Four feet tall and made of bronze, Kristen Visbal’s Fearless Girl stares down the New York Stock Exchange with a determined expression (the statue was originally installed across from Arturo Di Modica’s Charging Bull in New York’s financial district). Its subject’s scrappy defiance expresses the ideal embedded in its title: fearlessness. We praise athletes or activists as ‘fearless’; ad campaigns and T-shirts encourage us to ‘be fearless’. We admire fearlessness not for its own sake, but because we associate it with the virtue of courage. Courageous people seem to be distinctively uninhibited by fear while pursuing worthwhile goals. The American author Ralph Waldo Emerson expressed this intuition when he called courage ‘the perfect will, which no terrors can shake’.

But one might object that what makes bravery so admirable is not fearlessness but rather the brave person’s ability to act despite their fears. We praise firefighters who risk their lives to save someone as ‘courageous’, it seems, not because they are unmoved by terrifying danger, but because they feel afraid and nevertheless press on. So there is a question: is courage a matter of being fearless, or of feeling fear in the right way?

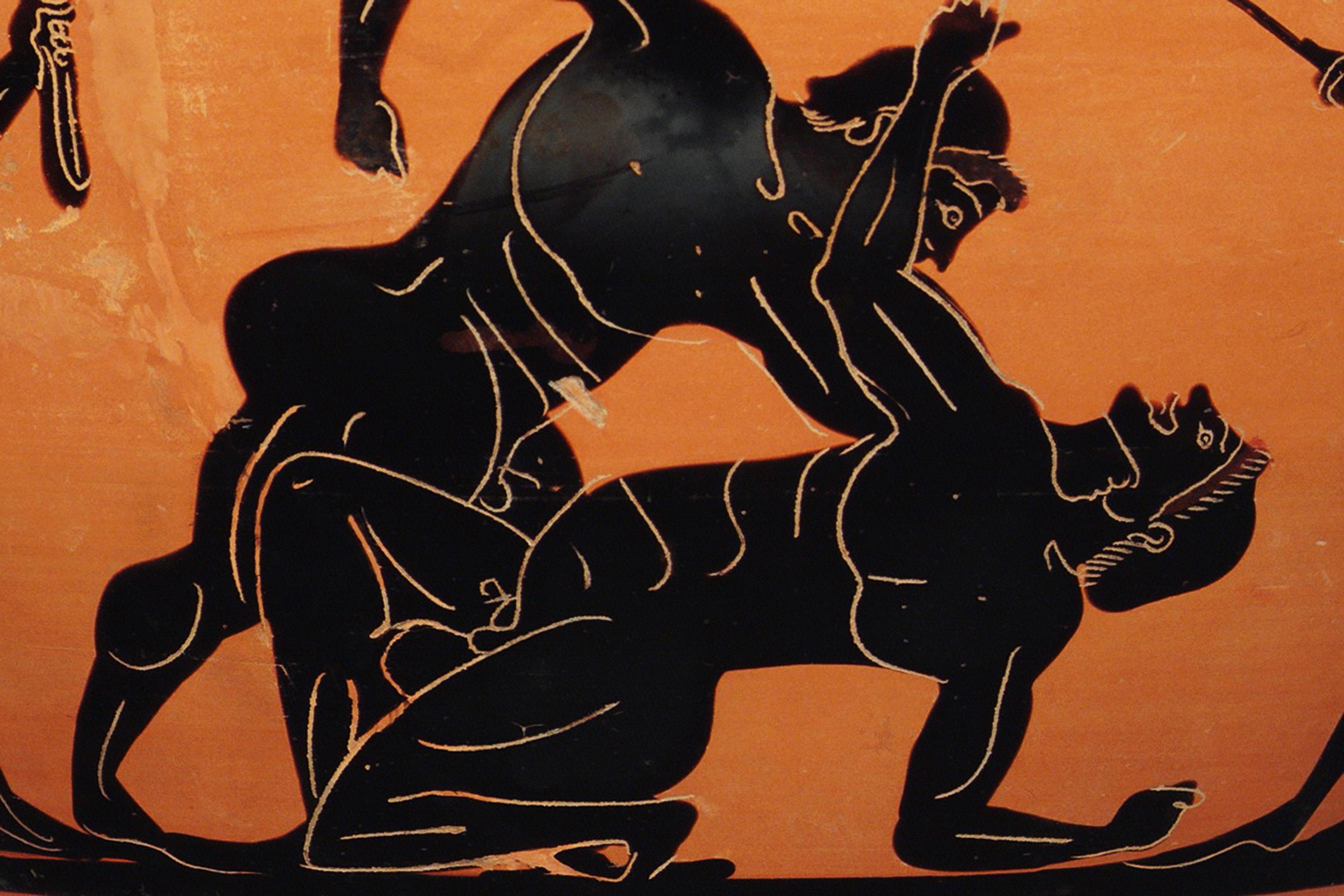

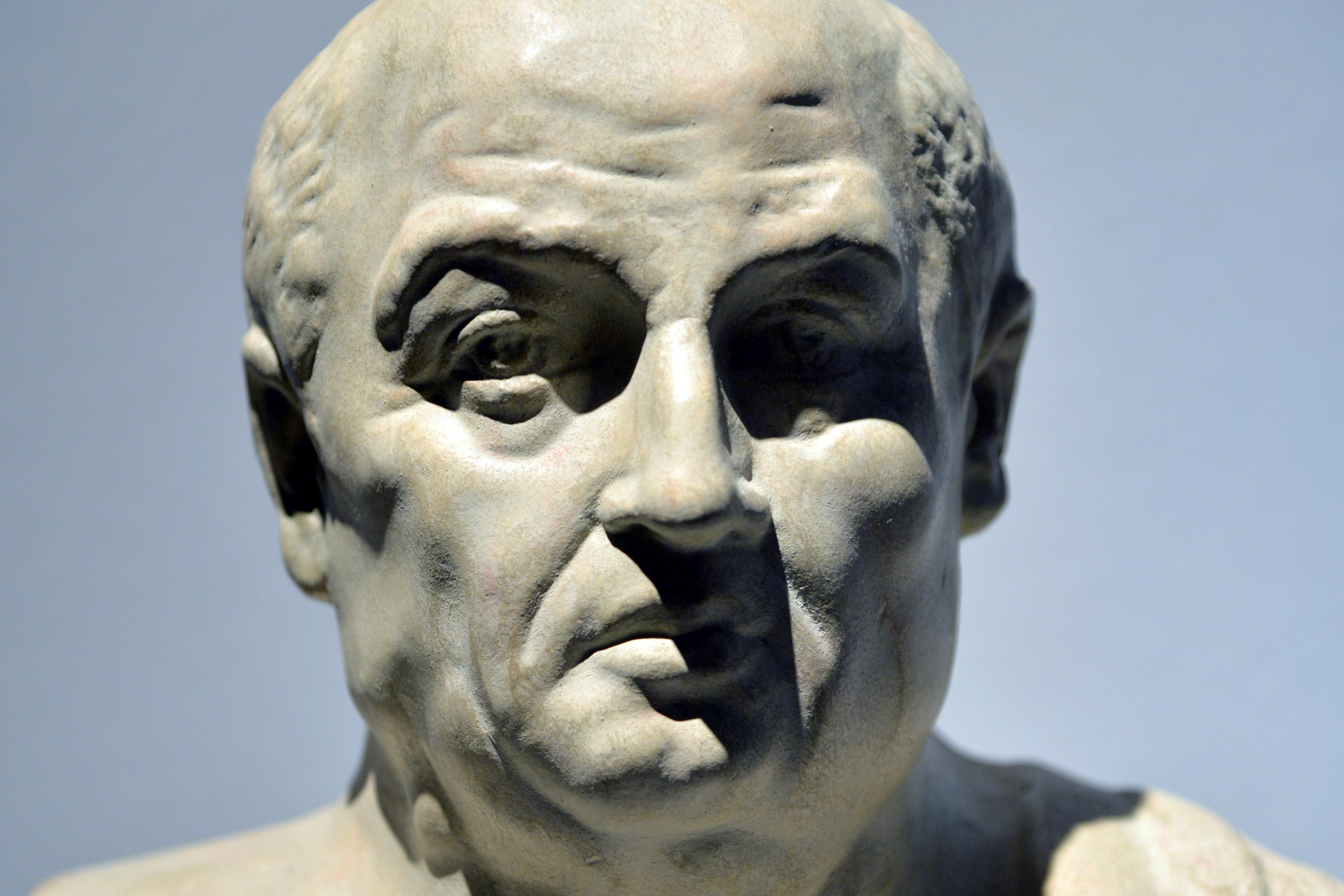

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle encountered this puzzle while investigating the virtue of courage. In the Eudemian Ethics, he first considers the brave person to be ‘fearless’ (aphobos). But, in the next breath, he considers a contrasting view: if brave people face things that frighten others, but that they themselves do not find frightening, then ‘one would say that there is nothing worthy of respect in that’. To understand how Aristotle navigated between these two answers, we should examine his theory of virtue and feeling.

In the Nicomachean Ethics, his better-known work on the good life, Aristotle explains that the ethical virtues are good states of character, acquired by habit, that dispose us to feel and to act in an excellent way across the various emotions and activities that texture our lives. Whether blood-boiling anger or the inviting pull of sensuous pleasure, ethical virtues enable us to have appropriate feelings for a given context: to feel them to the appropriate degree, at the proper time, in relation to the right objects and people, for the right reasons, and in the right way. This may strike us as odd if we think that emotions are natural events, like storms rippling through us. On that view, there is no right or wrong way to feel emotions since we have no control over them. Aristotle, however, thinks that we can learn how to feel emotions in the right way through habituation and practice.

The courageous person has something to lose. But they have something to gain, too

Take Aristotle’s virtue of courage, which regulates feelings of fear and confidence. Like all ethical virtues, it is an intermediate condition between two extremes of excess and deficiency. The courageous person is intermediate between a coward, who is overly fearful (and deficiently confident), and a rash person, who is excessively confident. Unlike a coward, who may go to the extreme of fearfulness (by feeling too much fear, or fearing the wrong sorts of things, and so on), a courageous person is uniquely disposed to feel fear in the right way (that is, by fearing the right things, at the right time, in the right degree, and for the right reason).

Aristotle does not think that one exhibits courage by facing up to any frightening thing, nor cowardice by fearing many things. (He says it would be wrong not to fear some things, such as disgrace). Aristotelian courage concerns a particular object of fear, and brave people judge a specific kind of terror to be worth facing: namely, the fear of death or serious, painful wounds. And not just any death – the consummately brave action is to stand firm in the face of a noble death, as manifested especially in war.

His emphasis on a noble death may have an ancient ring to modern ears, but his account helps to draw out one of the distinguishing features of courage (and of virtue in general): namely, the virtuous person’s motivations. Virtuous people act for the sake of what Aristotle calls the kalon: the ‘noble’, the ‘fine’ or the ‘beautiful’. Brave people may be fearless at sea or in disease – and that may be admirable – but they do not exhibit courage unless they perform an action because it is noble to do so, rather than (for example) because it is only useful.

Aristotelian courage, then, is something much more specific than merely controlling our fears in the face of life-threatening danger. A soldier who stands firm in battle out of fear of corporal punishment or dishonour is not truly courageous; the truly courageous person, in contrast, stands firm in battle precisely because it is noble to do so in that moment. The courageous person has something to lose (their happy, virtuous life). But they have something to gain, too: the achievement of a kalon action. We can extend this account and think of modern examples for something akin to Aristotle’s distinctive conception of bravery: a political activist protesting for civil rights in the face of entrenched oppression, despite the risk to her freedom, because it is the right thing to do; firefighters rushing into a burning building to save someone’s life, at risk to their own, because it is the right course of action.

So, does courage involve being fearless or handling fear well? In the Eudemian Ethics, Aristotle says that the brave person is ‘fearless’ concerning what is unconditionally frightening, and although the courageous may fear things ‘slightly’ or ‘infrequently’ – and great danger only – his point seems to be that they feel little to no fear when acting courageously. In the Nicomachean Ethics, he says that a brave person is a ‘fearless’ type (aphobos) and that they are fearless (adeēs) in the face of a noble death. Perhaps the appropriate amount of fear is none at all.

If this were Aristotle’s view, however, it would be hard to square his claim that some are fearless in excess. Fortunately, his account is nuanced enough to include courageous fear. In the Eudemian Ethics, he likens courage to strength: just as a strong athlete can be worn out by vigorous exercise but is unaffected by what wears out the average person, so too brave people can fear extreme terrors, even though they would not bat an eye at the manifestation of an average person’s fears. Brave people are especially resilient when it comes to fear, but are not entirely unaffected by it.

Although brave people are as ‘undaunted’ as a human can be, Aristotle says in the Nicomachean Ethics that they fear not only terrifying things that are beyond human strength, but also those that are on the human level:

brave people will be frightened by such things, but in the right way, and they will endure them as thinking dictates. Their aim is to do what is noble, since that is the goal of virtue … People who endure and are frightened by the right things and for the right reasons, as well as in the right manner and at the right times – and likewise for what emboldens them – those people are brave. (Susan Sauvé Meyer’s translation)

This concession is crucial for Aristotle’s understanding of courage, both because he admits that the brave person does experience fear while acting courageously, and because it reveals the complexity of his view. His point is not simply that courageous people bear their fears well, but that they do not see terrifying things necessarily as reasons to avoid courageous action. The brave person instead follows reason and withstands frightening things in the right way and for the sake of the noble.

Fear can focus the mind on the steps needed to avoid danger

Readers sometimes struggle to understand Aristotle’s account: his language of one who ‘endures’ frightening things makes it seem as if courageous people must resist and overcome their fears. If that’s the case, then courage would involve the sort of inner turmoil that Aristotle plainly denies virtuous people experience. He insists that, ‘if you endure frightful things and are pleased by that – or at least not pained – you are brave’ (Meyer’s translation). But Aristotle does not think that fear is something to be fought against or suppressed, resulting in inner turmoil. Instead, courageous people incorporate their fear into their activity by putting it in its proper perspective and harnessing it to achieve a noble end. They fear well.

Fear can focus the mind on the steps needed to avoid danger. For Aristotle, feeling the proper, virtuous sort of fear does not move us to avoid danger at all costs, nor to rush recklessly into danger, but rather to take appropriate precautions (such as putting on armour) in attempting to realise a noble goal. Brave people do not need to struggle against a desire to flee from a noble death. Instead, their fear alerts them to the salient dangers in their environment, and they take prudent measures to meet with those dangers while acting for the sake of the noble, as reason directs.

Unlike a bronze statue, Aristotle’s brave person is not invulnerable. They recognise, painfully, that pursuing the right course of action renders them vulnerable to real losses. Courageous people stand out for their ability to choose the noble at the cost of other goods in their lives – including, at the extreme, their very survival. Aristotle, then, shows us something difficult but admirable: a way to feel fear that converts our impulse to retreat from pain and loss into a rational advance towards the preservation of virtue. We can apply this lesson as we make tough choices far from the battlefield, including when defending the integrity of our political communities. Uneducated fear motivates citizens to choose security and material or social advantages at the expense of justice. Hence why tyrants, in Aristotle’s time as much as ours, use fear and threats to wellbeing to maintain power. If we are going to have a political community that can make the sacrifices required to resist injustice, then some members of that community need to know how to feel fear well.