‘Your answers on this questionnaire suggest moderate to severe depression,’ I said gently. ‘Can I ask how long that’s been going on?’

My client, a middle-aged, widowed military veteran with chronic back pain, looked taken aback. ‘Depression?’ he repeated, in a voice of disbelief. ‘No, that can’t be right. I can’t be depressed.’

‘I’m sorry,’ I said, puzzled, ‘but what do you mean you can’t be depressed?’

‘Well, depression…’ he mumbled, ‘it means you’re unreliable. It means I might be a danger to myself or others. It means I can’t volunteer at the animal shelter anymore because I might hurt the animals.’

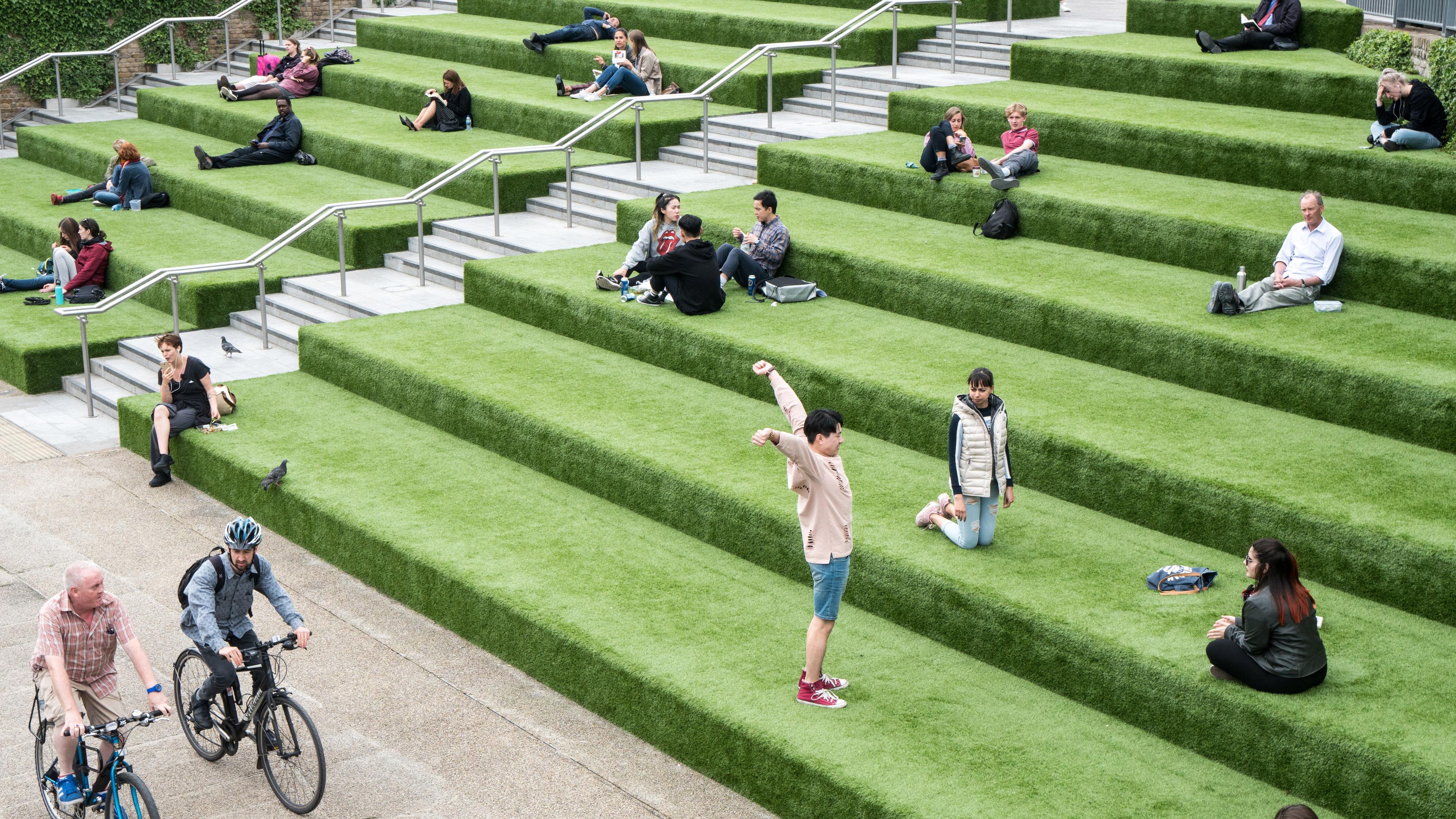

‘Whoa!’ I said quickly. ‘That is very much not what that means.’ I put down his intake questionnaire and gestured vaguely out the clinic window. ‘Do you know how many people out there will develop depression?’

The proportion of the population who have experienced a psychiatric disorder, such as ‘major depression’, at some point in their lives is what epidemiologists refer to as ‘lifetime prevalence’. This statistic has a range of important practical implications. For example, higher rates of a disorder might suggest that correspondingly greater resources should be allocated to support early diagnosis and treatment. Evidence that disorders are relatively common might also provide some comfort to those afflicted, helping to reduce stigma. Given that many common mental health problems can be brought on or exacerbated by structural problems in society, data showing a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders might even encourage us to take a closer look at the major sources of stress in modern life, such as income inequality, systemic racism or exposure to violence. Finally, evidence for high prevalence could challenge some of our assumptions about the nature of mental health – including, for example, that a life free from mental disorder is ‘the default’, and any life that falls short of this standard is an unfortunate aberration.

Given these implications, it might come as a surprise that prevalence statistics in psychiatry have only recently begun to approximate ‘settled science’. A key reason is that, for most of the 20th century, psychiatric disorders were too nebulous to be diagnosed reliably by lay interviewers in large, community surveys. One way of circumventing this problem was to look at the proportion of individuals diagnosed by trained professionals in treatment settings but, because most people with a diagnosable mental health problem don’t seek or receive treatment, the number of clients treated for mental health problems in healthcare systems will almost always be far lower than the number of people struggling with these issues in the general population.

Eventually, however, the diagnostic criteria and interviews used in psychiatry improved to the point that diagnoses could be made reliably by lay interviewers. These advancements laid the foundation for the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS). Conducted in the early 1990s, the NCS was the first large-scale study in the US to assess the prevalence of mental disorders in a nationally representative, community sample. Based on interviews with more than 8,000 adult participants, the survey revealed that close to one in three of them had met criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis in the past 12 months, and that nearly half had experienced a diagnosable psychiatric disorder at some point in their lives.

Early reactions to the NCS were mixed, with some interpreting the findings as evidence of a hidden ‘epidemic’ of mental illness and others arguing that the high rates of disorder in this and other studies simply provided more evidence that psychiatry was ‘medicalis[ing] normality’. Against this contentious backdrop, newer longitudinal studies that followed research participants for decades began drawing attention to a new statistical wrinkle: ‘recall failure’.

Recall failure is a catch-all term used in epidemiology to describe discrepancies between what a person reports at one time point versus another. For example, if you follow the same people for three decades and ask them every few years if they’ve ever had diabetes, research shows that the number of people who say ‘yes’ at some point during this 30-year period will generally be the same as the number who say ‘yes’ when you ask them again at the very end of the study. Thus, diabetes is a condition with minimal recall failure because people who have diabetes hardly ever forget it.

By contrast, longitudinal studies of psychiatric disorders find that these conditions register as more than twice as common when people are assessed for them repeatedly versus when they are assessed at a single time point and asked to look back over their lives – a sign of high recall failure. The reasons for the high rates of recall failure in psychiatry are likely complex and multifaceted, but chief among them are that most episodes of mental disorder are temporary, and people (especially those who never seek treatment) will often forget about or re-frame their mental health struggles once they come out on the other side feeling better.

In the same year that I found myself talking to that military veteran about what it means to be depressed, I was investigating the issue of mental health prevalence with my colleagues at Duke University in North Carolina. To get an up-to-date, big picture of the issue, we wrote a report summarising results from some of the most recent epidemiological studies of mental disorder conducted all over the world. To minimise the distorting effect of recall bias, we placed particular emphasis on longitudinal, decades-long studies of community samples. In the longest-running studies with the most frequently assessed samples, we found lifetime prevalence rates of psychiatric disorder either approached or exceeded 80 per cent. This was a striking result because it suggested that, statistically speaking, not only is an episode of diagnosable mental disorder common, it’s normal. And although critics of psychiatry might view a statement like that as yet another attempt to ‘pathologise the human experience’, another perspective is that science is simply confirming that mental health problems are actually a lot like physical health problems – common, often temporary and, for most of us, an unavoidable consequence of the wear and tear of ‘normal’ life.

For perhaps the first time in psychiatry’s relatively short history, we’re uncovering rates of mental disorder suggesting that all of us – researchers, clinicians and lay people – might need to rethink what it means to be mentally well. And there’s another important angle to this line of research. If living a ‘normal’ life means having at least one episode of a diagnosable mental health problem, what do we call the small minority of people who never seem to develop these problems? Perhaps even more exciting, what might we learn from them?

My colleagues and I decided to take a closer look at the mental health ‘superstars’ in our data who enjoy what we called ‘enduring mental health’. This group is interesting to researchers in psychiatry like me for many of the same reasons that gerontologists (scientists who study the ageing process) are interested in centenarians. In short, it’s possible that, by studying the biology, psychology and environments of these unusual individuals, we might eventually uncover the secrets to their apparent mental and emotional resilience. One finding that surprised us is that people with enduring mental health aren’t necessarily born into extraordinary privilege. The socioeconomic standing of one’s parents might guard against some of the worst forms of certain mental health problems, but seems to have little to no bearing on one’s likelihood of making it through life with no diagnosable psychiatric conditions whatsoever. What seems to matter more is the mental health history of your parents, in that people who never develop a diagnosable mental health problem tend to come from family backgrounds where these conditions are also comparatively rare. This suggests that people with enduring mental health might benefit from protective genes (or even subtle differences in parenting practices passed down through the generations) that promote healthy adaptation in the face of adversity.

While the relationships between enduring mental health and these family characteristics are thought-provoking, the most practically significant findings from people with enduring mental health concern the individual attributes that we might be able to change. For example, people who never develop a diagnosable mental health problem tend to be less emotional, more social and display better self-control as children than people with more ‘typical’ mental health histories. This finding aligns with research indicating that most psychiatric disorders occur disproportionately in people with personalities characterised by high neuroticism, low agreeableness and low conscientiousness (meaning that they tend to experience strong negative emotions, are difficult to get along with, and struggle with self-discipline and organisation). Although personality traits have traditionally been thought of as relatively ‘fixed’ patterns of behaviour, a new but growing stream of research suggests that our personalities can actually be significantly and enduringly shaped by experiences that include psychotherapy, psychiatric medication and non-clinical interventions such as mindfulness training and aerobic exercise programmes. In time, my own and other people’s research that examines the genes, brains and bodies of people with enduring mental health might hopefully uncover additional treatment targets.

That said, right now I believe that the most important part of this story is not the predictors of enduring mental health – it’s the prevalence. Science is just beginning to identify the temperamental, environmental and lifestyle factors associated with a life lived free from mental disorder, and the practical benefits of this kind of research are likely still several years away. On the other hand, research documenting the rarity of enduring mental health (and the ‘normality’ of mental health problems) has been accumulating for decades. And yet, for too many people – like the veteran I spoke to about depression – the process of coming to terms with and seeking treatment for a psychiatric disorder is fraught with unnecessary and unwarranted feelings of inferiority, alienation and shame. This disconnect between the perception and reality of mental illness is counterproductive and needs to stop. I realise this goal won’t be achieved entirely through educating more people about mental health statistics, but I still believe it’s a good place to start.