Today I wondered What is the worth of a day? Once, a day was long. It was bright and then it wasn’t, meals happened, and school happened, and sports practice, maybe, happened, and two days from this day there would be a test, or an English paper would be due, or there would be a party for which I’d been waiting, it would seem, for years. Days were ages. Love bloomed and died in a day.

So writes Heidi Julavits in The Folded Clock: A Diary (2015), a looping, enveloping memoir in which, as with much of life, both a lot and also very little takes place.

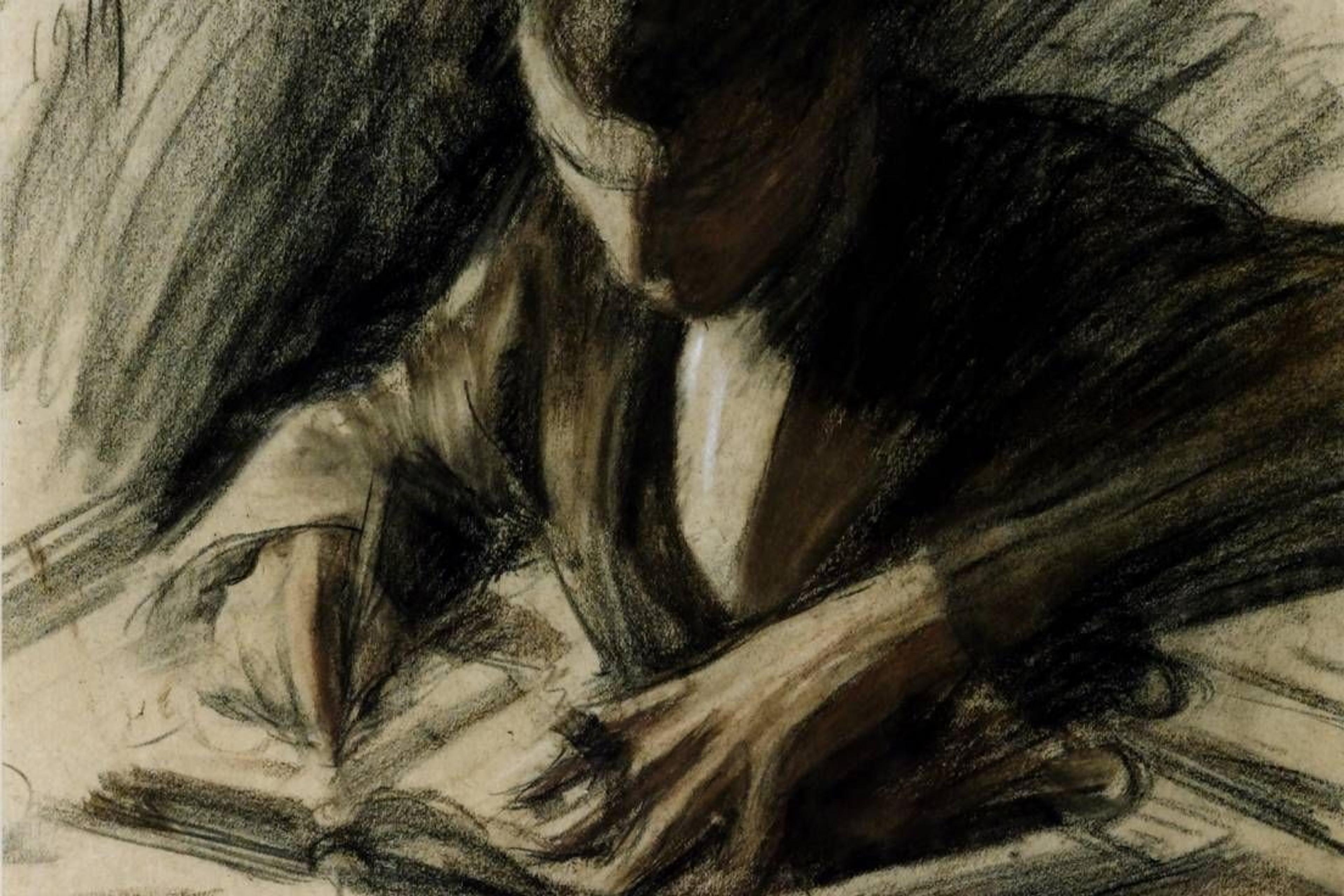

Like many people, like me, Julavits kept a diary when she was young. She grew up believing that in those pages lay the signs of her preternatural talent. But when she returned to the scribbled booklets many decades later, she discovered that mostly her writing was unimaginative, boring. She’d recorded her test scores, the boys she found cute, TV shows she’d watched. Her diary was notable solely because she wrote in it every day.

Recalling the formulation she had used as a child, the entries in The Folded Clock each begin in the today: ‘Today I had a dinner party.’ ‘Today my husband and I cleaned out our storage space.’ ‘Today I swam out to sea with a stranger.’ Julavits gossips with friends, takes the bus, visits antique stores. Hers is a lovely, lucky life, marked by summers in Maine and residencies in Italy and Germany. But it is also a life like every other, in which very rarely do individual moments seem momentous as they happen.

A distrust of an objective reality runs throughout Julavits’s writing. The selves she has conjured over several novels and works of nonfiction mutate and mutiny, sensations that Julavits, too, has perceived in her own body. Indeed, it was after receiving a medical misdiagnosis that she began keeping an adult diary. As she explained to an interviewer:

I don’t want to get too deep or morbid, but I suddenly became aware of my body as an unreliable container. There’s always a great distance between the internal and the external selves, but this distance, when I was in pain, seemed scarily unbridgeable.

Time is the subject of The Folded Clock, but in Julavits’s hands it is made pliable. Her clock is defined by echoes and returns that wrap back upon themselves: 16 November comes after 7 September but before 5 August. While structurally fickle, this is how memory operates: people circle in and out, objects serve minor, then major roles; there are acts and reprises and second chances. The experience of time is hardly ever chronological.

In illness especially, time can take on new forms. ‘It was no longer linear,’ writes Julavits. ‘I did not see time ahead of me. I experienced time on top of me. I experienced time underneath me. Time became a hollow, vertical enclosure.’ She suffered from ‘plummet[s] in time altitude’ in which moments in her life seemed to speed up or recede. Her days became asynchronous.

The Folded Clock was published in 2015, but Julavits’s ‘drops’ could easily describe 2020. Only now, such plummets are more an anaesthetising, interminable ooze than the vertigo that Julavits described. The COVID-19 pandemic has wrung meaning from time. Each day is so like the former. April disappeared entirely; Thanksgiving feels as close, or faraway, as last June. I no longer can keep track of the dates; time has become a pool of standing water.

At this time, what the Greeks termed Kairos, designating the correct or auspicious moment (as opposed to Chronos, which refers to sequential time, or Aion, which denotes the ages or cyclical time) feels very out of reach. Even so, there is no singular clock, no one ‘time organ’, as the psychologist Robert Ornstein put it, to which we all adhere. Instead, our temporal perspectives are cultural (one friend tells me that she sees a year in the shape of a sea cucumber, and a lifetime as vast and unknowable as the ocean floor), and physiological. As neurobiologists have shown, how quickly or how slowly we feel time passing fluctuates wildly for each of us, its pace, according to researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, linked to the formation or lack of new memories and the flow of new experiences. Time is ruled entirely by one’s own sense of being, by hunger and humiliation, by lovesickness and dread and delight. The metrics cannot be severed from the rhythms of a life.

In his novel Austerlitz (2001), W G Sebald’s titular character finds the cultural segmentation of time almost incomprehensible:

And is not human life in many parts of the earth governed to this day less by time than by the weather, and thus by an unquantifiable dimension which disregards linear regularity, does not progress constantly forward but moves in eddies, is marked by episodes of congestion and irruption, recurs in ever-changing form, and evolves in no one knows what direction?

Time, as he sees it, is always in flux. It is as uncontrollable as the wind. For Austerlitz, who allows himself to learn the fate of his family during the Holocaust only as an adult, this awareness is a crippling, debilitating force that bears down upon his body: this temporal vortex is entirely autobiographical, and serves as a reminder of all that he has lost.

During these lockdown cycles, especially in the darkness of winter gloom when evenings stretch on endlessly, I’ve found duration to be incalculable. I read, I put the book down, I pick it up again, I stop. Time lags. Time sags. Politicians repeat their assurances that we will defeat this virus, but a lethargy directs the days, making them melt together. To anchor myself, I reach for things that took place decades and centuries ago. I read about Albert Kahn, the 19th-century French banker who, afraid of losing the world he knew to industrialisation, tried to inventory the whole of humanity. He created an archive of more than 72,000 images in his efforts to stave off a disappearance – a collection that, unsurprisingly, was never completed. Much of what Kahn saw no longer exists, or no longer exists in the way that he saw it, and I imagine him in his last years leafing through the images, bathed in what he believed to be the truth of the world.

‘Today I went to the Grand Central Station Oyster Bar at midday,’ writes Julavits, at the close of her book: ‘I was feeling lost and this bar is like a church.’ Beneath the vaulted ceilings, she sips a restorative drink then wanders down Park Avenue where she spots Le Relais de Venise, a restaurant that summons a memory of a long-ago semester she spent in France. Suddenly, it is 20 years earlier; then just as suddenly, it is 10 months in the future, and she is in Rome with her children.

For Julavits, all time is autobiographical. Like Marcel Proust’s madeleine, one bite of which plunges the narrator back to his childhood, her sense of time seems as much governed by the sun rising and setting as it is by a series of objects. Regularly, Julavits is struck by the transformative potential of certain items: an enamel tap handle, a second-hand necklace, a Rolodex fished out of a trashcan at JFK. She holds on to these until their true purpose is unveiled. Part of her captivation comes from her failure to fully ‘possess’ these objects. Their everydayness renders them magical. Their purpose is simply to endure.

Some things overtly suggest their timeliness – photographs and films being obvious examples. But we put a false faith in such images, believing that they can show us the world as it truly was, when, in fact, the final product is just one translation, and at a remove at that. Perhaps a more useful analogy is the Rolodex, which, like a clock, says Julavits, ‘runs forward and backward. There’s an order but there’s no predetermined point of entry.’ As a result, autobiographical sincerity has many forms. As the literary scholar Paula Backscheider argues in Reflections on Biography (1999): ‘Biography is more interesting today because of the acknowledgement that the portrayal of an individual is not the only possible one.’

Like a lifetime or a story, Julavits’s objects persist; they exist and then eventually become. Until then, she lugs them around, totemically, the things onto which she projects her life. These objects inhabit the present perfect, a reverberation which has yet to be concluded. Their timestamp might be more hidden, but it is no less forceful.

Today it is my birthday, and we are going to the National Gallery in London, which has just reopened. Because of the pandemic, the museum has set out specific pathways through its permanent collection. Scanning the map in the entrance queue, we select route B for the Caravaggios, though that means that I will miss Edouard Vuillard’s La Terrasse at Vasouy, The Lunch with its incandescent whites. I take photographs of gilded frames and of Dutch men sporting ruffs. I could live 100 lives through the painted portraits stored on my phone.

Each birthday acknowledges the revolution of the wheel; who is to say that the year must begin on 1 January? Last year, I went swimming in the Ladies’ Pond, on Hampstead Heath in London, to celebrate, and I will go again later this year too. My new year has begun, but all around me the same one drags slowly on. In Confessions 11:21, Saint Augustine asks: ‘In what space then do we measure time passing?’ But Augustine, I have no idea anymore.