In a recent TikTok video captioned ‘Just another day in Germany’, a man walks with a scowl on his face and bumps roughly into another person with tattoos and piercings, who is wearing a leather vest. As the first man turns, his expression changes into a bright smile, and he says: ‘Entschuldigung!’ meaning roughly ‘My bad!’ The man who got bumped, and his two tough-looking friends dressed in all black, reply congenially, ‘Alles gut!’ (all is well).

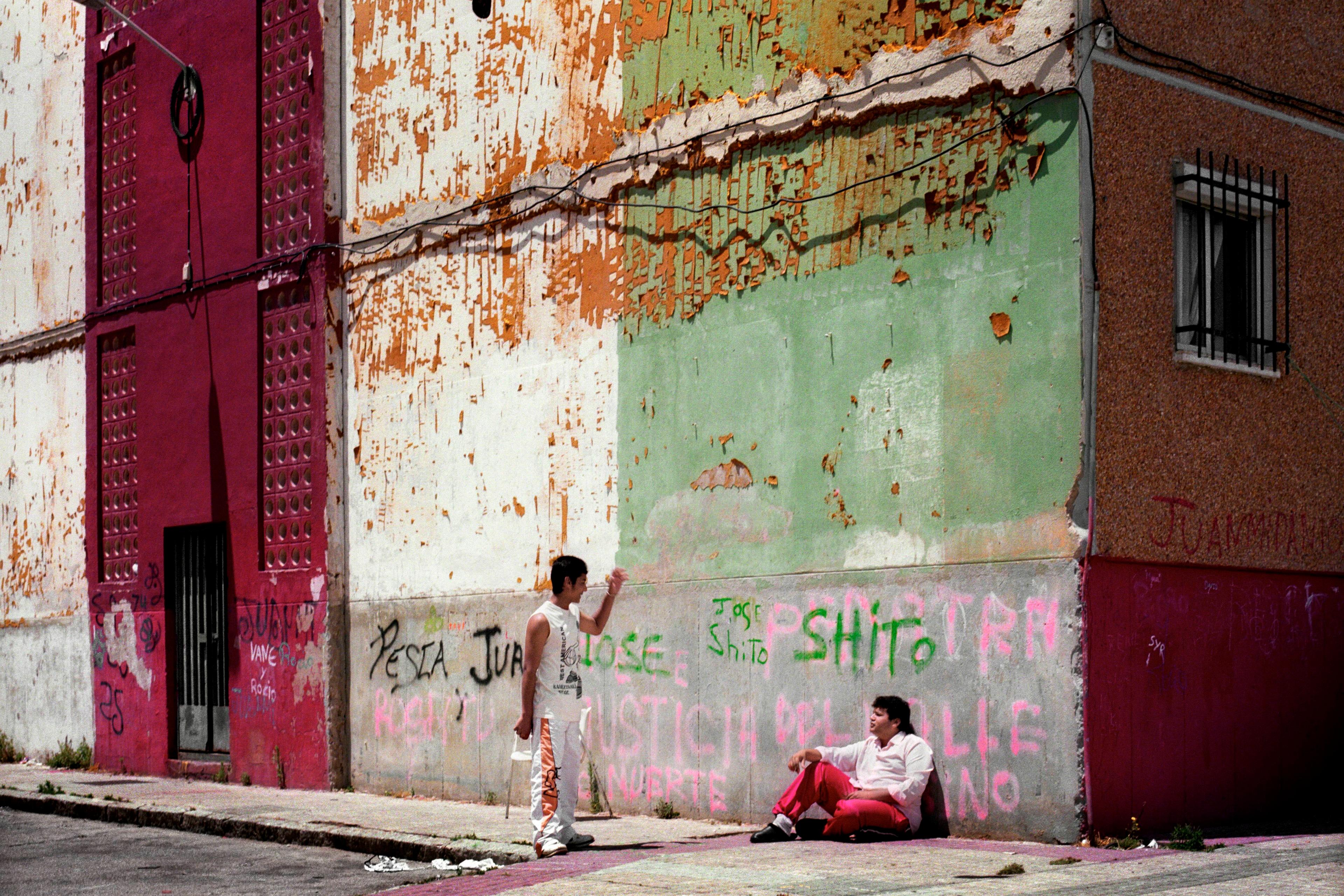

Millions of people liked this video because of the charming contrast between how unfriendly the people appear at first, compared with their actual behaviour. It also inadvertently characterises a tension within the field of psychology about how we make judgments about others. Do we assume what people are like based on what they do (a process that psychologists call ‘the spontaneous trait inference effect’), or based on stereotypes related to their age, gender and so on?

A recent study in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology put this question to the test by examining the influence of stereotypes on the ‘spontaneous trait inference effect’. It raises interesting questions about the impressions we form of each other every day and whether the stereotypes we endorse about others (whether explicitly or without realising) are as influential as is often assumed.

If you saw someone helping carry groceries or getting a good grade on a test, it’s likely that you would automatically, and often unconsciously, assume traits about their overall personality: that they are friendly or smart. Or let’s say you saw a person on the street screaming at someone else. ‘You might spontaneously, even without having an intention to judge that person, think that person is aggressive because of that behaviour,’ says Jana Mangels, a psychologist at the University of Hamburg in Germany, and first author of the paper. That would be ‘spontaneous trait inference’ in action.

But when we form impressions of other people, we do so using different, sometimes contradictory, information, Mangels says. People also hold stereotypes about others: assuming that because a person appears to belong to a particular group, they will have certain traits that they associate with that group. Let’s go back to the person screaming on the street and imagine that it was a woman. If an observer believed the stereotype that all women are calm and docile, would they still spontaneously assume this woman was aggressive based on her behaviour? Or would their stereotypical beliefs about women override the spontaneous trait inference effect?

Past research has found that stereotypes can clash with the spontaneous inferences observers make based on people’s behaviour, and in some cases even override them. For instance, a study from 2003 found that people who were asked to infer traits about a ‘garbage man’ doing well on a science quiz were less likely to assume he was ‘smart’ compared with a professor doing well on a science quiz. Other work has found that people are more likely to spontaneously infer traits that align with behaviours fitting a particular stereotype, rather than ones that were inconsistent with stereotypes. Yet in their new series of experiments Mangels and her co-author, Juliane Degner, found the opposite: that the spontaneous trait inference effect held strong, even in the face of contradictory stereotypes.

The pair used what’s called a ‘probe recognition paradigm’. Their participants read statements about someone’s behaviour, such as ‘John gets an A for the test’, and then they had to look at a list of words – such as ‘brave’, ‘smart’, ‘gets’ and ‘test’ – and for each one indicate as fast as possible whether or not it had appeared in the previous statement. Included in the word list would always be two trait words that weren’t in the original statement, one of which people might automatically infer applied to the person based on their behaviour – ‘smart’ in the previous example. It’s been established in earlier social psychology research that because of the ‘spontaneous trait inference effect’, people are generally slower to reject the implied trait (‘smart’ in this case) as having been in the earlier statement, compared with how quickly they reject other trait words that were not implied by the behavioural statement (‘brave’ in this example).

Participants seemed just as likely to assume the old man was strong (based on his behaviour) as the bodybuilder

In each of four studies, Mangels and Degner built on this basic research design by attributing the initial behaviours to people from different social groupings that have stereotypes attached to them. For example, the researchers attributed the behaviour ‘picked up a stack of boxes like it was nothing’ to different people on different trials of the experiment: either a bodybuilder picked up the stack, an old man, or a person named Leslie (used as a neutral control). The researchers’ goal was to see if the stereotypes held by participants about old men and bodybuilders would get in the way of, or bolster, the spontaneous trait inference effect – which in this example was intended to trigger the inference that the person was ‘strong’.

To the researchers’ surprise, only one of the experiments showed that stereotypes had any effect on spontaneous trait inference at all, and even then the effect was small. To zoom in on the example above, the participants seemed just as likely to assume the old man was strong (based on his behaviour) as the bodybuilder. ‘We didn’t find what we expected,’ Mangels says. It suggests that the influence that stereotypes can have on spontaneous impressions may not be as strong as previously thought, at least not when people are evaluating unambiguous behaviour.

It’s important to understand these tendencies because, outside of the lab, when we make these sorts of fast judgments about each other, there can be lasting consequences. ‘We know from other research that these [spontaneous] impressions are hard to change,’ Mangels says. Simply being more aware of the psychological processes that underlie the impressions we form of others could help us to be more reflective about the assumptions we make – and more ready to counter our spontaneous impressions in the cases when we find out they’re not accurate. (In this vein, previous research has shown that deliberately putting ourselves in other people’s shoes can help prevent us from jumping to conclusions about their traits based on snippets of their behaviour.)

The new findings are based on a single series of lab studies and of course they don’t mean that people don’t ever use stereotypes when making judgments about others – stereotypes are still powerful influences in many contexts. Still, ‘it might be that they’re not used as we expected in instances where the behaviours that we observed from other people are quite unambiguous,’ Mangels says.

This means that as long as people interpret another’s actual behaviour, they might make judgments about them based more on what they were doing, than what their associated stereotypes are. Or as Mangels put it in the title of her paper: ‘When the punk wishes you a great day, he still appears friendly.’