary for every fertile meerkat to reproduce, and these animals are more successful if they don’t. This has such fundamental benefits for the species that organise this way that Griffin has even found this behaviour in bacteria, where some will expend energy in ways that don’t benefit the individual but help the group.

This cooperative action among related animals, called kin selection, is favoured by natural selection and foundational to social behaviour across groups in all kinds of life. ‘You are enhancing the reproductive success of kin, rather than the number of offspring that you produce yourself,’ Griffin explains.

My non-genetic contributions might be more useful than putting my body through a process that repels me and forces me into work I don’t want to do. (And, having done plenty of childcare during my teen years, I know how much work it is.) We’ve had just a small window of time during which a large percentage of human women have been able to choose whether to have children. We are still learning what that means to the individual, and the group. But perhaps some among us resemble the cooperative meerkat more than the competitive primate, making non-gene contributions that protect our species’s legacy and power the future for all.