When I was 15, one of my closest friends died unexpectedly. Our physics teacher broke the news to me after I’d sat an exam, having wondered all the way through why my friend wasn’t there doing the same. I still don’t have the words to describe how I felt: it was something approaching shock, distress, disorientation. I didn’t know what to think, much less what to do. I spent many nights awake and many days in a daze.

Fifteen years later, when I was in graduate school, another friend died suddenly, a man I loved very much. I remember checking my phone and finding out, to my dismay, via text message. But while my initial response was much the same as before, there was a palpable difference in how I felt later on. While I was again surprised and saddened, I was much less disoriented than I’d been as a teenager. I could still think, and I could still get things done. It seemed to me that I’d become better at living with loss.

You might think that the reason for this difference is obvious – I was older, and I’d had more experience in coping with death. But raw experience alone isn’t enough: what matters more is whether we learn from experience. And learning from experience, especially an experience as difficult as the death of a loved one, can involve quite a lot. Among other things, it can involve creativity.

This claim might seem surprising. After all, creativity is often associated with the idea of a lone creative genius, an individual who not only excels at what they do, but also transforms the world in the process. Further, even if we don’t limit ourselves to romantic or heroic perspectives on the nature and value of creativity, it’s commonly thought that creativity at least aims at novelty or originality.

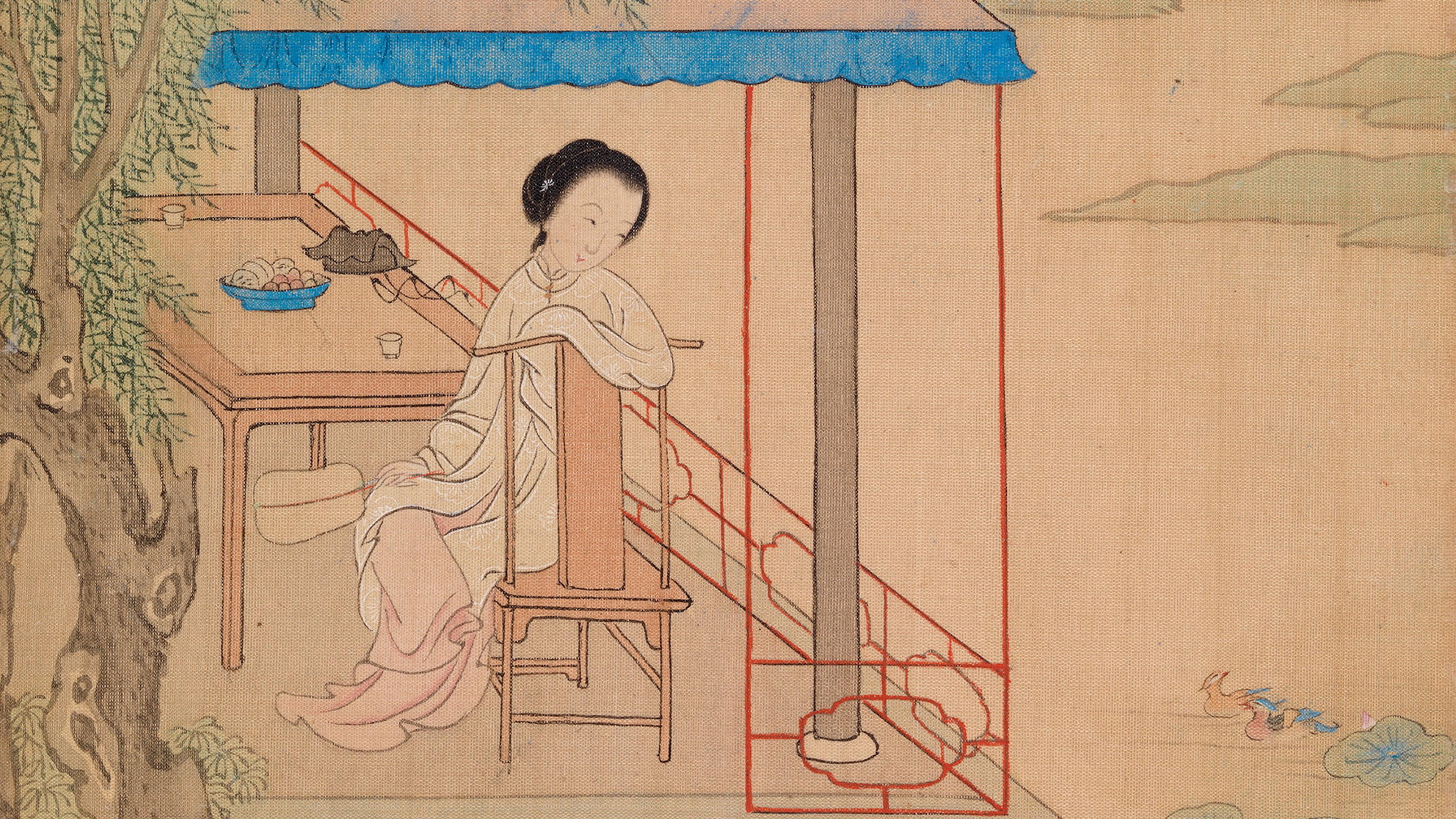

This way of thinking about creativity isn’t universal. The Zhuangzi (莊子), a classical Chinese philosophical and literary text, provides a different perspective. On one interpretation, creativity isn’t conceived as aiming at novelty or originality, but rather integration. Instead of aiming at something new, it aims at something that combines well with the situation of which it’s a part.

The story of Wheelwright Pian, from a chapter of the Zhuangzi known as the Tian Dao (天道), meaning ‘Heaven’s Way’ or ‘The Way of Heaven’, effectively illustrates this perspective on creativity as it pertains to artists or artisans. In this short vignette, a wheelwright known as Pian (扁) tells a duke that the book of sages’ advice he’s reading is nothing but ‘chaff and dregs’. Angered, the duke demands an explanation. The wheelwright responds that, at least concerning his craft, he can create what he does only because he’s developed a ‘knack’ for it that can’t be wholly conveyed in words. If the blows of his mallet are too gentle, his chisel slides and won’t take hold. If they’re too hard, it bites in and won’t budge. ‘Not too gentle, not too hard – you can get it in your hand and feel it in your mind,’ he says. ‘So, I’ve gone along for 70 years and at my age I’m still chiselling wheels. When the men of old died, they took with them the things that couldn’t be handed down. So, what you are reading there must be nothing but the chaff and dregs of the men of old.’

Although he’s a ‘lowly’ craftsperson, the wheelwright has something important to teach the duke. He’s been creating wheels by hand for many years and has developed an ability to act and to execute his craft in an integrated manner that can’t be fully captured through an algorithmic list of instructions. He responds to precise particularities in the wood, his tools and his body to create what he wants – something he doesn’t accomplish by imposing a plan.

The wheelwright is creative not because of his novelty but because of his ability to create wheels in a well-integrated manner

The sages’ advice for living well is therefore mere ‘dregs’ if it’s interpreted as instructions that one can simply read and then complete. Living well in general involves much more than this; namely, a spontaneous integration between contrasting types such as the hard and the soft, as well as the learned and the spontaneous, the active and the passive, and even the unproductive and the productive – all of which apply in the case of carving wheels, as well as elsewhere. In other words, living well involves creativity.

This kind of creativity isn’t taken to aim at novelty or originality as such. The wheelwright is presented as creative not because of anything to do with his, or his projects’, novelty or originality, but instead because of his ability to create wheels in a sensitive, responsive and – crucially – well-integrated manner: one not learned by rote, but rather via engaging in sustained, spontaneous activity.

We can use the story of Wheelwright Pian to better understand why learning to live with loss is a creative pursuit. Although there’s an abundance of books dispensing advice on how to do so, ultimately learning to live with death is a deeply personal endeavour that – like carving wheels – can’t be fully captured through a programmatic set of directions. We must respond to precise particularities of our situation (concerning our thoughts, feelings and overall circumstances) to create what we want to create (such as a sense of peace or closure). This isn’t something that can be accomplished by imposing a plan, even if we make various provisional and highly malleable ‘plans’ on the fly as we go along.

Moreover, in working through our thoughts, feelings and circumstances in all their particularities, it’s not that we’re doing anything all that different from what countless others have had to do as they’ve learned to cope with loss. Nonetheless – again, like carving wheels – it’s plausibly a creative activity, in that it involves a spontaneous integration between contrasting types such as the grieving and the celebratory, the resentful and the grateful, the distressed and the joyous. The ability to live with death, too, in a sensitive, responsive, and well-integrated manner isn’t learned by rote, but rather via engaging in sustained, spontaneous activity. Indeed, even the philosopher Zhuangzi himself can be understood as engaging in such a creative process after the death of his own wife in chapter 18 of the text, the Zhi Le (至樂), meaning ‘Perfect Happiness’ or ‘Perfect Joy’.

This way of thinking about creativity has a variety of other potential benefits. First, even if creativity were taken to aim at originality, de-emphasising originality might ironically result in greater creativity. This is because striving for originality can actually be counterproductive when it comes to achieving genuinely fresh results: if we focus on the task of achieving something original, we’ll explore only the range of possibilities deemed sufficiently likely to yield that result, leaving out a lot that could have contributed to achieving something original.

But imagine instead that we worked with the idea that creativity wasn’t about novelty. That doesn’t mean we’d have to give up the value of originality entirely, but rather see it as one of a range of possible outcomes. Casting a wider net in this way might hence make creativity (whatever it involves) easier to achieve.

Second, focusing on integration could encourage us to better understand creative agents as being intimately connected with, and products of, their environments. This would broaden our notion of creativity in a way that might allow us to see creativity demanded in a greater range of activities. After all, many of life’s activities, from the mundane to the meaningful, aren’t learned by rote, but rather via spontaneous action that integrates contrasting aspects. Just for starters, additional examples might include getting along with one’s family, building relationships with colleagues and organising one’s finances.

This alternative perspective on creativity might help us to see it as an everyday phenomenon in which we all participate – rather than an extraordinary talent or gift that only a few enjoy. And it might also allow us to make sense of the idea of living creatively: of an integrated life, lived spontaneously, in which all of life’s contrasting aspects can be arranged to form a rich and variegated whole.