If given the option to choose between fear and bravery, pretty much everyone would choose to be brave. The history of moral philosophy agrees. Aristotle’s positioning of courage as a key virtue set the stage for the Western philosophical distaste for fear. Add to this common messages about fear – that ‘the only thing we have to fear is fear itself’, that we live in a culture of fearing the wrong things, that moments of widespread fear are often seized on for Right-wing political gains – and it is easy to see why fear is seen as something best avoided or overcome. The real moral goal is bravery.

Identifying fear as inimical to effective social and political action makes fearers out to be not only unfortunate in their suffering but morally deficient. Nelson Mandela, a moral exemplar if there ever was one, said: ‘May your choices reflect your hopes, not your fears.’ When fears are failures according to persuasive social, political or ethical narratives, individuals have all the more reason to avoid them.

Yet many of our greatest threats – mortality, suffering and loss – are impossible to outrun. Living means confronting these fears. They cannot be ducked or dodged. In the face of such facts, should we accept nothing less from ourselves than bravery? Are we really morally deficient if we meet the prospect of our own death with anything but courage? What if we instead conceived of fearing not as the morally worse alternative to bravery, but as something we could actually do well?

Suppose your greatest fears are going nowhere. They will be constant companions, even as your circumstances change, and you grow older and (potentially) wiser. Consider a number of options for how you might comport yourself towards these fears, besides running away from them towards bravery. One option is acceptance. You relate to your fears with a tranquillity born of detachment. You accept the fears you cannot change and go about your life. If acceptance seems too great a lift, consider something more resigned: living with them. Like disrespectful neighbours who will never relocate, we might tolerate, co-exist with, or even abide by these fears.

Living with fears without trying to avoid them may be one part of fearing well, and one for which a culture of fear-as-failure has not prepared us. Living with fears is, further, something we do by living with fearers.

Moving away from a dominant picture of fearing as a private endeavour, we can begin to see that we arrive at the fears we have in the context of the fearing of many others. Both by attachment relations early in life and in ongoing fear acquisition, we come to fear what we fear together. Further, we can see that processes of fear formation depend on ongoing interpersonal expression and uptake. If we feel something like fear but the people around us deny or dismiss our attempts to express that feeling, we can actually be prevented from having the feeling in the same way. We may never be able to identify what we are feeling or what the feeling is responding to. The people around us are that important to the feelings we have. Their responses can actually make it possible (or difficult) to have and understand our own fears.

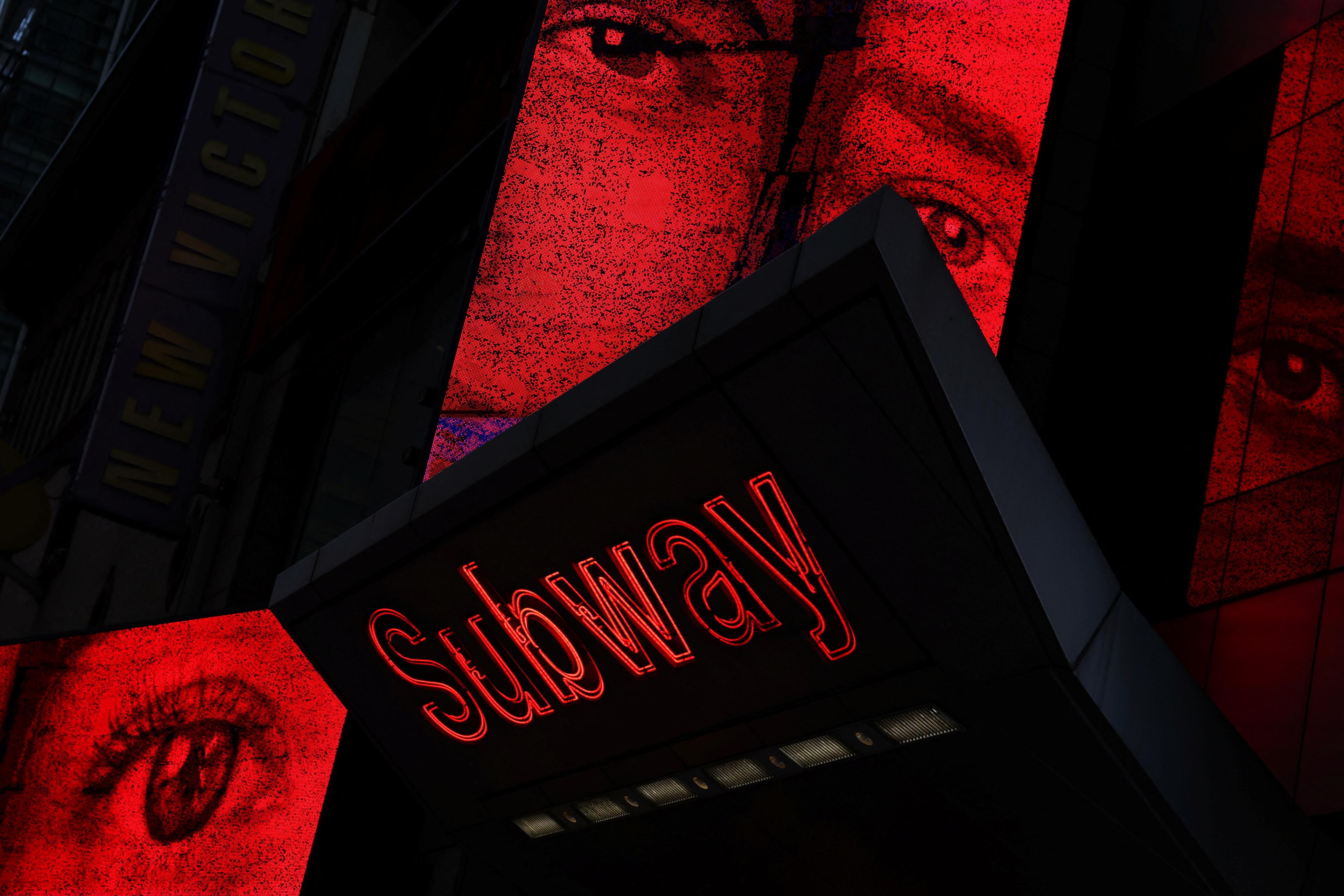

One kind of negative reaction we sometimes find ourselves giving or receiving is brave-washing

If we care about fearing well, and if fearing well means, in part, living with rather than avoiding our fears, then we need to build and participate in relationships within which we and others have fears without rushing to avoid them. Such relationships will be ones that allow us to experience and express fears, verbally or otherwise, without negative reactions.

Given our widespread predilection for bravery, it is unsurprising that one kind of negative reaction we sometimes find ourselves giving or receiving is what we might call brave-washing: a refusal to believe that some fearer is anything but courageous. Sarah Wildman has written a series of pieces for The New York Times about her daughter Orli’s diagnosis of liver cancer at only 10 years old and the years of treatment that followed:

In these years as cancer caregivers, we have often been told how brave we all are. I always find the sentiment lovely but misplaced. Bravery implies some agency in the matter. And what choice do we have? We have spent the last 38 months putting one foot in front of the other.

To suggest that such a parent is brave, or that they could or should overcome their fears and replace them with hope or another more palatable feeling, is a kind of dismissal. The parent can and should have all their fears. Individuals and families facing health crises might (with certain supports) also be able to remain connected to what Wildman describes as expansiveness – the space to take a slightly deeper breath between emergencies and treatments – even while the fears run right along beside them, and even if the worst outcomes ultimately come to pass.

When expressions of fear are regularly met with dismissal, judgment, blame or shame, fearers learn that their fears are not tolerable and perhaps better avoided altogether. By contrast, when expressions of fear are met with sympathetic uptake, fearers learn that their fears can be tolerated and that they won’t be left alone to figure out how.

Unlike images of meditating individuals floating ever further from others and deeper into their private experience, recent research on mindfulness suggests that mindfulness is actually about relationality, and made possible by foundational relationships with others. Being afraid is hyperarousing. The physical and verbal responses of others can make it more possible for us to sit with and observe experiences of fear rather than rushing away from them. Somatic regulation approaches, too, note the significance of relationships in making fears bearable. Feeling grounded and secured by physical contact with others – being held, embraced or rocked – can allow individuals to bear fears as feelings that will not last forever. Feeling heard and recognised in the verbal expression of one’s fears allows for regulation of the limbic system.

The actual responses particular fearers experience as most sympathetic will vary based on personality and history. Whether being able to talk about fears, hearing from others about similar fears, or just having others remain physically present, still or in motion, the ways one friend feels best supported with fearing may differ from the ways another does.

In moments of great fear, as in moments of other difficulty, there are concrete things we can do for each other: offering food, company or acts of faith. While living with fearers can be some of the most quotidian care work we provide and accept, it can also be some of the most wrenching. As Wildman wrote after her daughter’s death: ‘Orli wasn’t fearless. She engaged with fear: She spoke to it, got under it, wanted to understand it, didn’t run from it. She insisted that we, her parents, sit with it and not lie to her about it.’

Fear is made more tolerable when we are neither left alone with it, nor positioned as failures for experiencing it. Whether we manage to embody morally acceptable responses to the fears we inevitably have depends in large part on what is made possible within our social worlds. If we want better responses to fear – including responses that do not lash out at non-threats in an attempt to calm ourselves down – we need to build relationships that will better support fearers. This can mean something as simple as not leaving others alone with their fears. Doing so is an act of connection but also of fearing well. Such fearing is not only not inferior to bravery, but perhaps the more important, and more challenging, goal.