William James, the father of Western psychology, in 1902 defined spiritual experiences as states of higher consciousness, which are induced by efforts to understand the general principles or structure of the world through one’s inner experience. At the core of his view of spirituality is what we might call ‘connectedness’, which refers to the fact that individual goals can be truly realised only in the context of the whole – one’s relationship to the world and to others.

Traditionally, this spiritual state has been described as divine, achievable through contemplative and embodied practices, such as prayer, meditation and rhythmic rituals. Indeed, this higher state of consciousness and connection has been reported in many spiritual traditions, ranging from Buddhism to Sufism and Judaism to Christianity. However, recent neuroscientific research shows that the same state can be achieved by secular practices too. Scientific and creative epiphanies with their accompanying ecstatic states characterised by a sense of unity and bliss are similar to religious experiences, with both involving a higher state of presence and observation. Many geniuses, such as Albert Einstein and the mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan, reported spiritual-like states during their revelations or breakthroughs. But these don’t have to be the rare experiences of a chosen few. They can be reached in daily life. As the Nobel laureate and poet Czesław Miłosz put it: ‘Description demands intense observation, so intense that the veil of everyday habit falls away and what we paid no attention to, because it struck us as so ordinary, is revealed as miraculous.’

I’m a neuroscientist and, among other things, I study the way that spiritual states are reflected in the brain and other parts of the body. Spiritual practices have been shown to be closely linked to self-awareness, empathy and a sense of connectedness, all of which can be correlated with the frequency of brainwaves as measured by electroencephalogram (EEG). Studies using EEG have demonstrated how ‘fragmented’ or out of step our whole brain activity can be much of the time, suggestive of conflicts between our behaviour, thinking, feeling and communication. On the other hand, expert meditators demonstrate more ‘harmonious’ brain waves, which could be indicative of greater synchrony or connectivity within and across different neural areas. In short, spirituality, similar to love, has physiological effects in the brain and body, and EEG provides a window on these changes.

What’s more, research suggests that we can do more than just measure this kind of activity. We can also train our brains to behave in a more ‘aware’ way by engaging in activities that facilitate greater connection or neural synchronisation. Higher synchronisation – imagine a large group of brain cells singing together – has been found following the practice of different contemplative paradigms, such as meditation and prayer (creating, as it were, slower ocean waves, now growing calmer and calmer). One way of interpreting this is that neuronal synchronisation enhances our brain ‘harmony’ or ‘integrity’ – achieving a state in which the brain works in a more congruent way, adopting a more global perspective. Other findings point to the psychological consequences of this state – greater neuronal synchronisation tends to enable a greater ability to make moral judgments and problem-solve creatively.

Neuronal synchronisation also correlates with feeling more self-connected, which can, in turn, further increase empathy, creativity and social effectiveness. In two words, it’s associated with greater self-awareness, which has many practical benefits. For instance, the psychologist and author of Insight (2017) Tasha Eurich wrote in the Harvard Business Review in 2018 that people with greater self-awareness are more confident, make sounder decisions, build stronger relationships and communicate more effectively. The self-aware also receive more promotions, have more satisfied employees, and achieve more profitable companies.

You might be concerned that taking a neuroscientific approach to profound, ineffable spiritual experiences is reductionist. But another perspective is that the scientific exploration of such experiences could reveal the mechanisms enabling us all to achieve these states even in the most mundane moments, such as waiting in traffic. Scientific discovery could turn seemingly subjective experiences into unified (and unifying) understanding. Simply put, I’ve seen how spirituality can be experienced in the lab! Let me share some examples with you.

Most of my research over the past two decades is linked to a movement meditation called Quadrato Motor Training (QMT) that demands both coordination and mindfulness. Practitioners alternate between dynamic movements and static postures, while dividing their attention between their body in the present moment and its location in space. QMT requires a connection between the ‘external’ world and the inner realm by requiring the participant to be intentionally aware of both inner and outer ‘worlds’ simultaneously.

In our research, we found that QMT improved cognitive flexibility. For example, in thinking about a simple glass, most people will associate it with the act of drinking. But following QMT training, additional ‘worlds of content’ can open up – the glass can be viewed as ‘the holy grail’ or a hat. In fact, our study showed that a seven-minute QMT session increased cognitive flexibility by 25 per cent, compared with other simpler kinds of movement or verbal training. What’s more, EEG measures showed that the enhanced cognitive flexibility associated with QMT training was also accompanied by increased brain synchronisation of the kind previously related to relaxation, attention and a flow state. Some might say QMT also fosters spirituality.

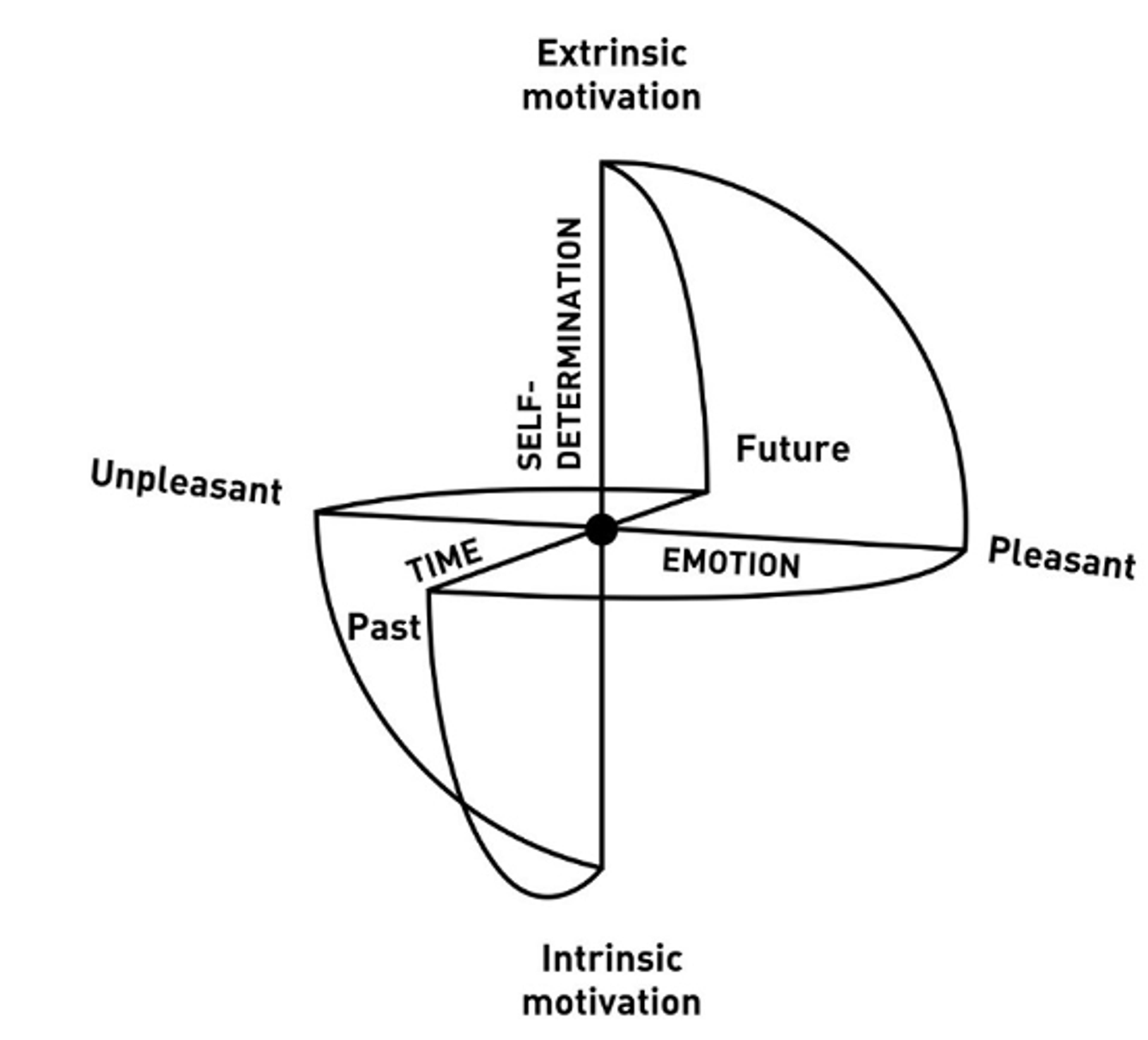

What else helps to produce neural synchronisation? Well, perhaps surprisingly, being in a space similar to a sensory-deprivation chamber, with little external stimulation, also impacts on neuronal synchronisation. Such was the idea behind the OVO chamber (uovo is Italian for ‘egg’, describing the space’s shape), created by Patrizio Paoletti, one of the leading teachers of meditation, based on his ‘Sphere Model of Consciousness’ (stated briefly, the model describes a spherical matrix that maps on to our subjective experiences, ranging from ordinary automatic habits to higher states of consciousness achieved in contemplative practices; see figures 1 and 2 below).

Figure 1: Sphere Model of Consciousness

Figure 2: The OVO chamber, created by Patrizio Paoletti, is in the shape of an egg, based on his Sphere Model of Consciousness

My colleagues and I have found that OVO-immersion leads to increased neuronal synchronisation in the insula, a brain area related to empathy as well as bodily self-awareness. In turn, this was found to be accompanied by an increased sense of ‘absorption’ (akin to that feeling you get when overwhelmed by the beauty of a sunset, as you fully and voluntarily engage your attention in the experience). Absorption is also closely related to spirituality, meditation and empathy, likely because all involve openness to self-altering experiences and voluntarily increasing awareness.

Although most of us don’t have access to an external ‘egg’ chamber, we can place ourselves at the centre of our own ‘sphere’ in daily life. By rooting ourselves, listening to our highest aspirations, and paying closer attention to our breathing, to the people we love and to the present moment, we can transcend the here and now to create a more ‘spherical’ life that changes our focus from basic needs and fears to values. This is further accompanied by an intentional shift toward a clear ‘goal’ state, represented by the centre of our inner sphere in Paoletti’s model. In this sense, spirituality can be seen as actions that are not separate from daily life, but rather congruently connected to its different aspects – the body, family, career, friendship, relationships, finance and society.

As well as finding Paoletti’s Sphere Model of Consciousness useful in my neuroscience research, I also use it as a practical instrument with which to observe myself. As spirituality is closely related to one’s state of consciousness, self-awareness and neuronal synchronisation, the more one’s consciousness is elevated, the more one feels the connectedness of things. Imagine you’re out driving and notice the sun setting. Is your next thought about the traffic, or are you awed by the glorious sunset and the daily planetary dance we all share? Now imagine the same drive. Someone recklessly cuts you off and zooms away. Is your first reaction to get upset and start chasing them – risking yourself and others? Or do you remain calm, with your heart rate the same as before the car overtook you?

In both examples, the latter option involves engaging a more mature, present part of ourselves in the current once-in-a-lifetime moment – being fully connected to the experience of the sights, the sounds and the scents. This is the kind of experience some call spirituality, namely the interconnectedness of being. In contrast, each time we react involuntarily, we aren’t anchored in our centre, but controlled by a more automatic state not chosen by us, and therefore we’re less connected both within ourselves and to the greater good.

For me, a big part of spirituality is overcoming daily challenging situations with calm and care. When we lose it, for instance, what exactly are we losing? Nothing less than our selves. We all lose it sometimes, but we can lose it less often by continually reconnecting to our best selves and to each other.

Recently, while preparing for an online conference, I shared some of my data showing increasingly greater levels of relaxation among novice, intermediate and expert meditators. My curious 17-year-old daughter said: ‘Mom, I know how to meditate. I’m an intermediate practitioner, right?’ I replied: ‘Well, as you see by these graphs, there is a big difference between knowing how to meditate and actually practising it regularly. Imagine some stairways you can climb to reach the sky. You have the means to get there, but now you need to keep climbing.’

As a neuroscientist, knowing that brain change is possible (even among grown-ups) keeps me optimistic and motivated in my research. Through simple non-invasive techniques, we can all train and monitor our spirituality and, in turn, live more vibrantly.

This Idea was made possible through the support of a grant to Aeon+Psyche from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. Funders to Aeon+Psyche are not involved in editorial decision-making.