The power of diagnosis is becoming more potent. In 2022, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the ‘bible’ of mental health professionals, appeared on The Wall Street Journal’s bestseller list for the first time. It was also the top-selling psychiatry book on Amazon. Five editions have been published since 1952, and the latest, the DSM-5-TR (2022), is perhaps the most popular of them all. Why? Is it the promise that science can assess and understand human suffering? Is it the belief that this understanding can help us find specific, appropriate and effective treatment for our problems?

These are tempting but misleading promises. Human suffering is not defined by abstract categories. It does not exist independently of humans who are suffering. Useful as the DSM is, any project that seeks to list and categorise psychological problems in terms of some deviation from a definition of what is ‘normal’ runs the risk of forgetting that disorders do not appear out of thin air. They have their own history. They are also part of our histories. Moreover, they do not remain constant; they change just as we change.

From the moment it was conceived in the mid-20th century, the DSM was hailed by many as a liberating and revolutionary scientific project. Not everyone has agreed. It and other diagnostic tools have also been criticised for being vehicles of corporatised medicine, products of bureaucratic health systems, riddled with false categories, and for forgetting that psychological suffering is connected to the society that produced it. However, within this debate, the personal histories of those who actually experience suffering are often overlooked.

Human experience is distributed, non-specific, and flows in time. The checklist-style organisation of the disorders that populate diagnostic manuals and tests – including online questionnaires, mental health apps and personality ‘inventories’ – tend to forget that people have some awareness of themselves as agents in a timeline that is coming from somewhere (the past) and going towards somewhere (the future). This distinctly human feature of our experience, its historicity, has been at the centre of the work of philosophers like Martin Heidegger and psychoanalysts like Jacques Lacan. Less a question about the factual specifics of one’s timeline (what happened when and where), ‘historicity’ in philosophy refers to the fact that we are constantly creating and re-creating self-narratives. This is how we try to make sense of our lives as we move along the myriad pathways that connect our past to our future. These meandering and confusing pathways, full of dead ends and false connections, often contribute to our suffering.

It’s tempting to believe that we can see ourselves objectively reflected in the diagnostic criteria and checklists of ‘bibles’ like the DSM, but our individual stories and anxieties elude easy diagnosis because they do not exist independently of our history or our attempts to articulate them, make sense of them, and fit them into the identities we are constantly trying to form of ourselves.

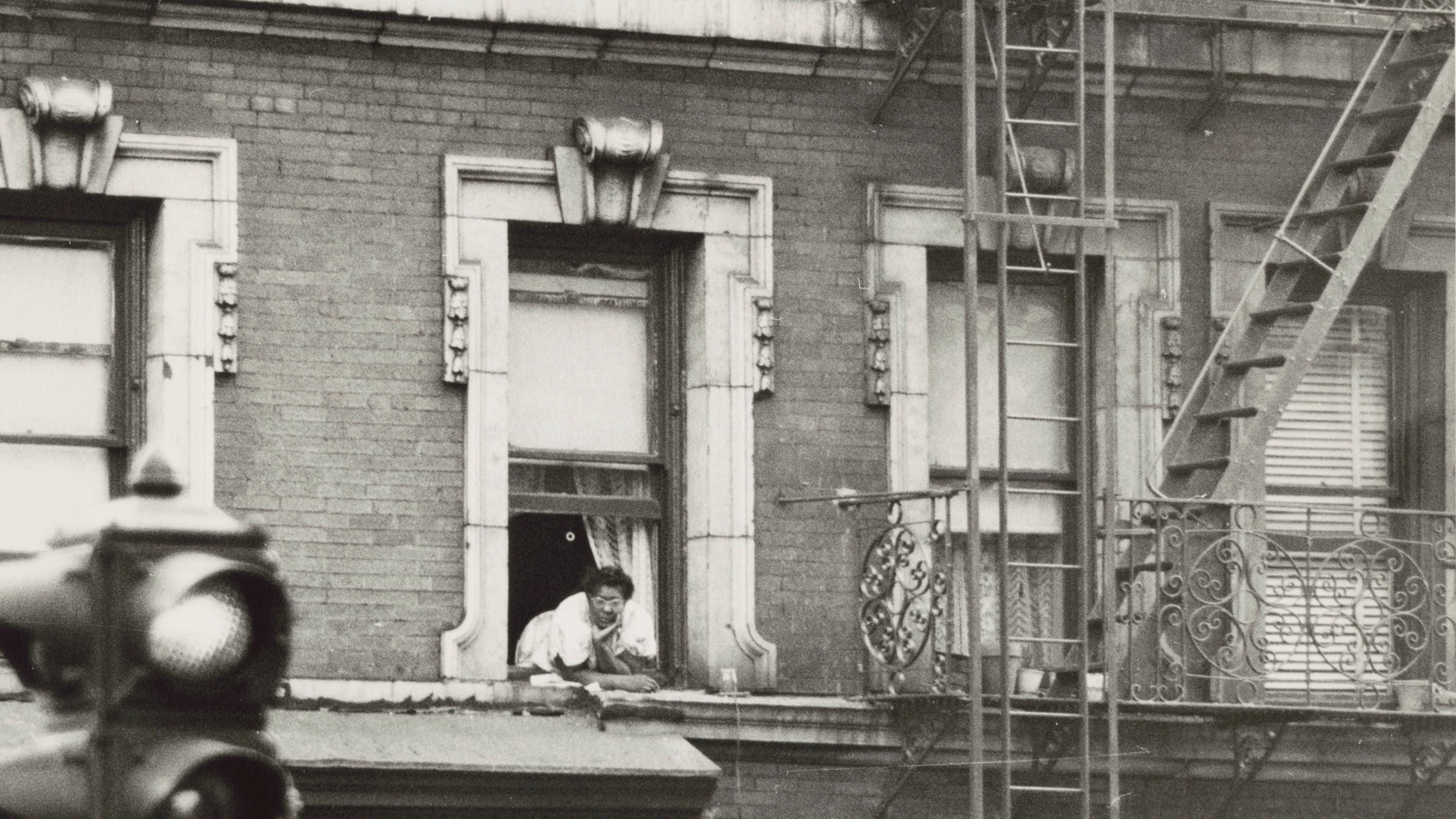

I am a psychoanalyst working in London. The people who come to see me, mostly self-referrals, are seeking help with those articulations, that sense-making and indentity-construction. Robert (not his real name) first came to see me when he was in his 30s. He came because he was worried about his job at an art gallery, where he felt like an intruder, having nothing in common with his colleagues. Just like his experience in previous jobs, he had a deep, debilitating fear that colleagues and bosses were always watching, waiting for him to make a decisive mistake. This fear would make him freeze. He couldn’t think. He wanted to disappear.

‘I disappear,’ he tells me. ‘I look at the mirror, and I am not there anymore.’

‘What do you mean, disappear?’ I ask.

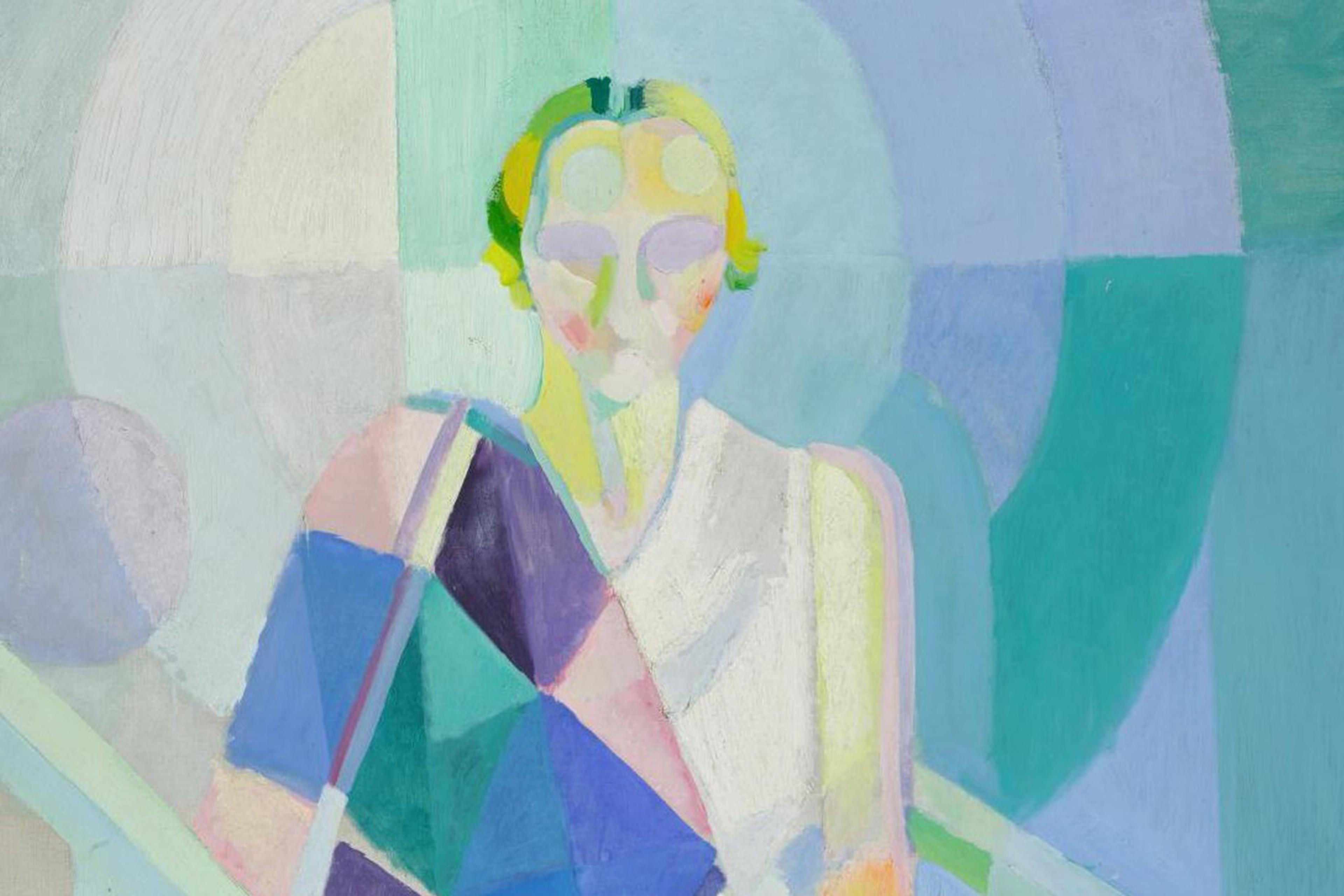

He looks uncertain. ‘I don’t know how else to describe it. When I am in this state of worry and fear, the face I see in the mirror disintegrates. It’s not my face anymore. It becomes an assortment of features. An eye here, another eye, a nose, an ear… I cannot recognise myself. I can’t see a face. It’s empty. I don’t exist anymore. I just freeze.’

‘What does this mean?’ I ask again.

‘I see disconnected features. I stay there, in vain,’ he looks at me, ‘for long periods of time.’ He pauses. ‘For hours,’ he admits, lowering his gaze.

So, there it is. Robert is finally able to give me a glimpse into his suffering. At this moment, I could try to turn his symptoms into a diagnosis. Significant distress? Yes. Impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning? Yes. Preoccupation with physical appearance? Yes. Repetitive behaviour, such as mirror checking? Yes. Indications of an eating disorder? No. Diagnosis? ‘Body Dysmorphic Disorder’, coded F45.22 in the DSM-5-TR. The clinical picture painted by the DSM almost seems as though it was written for Robert.

The DSM was, from the beginning, organised according to results produced by statistical tools. As a scientific project, it suggests that we can and should speak only about things that can be observed and assessed clearly. This same idea appears in an array of psychological tools and instruments that seek to provide objective accounts of human experiences. These include the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), currently in its 11th revision, and the National Institute of Mental Health’s Research Domain Criteria (RDoC).

How are these accounts made? How can you assess mental illness, human suffering and distress in an objective way? The key is to quantify what you see with the help of simple unbiased tools such as structured interviews or questionnaires. These tools can reveal aspects of how large groups of people think and feel about the world and themselves. Through this data, patterns and categories emerge. Almost every category and criteria in our diagnostic manuals has been defined by these tools, which ask questions like:

On a scale from 0 (very bad) to 9 (very good) how would you assess your overall mood this week? What about last week?

Using a scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree) indicate your degree of agreement to the following statement: ‘I cannot find joy in anything any more.’

The underlying principles and intentions of these kinds of questions, and the tools they come from, are noble. And yet, things are not so simple. By representing our experience of something like sadness with objective data, are we being unfaithful to the actual phenomenon of being sad? Our sadness has a history and meaning within our own history. It started at some point, it has changed, it keeps on changing. Our sadness cannot be faithfully represented ‘using a scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree)’ or using any number of measurements on any kind of scale. By taking a snapshot of a ‘disorder’ – that is, by removing any reference to its context and history – we are forcing it to conform to concepts and tools that are unfit for purpose. In the name of scientific objectivity, we violently transform multifaceted and complicated notions into a-historical sets of data.

It’s all about history.

I ask Robert to tell me more. When did this start?

Robert cannot say exactly. He feels he has always had difficulty drawing faces – even seeing faces. When he looks in the mirror, he tells me, it is as if his own face is stripped of meaning.

‘Stripped,’ I repeat.

‘Yes,’ he says. ‘And not just the face. The same happens with bodies. It is as if they are stripped of meaning, too. I end up drawing like Lucian Freud or Francis Bacon.’

‘Is that a problem?’ I ask, trying to ease the tension.

‘I didn’t intend it in this way,’ he says.

I invite him to say more about the human body. ‘Nudes are stripped from clothes,’ I offer.

‘Indeed,’ he says, pausing.

This brings a memory.

‘I am a bit embarrassed,’ Robert admits.

He remembers something that happened when he was around 13.

Entering adolescence, fascinated and overwhelmed by his sexuality, Robert started making small erotic drawings, vaguely involving himself and his sister who was around 15. One day, his mother found the drawings. Appalled, she decided that the best way to deal with this was to call for a family meeting. He watched in horror as she circulated the drawings, spoke at length about them, and publicly humiliated him. She made him ask for forgiveness from his sister, and then made him destroy the drawings ceremoniously in front of everyone, including his father who said nothing but kept nodding. When all this was over, he was ordered back to his room. There he cried bitterly for hours and later defiantly re-drew everything from memory. He carefully hid them somewhere, and insists that he hasn’t looked at them ever since. For him, they don’t exist any more.

Robert’s difficulties with faces and bodies had a precursor. Behind his inability to discern the meaning of faces was a past traumatic event.

Through the logic of the DSM, Robert’s suffering is defined by the precise form it takes at the specific point in time an assessment is made. In this moment, he may be pigeonholed as F45.22 or similar. A DSM diagnosis like this is a single snapshot of one’s suffering. It’s accurate, but the history of that image is left out: Robert’s humiliation and rejection by his family; the pain he felt; his guilt over his awakening sexuality; the fear that what he loves most – drawing with his pencil – will lead to him being ostracised and lost.

Robert had not been allowed to process this in a way that would help him discern its meaning. His suffering has an origin, and there are pathways leading from that origin to his current complaint. Robert’s ‘disorder’, the hours he spends in front of the mirror and the difficulty to discern and recognise his face, may be known and described accurately by the DSM with an appropriate code. But this disorder has a past that is lost to the user of a diagnostic manual.

At a moment when the DSM has become a bestseller, it’s important to consider that a ‘snapshot’ diagnosis, useful as it might sometimes be, represents a disconnected instant in one’s life. The paradigm of the snapshot diagnosis via quantification reveals its limits when we consider the historicity of our lived experiences and recognise that these cannot be represented by sets of a-historical data.

Psychological suffering is fundamentally unquantifiable. It develops across myriad meandering pathways. It shifts, changes, transforms. It invites us to discern meaning in our history, even as that meaning threatens to escape, overwhelm and confuse us – even as our very faces disappear in the mirror.