In 1848, Edgar Allan Poe proclaimed that readers would no longer waste their time on long poems: ‘the day of these artistic anomalies is over. If, at any time, any very long poem were popular in reality, which I doubt, it is at least clear that no very long poem will ever be popular again.’ It’s not hard to see why long poems aren’t the most fashionable form of literature today. Poetry demands a sustained close attentiveness that is already difficult to achieve; long poems, which take up whole books with hundreds or even thousands of lines, combine this intense concentration with arduous duration. If reading a sonnet is hard work, why put yourself to the trouble of reading an epic?

But, on one point at least, Poe was wrong. Long poems really had been popular, with wide and diverse readerships, at various times in literary history. Is this a kind of reading that we should try to recover? There are signs that the long poem might be making a comeback. Contemporary poets are experimenting with this seemingly archaic and unwieldy medium. Counterintuitively, long poems might actually be the perfect form for the present: they can represent the sheer unmanageable scale, the vast and messy confusion, the epic ambivalence, of the 21st century.

Many of the world’s oldest surviving works of literature are long poems, or fragments of long poems, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh (Mesopotamia, c2000 BCE), the Iliad and the Odyssey (Greece, c750-725 BCE), and the longest poem ever written, the Mahabharata (India, c400 BCE), which is roughly 10 times longer than the combined Greek epics. These long poems were probably transmitted orally for centuries before being written down and attributed to individual poets (Sin-leqi-unninni, Homer, and Vyasa, respectively). These long works were composed in verse rather than prose – that is, they use particular poetic features such as repetitions, parallelisms and metrical rhythms, which distinguish them from prose works from the same periods – in part because these features would help generations of poet-singers to remember the poem. Later on, the Old English poem Beowulf (c650-1000 CE) may have evolved in a similar way.

In late medieval and Renaissance Europe, one of the most popular genres of the long poem was the chivalric romance. Whereas epic poems are traditionally focused on reaching a specific endpoint (the conclusion of a war or a journey, or the foundation of a civilisation), the romance is more drifting in its structure. Poems like Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (1516-32) and Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (1590-96) follow legendary knights from the courts of Charlemagne or King Arthur as they wander, without much direction, in search of quests and fantastical adventures. Writing a long poem, whether epic or romance, carried a tremendous amount of prestige in the early modern period. The best-known and most celebrated example in English is John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), an epic retelling of the Fall of Man through Satan’s temptation of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.

It’s easy to suppose that these long poems were successful because the novel – the long fictional narrative in prose – wasn’t a widely practised form yet. But ‘the day of these artistic anomalies’, as Poe put it, the heyday of the long poem in English, was in the 18th century, the same period as the so-called ‘rise of the novel’. Perhaps because they were competing with prose narratives, 18th-century long poems tended away from telling stories altogether. Instead, poets wrote philosophical treatises or even ‘how-to’ manuals in verse. The Fleece (1757) by John Dyer, for example, taught its readers, over 2,700 lines, how to farm sheep. (‘Be gentle, while ye strip/The downy vesture from their tender sides,’ and so on.)

One of the bestselling books (of any genre, not just poetry) of the whole 18th century was James Thomson’s The Seasons (1730), a sprawling poem with no plot, but thousands of lines of gorgeous natural description. Although it is little read today outside of university classrooms, The Seasons went into a new edition almost every year, up to 1880. Thomson’s account of autumn’s melancholy abundance, its ‘breath of orchard big with bending fruit’ and its ‘fading, many-colour’d woods’, directly inspired later Romantic poetry on the season by William Wordsworth, John Clare, and John Keats.

Keats commented in 1817 that the long poem was a ‘test of [the poet’s] Invention’, and invention was in Keats’ view ‘the Polar Star of poetry’. He also thought that long poems were nourishing for readers as well as writers:

Do not the Lovers of Poetry like to have a little Region to wander in, where they may pick and choose, and in which the images are so numerous that many are forgotten and found new in a second Reading: which may be food for a Week’s stroll in the Summer?

For Keats, a long poem isn’t a painful ordeal. It’s a space in which to wander like a knight-errant of romance. It’s a space to which you can return in your memory or in a rereading.

We tend to expect that novels, even the most structurally avant-garde, should be read from beginning to end, in order. Even if you go back to reread and focus on a particular section, you keep the larger structure in mind. Long poems, on the other hand, have always been broken up into smaller units that can be extracted and anthologised. Novels are greater than the sum of their parts; long poems’ parts are greater than their wholes. According to Keats, you can dip into a long poem and ‘pick and choose’ the sections you enjoy most. There’s a kind of freedom, an autonomy, in this way of reading.

There are several reasons for this difference in how we read novels and long poems. The division of verse into lines invites us to see long poems in terms of their constituent units. There is also the common assumption that poetry offers greater local intensity than prose. We tend to assume, rightly or wrongly, that one stanza from a long poem will be more rewarding (and more exhausting) than a single paragraph from a novel.

Another reason that readers like Keats are willing to ‘pick and choose’ parts of a long poem is that we don’t expect long poems to tell stories so clearly as novels do. Of course, novels can play with narrative: they can repeat, digress, scramble timelines, and do all those weird structural things that long poems had already been doing for thousands of years. But we still expect a novel to have some semblance of a unified plotted story – if it doesn’t have one, it might be labelled a ‘prose poem’ instead. Some long poems have plots, others gleefully disregard them.

In 19th-century Europe and North America, the novel overtook the long poem as the most popular and highly regarded long literary form (hence Poe’s disdain). Many of the long poems that were published, such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh (1856) and Robert Browning’s The Ring and the Book (1868-9), are often called verse novels because they so closely imitate the novel’s conventions.

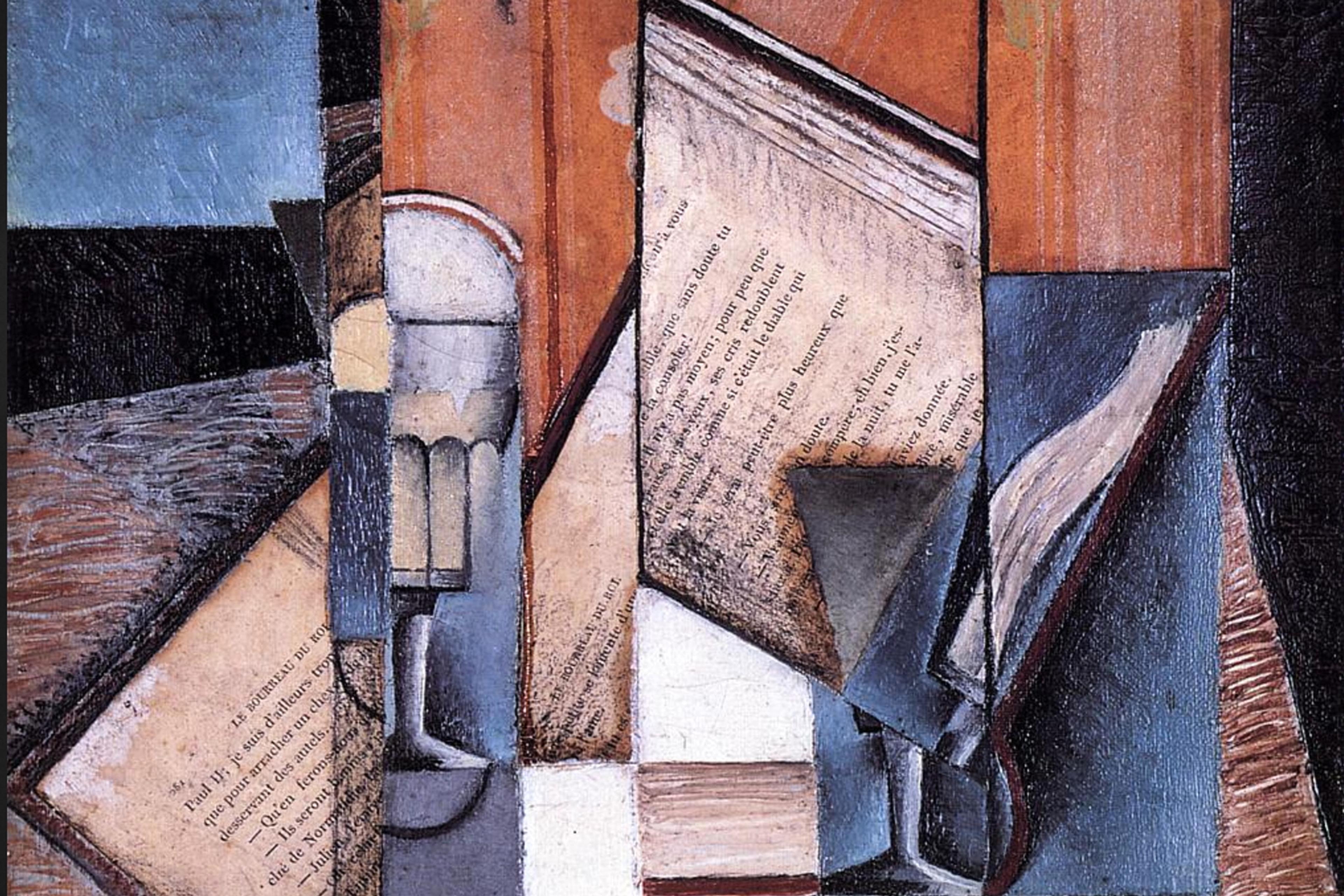

But in the early 20th century, modernist writers found potential in the quality of the long poem that Keats had admired 100 years earlier: its status as a whole that is nevertheless always on the verge of fragmentation, at risk of splintering into individual elements or images. Modernist epics like Hart Crane’s The Bridge (1930), The Cantos (1915-62) by Ezra Pound, and H D’s Helen in Egypt (1961) emphasised the fractured nature of their forms, so that it’s not always clear whether they are long poems or sequences of shorter poems. ‘Series on series, infinite,’ writes Crane, describing waves in the sea but also his vision for his poem, ‘enclose/This turning rondure whole …’ Modernist poets found that the old forms of epic and romance could be adapted to articulate the tension between unity and multiplicity, coherence and chaos, continuity and rupture, that they perceived in contemporary life. It’s no surprise, then, that interest in the long poem renewed in the years following the First World War, as Oliver Tearle argued in 2019.

In the 21st century, poets have returned to the long poem in order to write about historical atrocities. Anna Rabinowitz’s Darkling (2001) addresses the Holocaust through a series of brief pieces that are brought together into one whole through the use of acrostic: the first letters of the left-justified lines in the poem spell out Thomas Hardy’s poem ‘The Darkling Thrush’ (1900). The form of the long poem is used to express the sense that experience and memory can only ever be fragmented, but that hope emerges from the act of gathering those fragments.

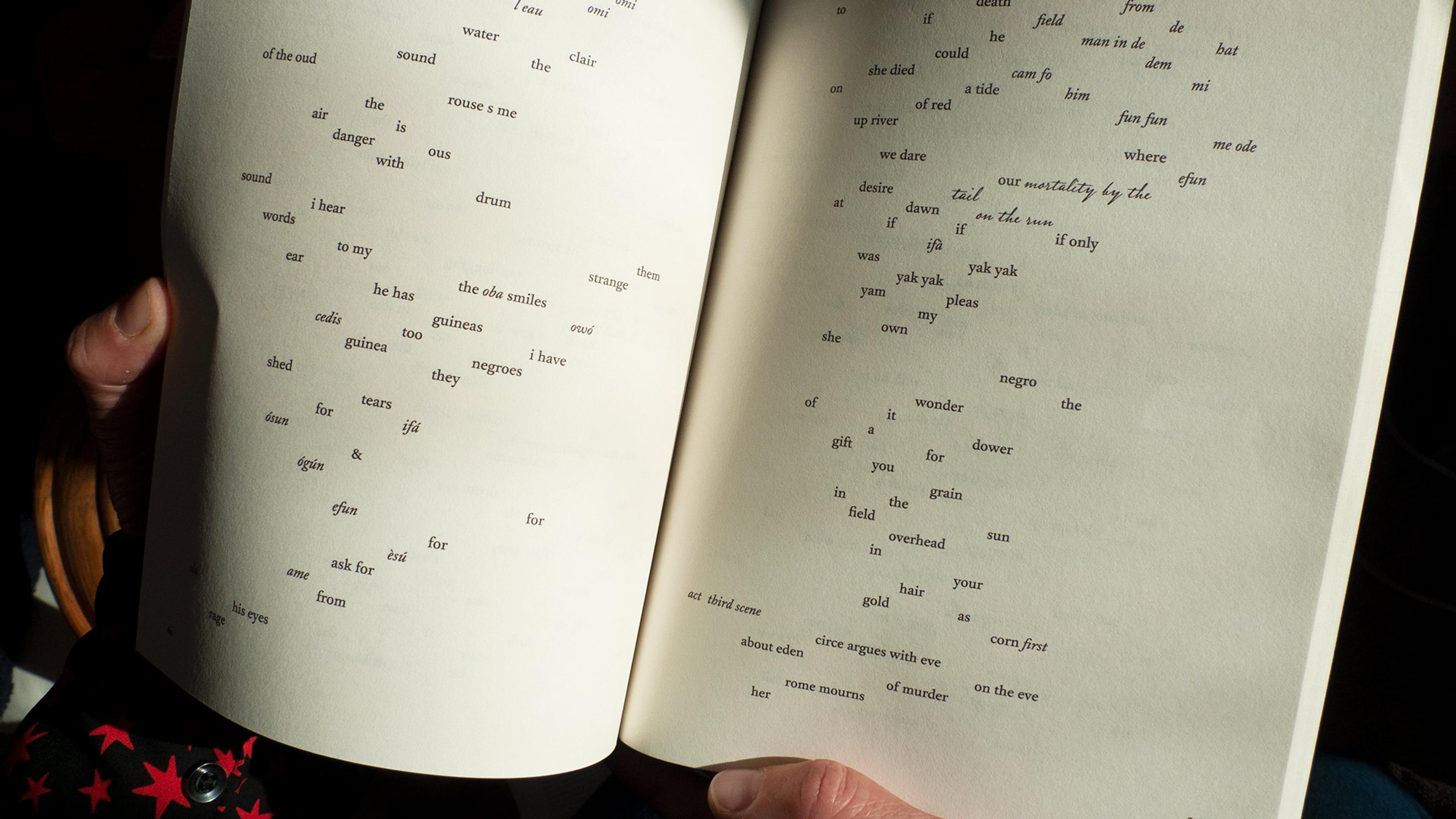

M NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! (2008), too, is a book that appears at first to be a sequence of short poems, themselves broken up into shards of words and letters, but is really one long poem, in this case about the mass murder of some 130 Africans on the slave ship Zong in November 1781. Days and Works (2017) by Rachel Blau DuPlessis reimagines the ancient Greek long poem Works and Days by Hesiod in order to think about numerous crises of modern life, including the climate crisis, poverty, and war. Classical long poems have also been recast for new audiences through translation. The first of Pound’s cantos is a translation from a part of Homer’s Odyssey. And the Odyssey itself was translated by Emily Wilson in 2018 to great acclaim. One of the world’s oldest long poems, with its themes of war, violence, masculinity, and misogyny, never wants for relevance.

The long poem can approach such vast themes because it does not claim to cover everything, or try to condense its material into a neat plot. Instead it suggests interconnections and resemblances, and invites readers to do our own creative work in piecing its parts together.

John Berryman remarked in The Dream Songs (1969) – itself a long poem composed of smaller ‘songs’ – that ‘The only happy people in the world/are those who do not have to write long poems:/muck, administration, toil: …’ We might assume that the same tedious labour is required of the reader, not just the writer, of a long poem. Sitting down to Paradise Lost, The Cantos or Zong! is not really comparable to a lazy summer stroll as Keats suggested. But there is something in between toil and leisure that long poems offer their readers, as well as their poets. Perhaps Poe was right and the days of long poems finding truly mass audiences are over; but, for those who take the time, long poems offer the reader a space in which to wander in search of meaning, a personal quest to find coherence in the turmoil of history.