Over the past decade or so, there has been a huge shift in our attitude to sleep in the Western world. We’ve moved from ‘I’ll sleep when I’m dead’, ‘Sleep is for wimps’ and ‘Money never sleeps’ to scientists, doctors and health bloggers alike emphasising the huge importance of getting our Zzzs.

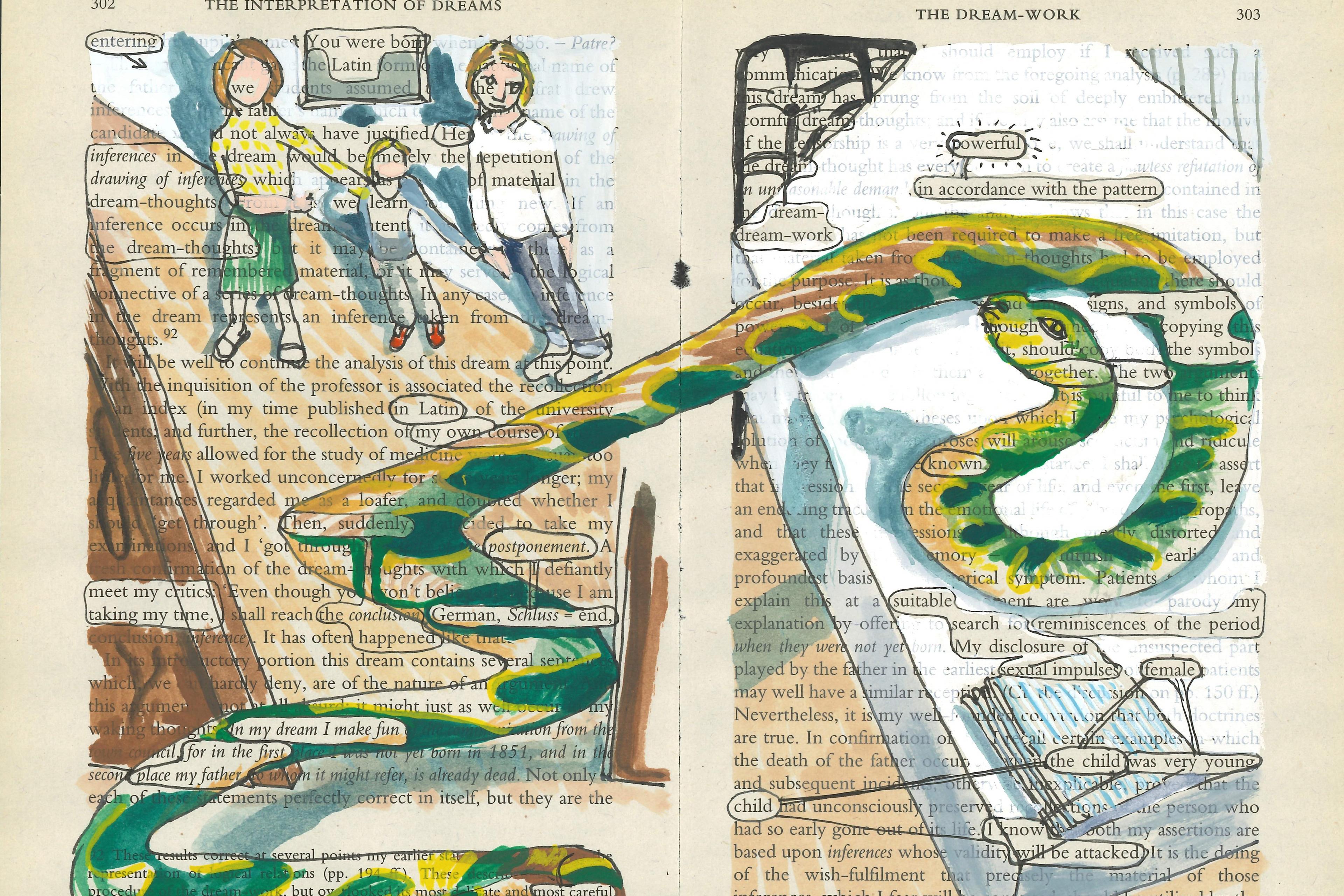

It’s positive that people now take sleep more seriously but, as a sleep researcher myself, I fear things have gone too far. Increasingly, many people, who by any objective measure are getting enough sleep, are worrying unnecessarily that their sleep is not ‘good enough’. In 2017, a group of US sleep experts coined the term ‘orthosomnia’ to refer to a desire for ‘perfect sleep’. They described how people are now arriving at clinics clutching a sleep tracker or a popular science book, explaining that they had always considered themselves to be good sleepers until…

Another unexpected consequence of so much promotion about the importance of sleep is that people who, for reasons outside of their control, are struggling to get enough sleep are becoming increasingly distressed about it. This applies to many people in society but, as one example, consider those who care for others with disabilities that require around-the-clock monitoring or support, and who therefore miss out on what my colleagues and I call ‘sleep privilege’ – the luxury, enjoyed by some, to sleep under optimal circumstances and conditions.

Yes, sleep is undoubtedly important, but dramatic headlines stating it is the most important factor for health, or that too little sleep can be devastating, are typically unwarranted, and it seems that its value might be beginning to be overinflated. Looking ahead, could it be that some of the challenges caused by undervaluing sleep will be replaced by those linked to overvaluing it?