It’s not uncommon to hear people on opposite sides of an issue invoke ‘dignity’ when defending their positions in political debates. Take assisted dying. Both advocates and opponents appeal to dignity – but they mean very different things by it. For one side, dignity means having the right to choose death. For the other, dignity means ensuring that the ‘right’ to die doesn’t become a ‘duty’ to die. How can one word inspire such opposing conclusions and still matter?

Since dignity is wielded by people with completely different stances on an issue, some suggest that the word is little more than a vapid, outdated concept. But it’s possible to reclaim dignity’s significance by reckoning with its troubling historical roots. It’s in reckoning with and reclaiming – rather than trying to paper over or reinvent – dignity’s origin story that we might revive its instructive power for contemporary living.

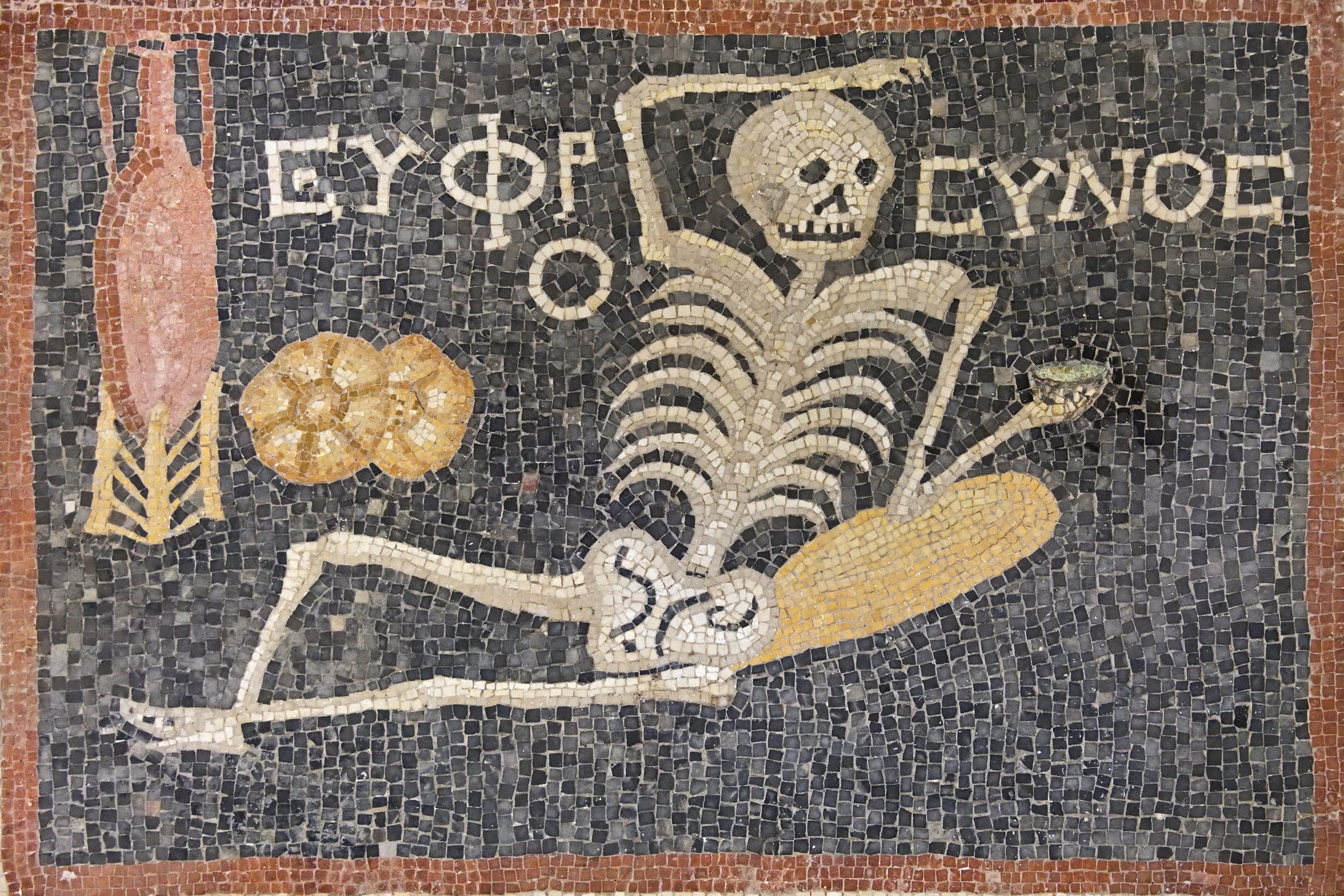

Although Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares that ‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights,’ the idea that dignity could be something we’re all born with couldn’t be further from how dignity was originally understood. During the Greco-Roman period, dignity (or dignitas) wasn’t universal. Instead, it signified a kind of hierarchical humanhood. Educated male landowners were part of a dignified class of people, while women and slaves were of a lesser rank.

Over time, dignity shifted from something that conferred societal rank to something that named a subtler primacy. For Cicero in ancient Rome, dignity hinged on a person’s moral rationality. For Immanuel Kant in 18th-century Germany, dignity hinged on one’s capacity for reason. These prerequisites – whether autonomy, rationality, or the capacity for reason – meant that women, those with mental or developmental disabilities, infants, and nonhuman beings were all unable to access dignity.

Throughout history, then, dignity has been predicated on the exclusion of some Other. Reckoning with dignity’s harmful origin story means we must grapple with the reality that to be regarded as fully human and therefore deserving of dignity has always meant, in some way, that dignified persons were set apart from someone or something deemed ‘lesser’.

Hannah Arendt’s understanding of dignity provides us with an approach for how to confront this harmful legacy. By characterising dignity as conditional, Arendt invites us to consider the possibility that if someone’s dignity goes unrecognised, its existence has no practical significance. Arendt’s conditional dignity offers a corrective to centuries of theorising that romanticises dignity as an inherent, inborn or essential quality unique to human beings.

As John Douglas Macready writes in Hannah Arendt and the Fragility of Human Dignity (2017), viewing dignity as conditional ‘emphasises the co-responsibility of individuals and political regimes to insist upon the right of human beings to have a place in the world.’ That is, we all have ‘the right to belong to a political community and never to be reduced to the status of stateless animality’. But a perpetual risk exists under the rubric of conditional dignity: the right to belong could go unrecognised, thereby rendering dignity practically impotent or politically ineffectual.

There is a lot to learn from Arendt’s understanding of dignity. First, we neither possess nor give dignity. And instead of being born with an innate dignity, its existence hinges on external conditions. We must, therefore, continually practise dignity. Our practices seed the ground for the possibility of dignity. It’s ‘through speech and action’, as Macready writes, that we practise the possibility of dignity. To practise something means we might try (and try again) – but we are never guaranteed a particular outcome. There’s always a risk that our speech and actions miss the mark.

Indignities emerged from the slow accumulation of otherwise banal micro-moments

This brings me to the next lesson we can learn from Arendt’s understanding of dignity as conditional. Individual words, actions and behaviours are only a few of the conditions in a sea of factors that seed or impede the experience of dignity. Our individual practices, no matter how well-intended, are always situated within larger power relations (such as capitalism, racism, etc). Power asymmetries affect how individual practices are perceived and received.

Given these complexities, the primary practice involved in doing dignity is what I call ‘minding the slash’. This is when we honour the fragile space between dignity and indignity, symbolised by the slash in words like ‘un/dignified’ or ‘in/dignity’. The slash serves as a deliberate reminder that in/dignity’s emergence is delicate. Indignity is always possible, despite our best intentions. To mind the slash is to understand that dignity is not something that is bestowed or given. It is conditioned by a host of factors – many of which are out of our immediate control.

But many smaller un/dignified practices are very much within our control, and these are crucial to pay attention to when doing dignity. In my own study of the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, what characterised un/dignified care were experiences that emerged from the cumulative consequences of ordinary ‘micro-moments’ that patients and their loved ones endured: a hurried nurse forgetting to draw the curtain closed while bathing a patient; a doctor’s reluctance to enter a patient’s room because they don’t speak the same language; a minor administrative error that results in delivering the wrong hospital dinner. There often wasn’t a single major event that caused someone to experience undignified care. Rather, indignities emerged from the slow accumulation of otherwise banal micro-moments.

Micro-moments might involve little more than a split-second glance, an unintentional dismissal, or accidental mispronunciation. These un/dignified micro-moments can precipitate a cascade of in/dignity, especially once larger bureaucratic forces rear their heads. Attuning to micro-moments requires us to regard each and every exchange as potentially contributing to a much larger inventory of un/dignified experiences.

We can’t self-care our way out of these communal legacies

While we must remain perpetually attuned to the immediate, fleeting, everyday micro-moments that accrete over time to seed un/dignified experiences, we simultaneously should remain curious about the long arc of history from which a micro-moment emerges. To do this, we can cultivate curiosity about the wide range of long-standing hierarchies and pre-existing conditions that have shaped the situations we find ourselves in. In the US, certain populations are caught in what the social scientist Alondra Nelson in Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination (2011) calls a ‘dialectic of neglect and surveillance’ – a dynamic in which people are either overlooked or watched too closely. This push-pull is the result of decades of institutional harm to people of colour in the US. Over time, the dialectic of neglect and surveillance has led to a host of in/dignities for particular communities. Our individual words and actions are always situated within that dialectic.

Think about a micro-moment when your words or actions missed the mark or failed to cultivate a dignified effect. Instead of internalising that micro-moment as a failure, be curious about the other conditions that may have resulted in your good intentions falling flat. Be curious about how previous experiences or legacies of trauma may have collided with your otherwise good intentions. Be curious about why what feels like a good intention to you might be experienced as a harm. Staying curious helps to keep the focus on dignity’s conditionality rather than selfishly fixating on what we did or didn’t do right.

Mindful of the slash, we remain curious about historical inheritances. They’ve lodged themselves in our own and others’ bodies and psyches for centuries. We can’t self-care our way out of these types of communal legacies, either. Social arrangements do, indeed, structure how we experience the world.

What makes doing dignity even more difficult is that in/dignity’s unpredictability always sets us one step behind. We never fully know until it’s too late whether a word, act or disposition has seeded in/dignity. We’re continually outpaced by consequences. What this means, practically, is that we have to intentionally build in time for what the philosophers Walter Mignolo and Catherine Walsh in On Decoloniality (2018) call ‘thought-reflection-action, and thought-reflection on this action’.

Thought-reflections on our actions do not necessarily produce revisions, remedies or fixes. Rather, we engage in thought-reflection on un/dignified actions as part of an ongoing practice of tinkering. As the researchers Annemarie Mol, Ingunn Moser and Jeannette Pols write in their book Care in Practice: On Tinkering in Clinics, Homes and Farms (2015), in a world ‘full of complex ambivalence and shifting tensions’, reflecting and tinkering provide us with opportunities for ‘attentive experimentation’. Tinkering remains ‘attentive to such suffering and pain, but it does not dream up a world without lack.’ As the disability researcher Myriam Winance puts it, to tinker is to

meticulously explore, ‘quibble’, test, touch, adapt, adjust, pay attention to details and change them, until a suitable arrangement (material, emotional, relational) has been reached.

Over time, our tinkerings contribute to a broad repertoire of responses and recognitions that, depending on the nuances of a particular situation, seed the possibility of in/dignity.

Consider where we began: assisted dying. Regardless of your current position on assisted dying, if you haven’t already, cultivate curiosity about how the evidence you use to support your stance on the matter might have unintended consequences for others. Wonder about what hierarchies your evidence for or against assisted dying (unintentionally) reifies. Specifically, if you’re an advocate of the ‘right to die’, under what conditions would you say a life is not worth living? What conditions might emerge if politicians legislate what makes a life worth living? For whom might these conditions actually do harm, even if unintentionally?

Now consider what conditions might help to seed the ground for flourishing – even at the end of life. What tinkerings do we need to practise in order to cultivate such conditions? What mundane micro-moments, when wedded to broader legislative backing, might lay the groundwork for a dignified death? Above all else, remember to mind the slash. Stay curious about the consequences of what you, at least for now, call dignified care.