Think of a recent event that made you really happy – receiving an excellent exam grade, getting a promotion, going on a perfect date. Think back to how you felt in your body before, during and after the most intense moments. Did you feel butterflies in your stomach in anticipation? Did your heart skip a beat or swell with joy? Did you have a spring in your step for the rest of the day?

Emotional experiences frequently co-occur with these sorts of bodily sensations, as reflected in literature, song lyrics and everyday conversations. But have you ever stopped to wonder whether the way you experience emotion in your body is the same as someone raised in a different culture on the other side of the planet, or during a different historical period?

At least some aspects of the way emotions are embodied seem to be universal, suggesting this is a basic part of human biology. For instance, when our colleagues asked people to describe where they felt specific emotions by painting them on a template of a body, the participants displayed a lot of consensus – they tended to agree that pride is felt around the chest, anger in the arms and fists, and so on. In fact, by using the participants’ responses to create bodily heat maps of emotional feeling, the researchers were able to look at a map and differentiate between the six basic emotions (happiness, anger, fear etc) and even different types of love, such as the love you feel for your romantic partner, your parents, or your country.

A study using a similar approach, but involving thousands of people from 101 countries around the world, also showed great consistency in people’s responses, suggesting that the pattern of bodily sensations triggered by emotions is similar across cultures. These findings imply that there is a shared biological mechanism underlying the bodily sensations we describe while experiencing emotions.

This makes intuitive sense. Our emotions ultimately emerge from the brain and body, so it follows that the feelings they provoke are a fundamental feature of human biology. But that’s not necessarily the whole story.

Another important factor might be that bodily sensations are affected by culture and language. For instance, in English, people easy to anger are called ‘hot-headed’, and the connection between heat and anger has been seen across different cultures. But this does not necessarily mean that when study participants’ temperatures are taken there would be a noticeable rise in body temperature preceding aggression. Temperature data in humans in aggressive situations is hard to come by, but, in pheasants at least, aggression is actually preceded by a drop in head temperatures. It is sometimes difficult to separate the true bodily sensations experienced during emotions from the cultural tropes that we’ve learned to associate with those emotions.

It is intriguing to ponder whether the different ways emotions are discussed by different cultures and languages could shape people’s bodily experiences of emotions. Yet, in the current times of worldwide intercultural interactions, often disproportionately influenced by the English language, it is challenging to find truly independent populations because many idioms have spread across multiple modern languages. For this reason, we and our colleagues took a radical approach – we turned our attention to ancient times.

Tablet from the Epic of Gilgamesh describing a great flood, the British Museum. Courtesy Wikipedia

We started with a specific period in Mesopotamian history – the Neo-Assyrian period, which was characterised by a rapid expansion of territory controlled by Assyrians in the north of what is now modern-day Iraq in c934-612 BCE. At its height, the Assyrians controlled territory from the Zagros mountains to Egypt and southeastern Turkey. Of course, we can’t ask the dead of ancient cultures how they experienced happiness or love in their body, but this huge empire left behind thousands of texts in the Akkadian language in various genres – and, for us, this is a treasure trove of data.

Written in cuneiform, a writing system of wedge-shaped imprints, the texts were inscribed on all sorts of objects, but many were clay tablets. Thousands of these texts have survived to this day, been translated by a handful of dedicated scholars, and then published online. This provides perhaps the broadest digitally searchable set of texts from the ancient times, making it a great starting point in our quest to understand how much the bodily expression of emotions may be affected by language, culture and time period.

The study of emotions in Akkadian texts, and specifically the topic of the embodiment of emotions, is a new, emerging field. Most of the work so far has used qualitative and philological methods, requiring a lot of manual labour by scholars spending hours reading and translating hundreds of Akkadian texts. These early studies have revealed frequent references to body-related processes of emotional experiences, including how Akkadian considers internal organs as containers of emotions or embodied feelings. For example, the terms libbu (broadly, the ‘inside of the body’ or ‘torso’, but it can also refer to the belly, the heart, or the womb) and kabattu (‘liver; innards’) are found frequently in descriptions of embodied feelings and emotion expressions. For a specific example, sorrow is sometimes literally referred to as ‘illness of the heart’ (muruṣ libbi).

This initial work suggested the locations of embodied emotions in Akkadian texts is broadly similar to the way many people describe their emotions today. But this isn’t a definitive finding. Our understanding of culturally specific metaphors in Akkadian texts is still in its infancy. And technological developments are throwing up new insights.

Recently, digital editions of Akkadian texts have become available, which has allowed an explosion of research using computational tools. Methods to help understand the broad cultural associations of words in Akkadian have been particularly useful – especially co-occurrence statistics and vector space analysis. These tools can be used to explore complex topics, such as the cultural associations of words or groups of words and emotional expressions. The great benefit has been the ability to look at hundreds of words and analyse across many different categories (such as categories of emotions), all at the same time.

In our work, we studied the co-occurrences of nearly 300 Akkadian words for emotions and more than 60 Akkadian words for parts of the body. We mapped these statistics to a set of three-dimensional models of body parts using a method called word embeddings. These embeddings represent each word as a point in space – if words appear together more frequently, then they will be located closer together. We then used these emotion-body word pairings to create coloured body maps, to show which body parts are mentioned most often in different emotional situations.

Through these analyses, we found that, in the Akkadian language, specific body parts (such as the internal organs) are consistently highlighted in the body maps of 18 different emotions. Next, we compared the maps for the 18 emotions statistically and we uncovered four discrete patterns or clusters of bodily sensation, each reflecting a different emotional category or group of emotions.

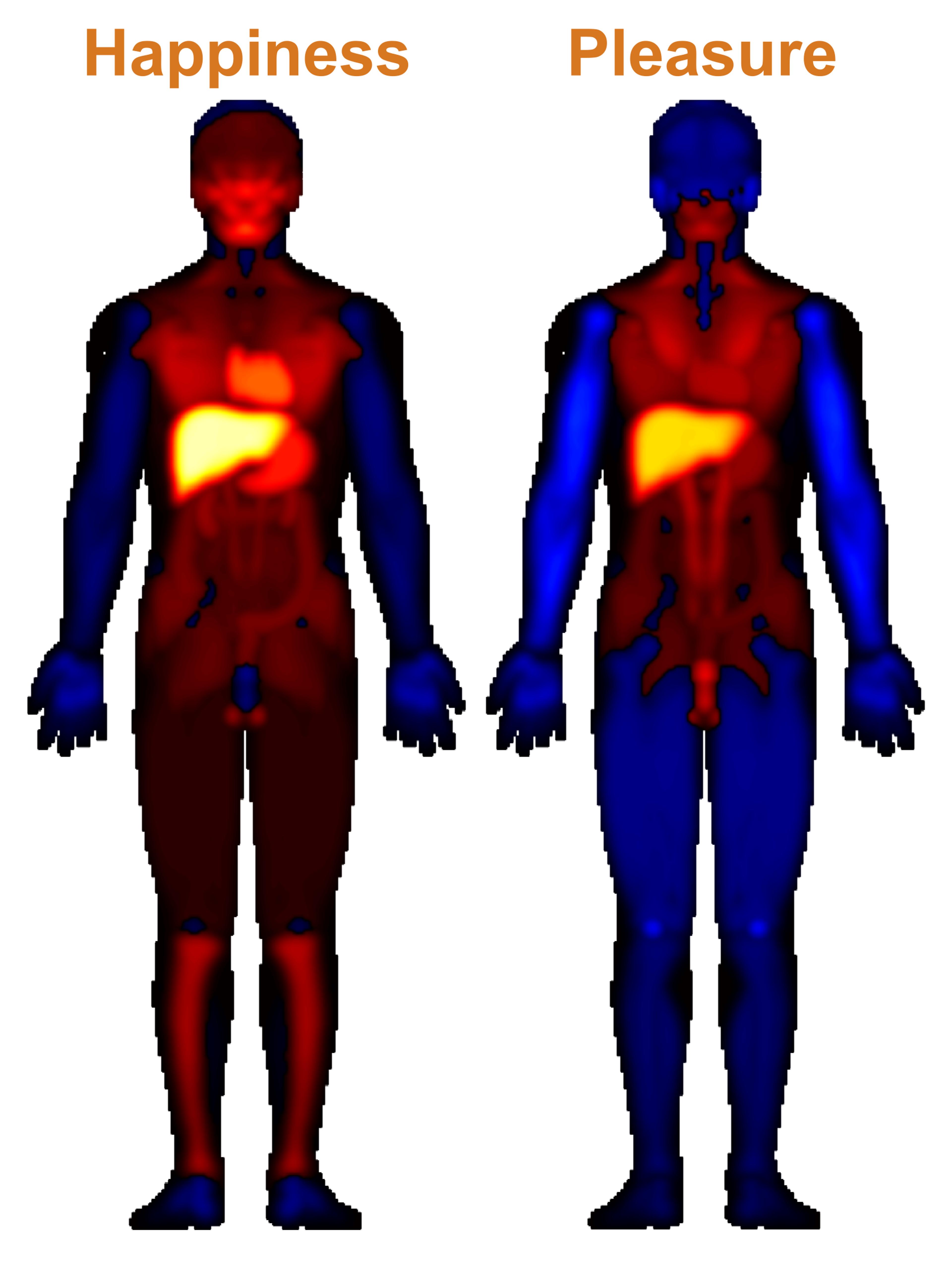

Of these groups of emotion words, the cluster for ‘happiness’ and ‘pleasure’ was the most consistent and visually striking: the liver burning bright, surrounded by a dimmer glow around the heart and stomach, and radiating its warmth across the chest, the face and the abdomen. The importance of the liver as the seat of happiness was seen across several of the words describing happiness. This result fits well with findings from the earlier philological research. Indeed, the idiom kabattu (‘liver’) plus neperdu (‘to be bright’) means ‘to be happy’, matching our interpretation of the body maps.

This bright focus on the liver as the seat of happiness, although well known in the ancient texts, is very different from the way that people describe their bodily experience of happiness today. When reflecting on the physical feeling of happiness, our modern-day participants instead pointed to the heart, stomach chest and face. Not a liver in sight! Clearly, the way we discuss emotions in our body has changed since the Neo-Assyrian Akkadian texts.

Importantly, in the Neo-Assyrian period, the liver and heart were not only relevant in the context of happiness, but were also mentioned frequently alongside a broad range of other emotions, ranging from love to anger. This is consistent with the liver being considered the seat of the soul in many ancient cultures due to its striking appearance in the body, as seen for example during animal sacrifice. It has also been used in different emotional contexts in several languages. In modern times, the heart is still mentioned together with several emotions, but the liver has since largely lost its emotional connotations, at least in the English language. For us researchers of emotions, this provides a striking reminder that we need to take cultural specifics into account when looking at how people experienced emotions.

Knees were one of the body parts most often mentioned together with words expressing love

Setting aside the liver, there are many similarities between modern descriptions of happiness in the body and the Neo-Assyrian experience – the heart, stomach, chest and face were highlighted in both cases. On some level, then, there is also cross-cultural similarity regarding where human beings feel happiness, even if they’re separated by nearly 3,000 years.

But these were results for just one of the main emotion categories out of four. When we drilled down into the details of how the hundreds of emotion- and body-related words clustered together, we observed some surprising associations. For instance, in our analyses, knees were one of the body parts most often mentioned together with words expressing love, which has not yet been reported based on philological studies. Certain song lyrics from modern times come immediately to mind from this word pairing (like ‘Falling in Love is Hard on the Knees’ by Aerosmith), but to understand the association in Akkadian, we must study the ancient texts more closely.

Several other open questions remain. On top of our list, how has the way we discuss emotions and the body changed over other time periods, languages and cultures? And which aspects of the differences we already observed between ancient and modern body maps are due to the different methodologies – asking people versus analysing texts – and how much is due to genuine differences in the experience of emotion?

We believe our methods can enable comparison of emotional experiences across different languages, periods and cultures. But to make sure, we will apply our computational analysis of text to cover modern English and Finnish as well as Akkadian, to explore how much the embodiment of emotions differs across these three languages and cultures in literature, how similar they are to the self-reported bodily feelings, and what might be responsible for the differences.

What does this all mean for the bodily sensations you experienced during that happy time we asked you to imagine earlier? It means the experience of happy emotions might not be as universal as is often assumed. Just think: if you lived in the ancient Near East, perhaps rather than your heart swelling with joy, your liver would have been flaming with delight instead.