‘I am Isabel, and I am an alcoholic,’ the woman said, introducing herself at the group therapy session. ‘I haven’t had a drink for 22 years now.’ One of us, Chrysanthi, was attending the session as a clinical trainee. With genuine curiosity, she asked: ‘What makes you an alcoholic if you haven’t had a drink for almost a quarter of a century?’ Isabel looked at her, slightly perplexed, and said: ‘It is a disease. I have it in my brain.’

For Isabel (whose name has been changed here), understanding her addiction as a brain disease was liberating. Her experience illustrates how the brain-disease model of addiction, first articulated in 1997 by the American psychologist Alan Leshner, has likely helped some people who are struggling with addiction to experience less guilt and self-blame. The model gave scientific legitimacy to an older concept, popularised by Alcoholics Anonymous, which had framed addiction as a chronic disease that required spiritual and communal support, rather than punishment and shame. Stripping away the spiritual and moral elements of that concept, the brain-disease model aimed to eliminate the stigma surrounding addiction once and for all: science would eventually prove that addiction is a matter of brain dysfunction, not related to character flaws.

Indeed, reducing stigma was one explicit goal of the brain-disease model of addiction. At the same time, it heralded a novel way of explaining addiction, as a chronic and relapsing condition caused by alterations in the structure and function of the brain. It emerged from a broader cultural shift that started in the 1960s and culminated in the 1990s, with the advent of neuroimaging techniques, and that increasingly prioritised neuroscience in understanding mental disorders. The brain-disease model shaped research priorities worldwide. Deciphering the biological causes of addiction was expected to lead to more effective treatments, including precise interventions targeting the specific neurobiological or neurochemical processes involved.

Nearly three decades later, it’s important to evaluate how well the model has delivered on its promises. Is the brain-disease model still the best way to think about addiction? Do the outcomes produced by the model justify educating entire generations of patients, families and clinicians to view addiction primarily as a problem of individual brain pathology?

The short answer is that the brain-disease model has not delivered. After countless studies finding weak neurobiological differences between people with substance use disorders and those without them, no reliable biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis or personalised treatment have been identified. The most effective treatments for addiction are either psychosocial – including peer support groups and therapy – or were developed well before the emergence of the brain-disease model. For instance, methadone was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for opioid use disorder in the 1970s, and naltrexone was approved in the 1980s. Buprenorphine was approved in the early 2000s, just as the brain-disease model was gaining traction and without a direct relationship to it.

While personal accounts like Isabel’s are not uncommon among people with addiction, the impact of the brain-disease model on stigma is more complex than is often assumed. Recent research indicates that acceptance of this model does not substantially reduce stigma in the general population, nor does it lessen support for punitive responses to addiction. The idea that someone with addiction has a brain disease might even reinforce stigma in some cases, contributing to pessimism about one’s chances of recovery and a lower sense of personal agency. Medicalising a condition does not automatically destigmatise it; in fact, disease labels themselves can be highly stigmatising, as seen in conditions like HIV/AIDS.

There were also fundamental conceptual problems with framing addiction as a brain disease in the first place. The brain-disease model’s dual function as both an etiological theory and a tool to reduce stigma has compounded two distinct questions: whether addiction is a brain disease, and whether labelling it as such reduces stigma. This has led to conceptual confusion in that questioning the validity of the model is often conflated with endorsing a moralistic view on addiction or perpetuating stigma. However, a scientific theory must be evaluated on its own merits. That is, on whether it provides a necessary and sufficient explanation of the phenomenon, and whether it generates predictions that can be empirically tested.

Addiction was often compared to conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and stroke

Evaluating the brain-disease model’s scientific standing reveals a deeper source of confusion: it is not entirely clear what it means to say that addiction is a brain disease. Does it simply mean that, since addiction is a mental disorder, and all mental activity resides in the brain, then addiction must also be a ‘brain disease’? Or does it mean that addiction is akin to conditions that are universally recognised as brain diseases, such as brain cancer or Parkinson’s disease?

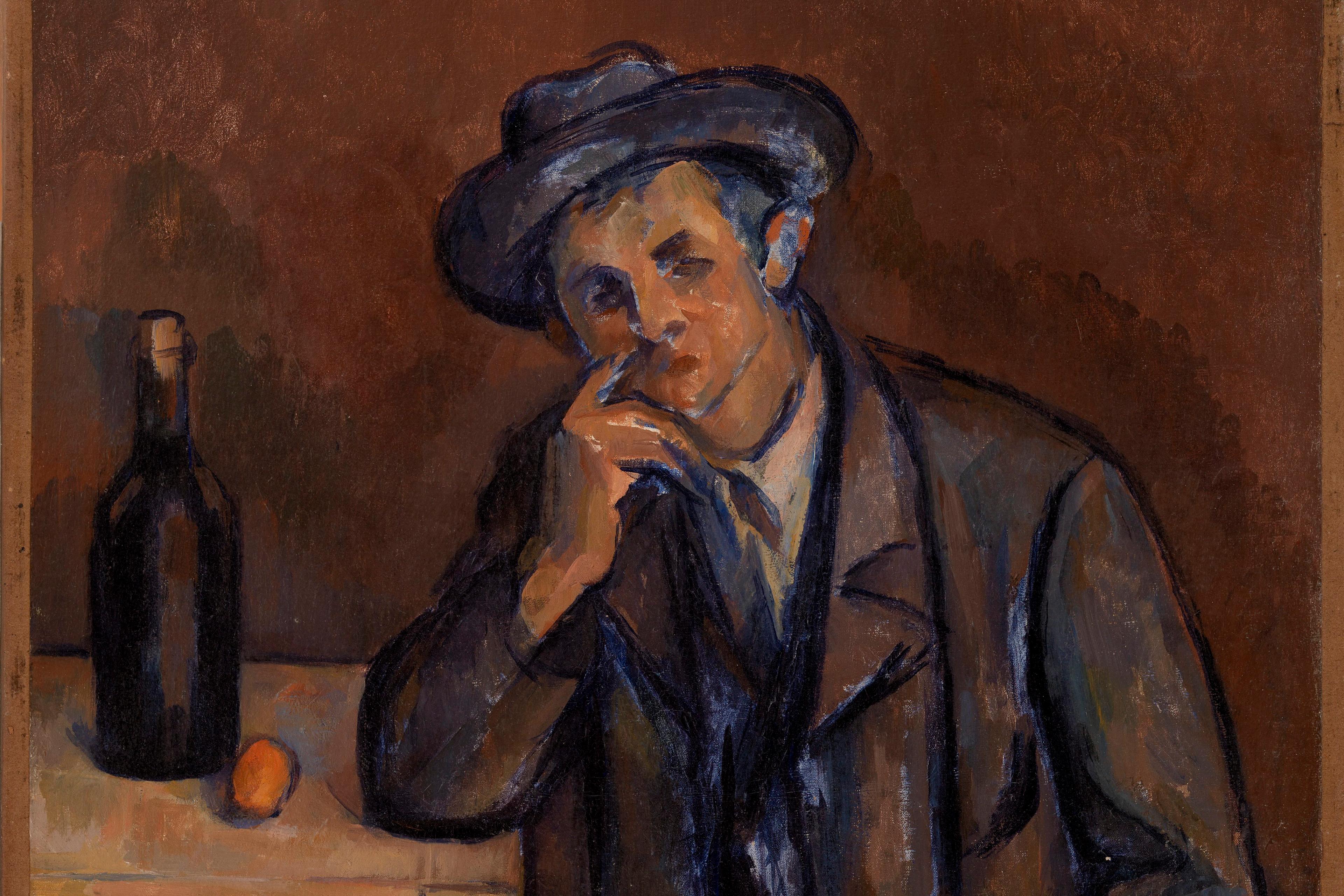

Leshner’s early formulation of the brain-disease model closely aligns with the latter view. In the early 2000s, addiction was often compared to conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and stroke. It was thought to result from a genetic vulnerability to the effects of drugs, combined with drug-induced changes in brain regions involved in reward, impulse control and negative emotions. These long-lasting brain changes were viewed as the primary drivers of relapse and became key targets in the search for new medications.

The core elements of the brain-disease model of addiction are effectively captured in the ‘hijacked brain’ metaphor. Popular in both scientific and mainstream discourse, this metaphor suggests that chronic drug use ‘hijacks’ the brain’s motivational system, making further drug use ultimately irresistible, despite its negative consequences.

But even these fundamental elements of the brain-disease model have been challenged. The extent of the loss of control in addiction has been questioned, as symptoms are highly responsive to psychosocial interventions. For instance, contingency management, which uses positive reinforcement to encourage abstinence, is highly effective across a range of substance use disorders and remains a first-line treatment for disorders with no approved medications, such as stimulant use disorders. Unlike paradigmatic brain diseases like brain cancer, addiction can be modified by one’s desire to get better. And while substance use disorders can indeed be chronic and difficult to treat, there is also evidence that many people not only recover, but do so without experiencing relapse. These findings challenge the view of addiction as inherently chronic and relapsing.

What’s more, brain changes associated with addiction have proven to be neither reliable nor specific enough to be clinically meaningful. At present, there is no neural signature that would allow clinicians to distinguish the brain of a person with addiction from that of a person without addiction. Some proponents of the brain-disease model have argued that, given enough time and resources, neuroscience will eventually lead to mechanistic insights and more effective treatments. Yet, after decades of intensive research, such optimism seems unrealistic.

With the core elements of the brain-disease model increasingly difficult to defend on empirical grounds, its proponents often take up the broader view that addiction must be a brain disease because it involves the brain. No scientist seriously disputes that the brain is involved in addiction (or in any mental disorder), so this argument is logically trivial. Recognising that all mental activity involves brain activity, without identifying specific, consistent and targetable brain dysfunctions, does not advance the understanding or treatment of addiction. This broad view also implies that any process that gives rise to symptoms through neurobiological mechanisms must qualify as a brain disease. However, negative life events such as separation or loss can also trigger or worsen depressive symptoms, most likely through a cascade of neurobiological changes, and no one would consider these events brain diseases.

At its core, the brain-disease model was meant to explain addiction in terms of objective brain data, sparing us the trouble of trying to sort the messy, subjective aspects of human experience. It has fallen short likely because it overlooked a fundamental reality: you cannot take the ‘mental’ out of mental disorders. Any brain changes that are observed in mental disorders, including substance use disorders, derive their dysfunctional status not from a comparison with normal brain function, but from the mental dysfunction that they supposedly produce.

Some researchers have suggested that brain changes associated with addiction might not even indicate an underlying brain pathology. For instance, the neuroscientist Marc Lewis has proposed that these brain changes might instead reflect the neurobiological imprint of normal learning processes going awry at the behavioural level. These learning patterns may become entrenched not because of brain damage, but because the individual lacks access to alternative sources of reward – such as meaningful relationships, educational opportunities or stable employment. This is just one of a broader set of complementary explanations that do not solely rely on inherent or irreversible brain abnormalities to account for addiction.

We already know a great deal about what is likely to help and have an impact on people’s lives

Persistence in framing addiction as primarily an individual brain problem obfuscates the broader societal factors at play, including those known to be major drivers of addiction, such as poverty, systemic racism and social inequality. Take, for example, the opioid use disorder epidemic in the US: the major forces that drove this crisis were largely social rather than biological, and systemic rather than individual, including aggressive pharmaceutical marketing for prescription opioids, as well as deindustrialisation and poverty. This suggests that effective responses to addiction require addressing the structural conditions that produce and sustain vulnerability, rather than chasing a yet-to-be-identified brain pathology.

In the quest for scientific breakthroughs in treating addiction, we should not forget that we already know a great deal about what is likely to help and have an impact on people’s lives. Substantial evidence supports measures like free and unconditional access to medical and psychological treatment, access to stable housing, and enhanced community support to combat loneliness. Yet these measures remain insufficiently implemented.

In the months after they met, Chrysanthi got to know Isabel better, coming to understand that the brain-disease model had offered her a useful narrative at a time when she most needed it – when Isabel was struggling with feelings of guilt, self-hatred, and alienation from herself and from others. But it is possible to help people alleviate these feelings without suggesting that addiction is an irreversible part of who they are.

As Isabel returned to the group, it became clear to both of them that what sustained her recovery was not the particular framework she used to understand her experience, but finding meaning again and feeling seen, heard and understood by others. This is what psychiatry risks losing sight of in its relentless pursuit of pinpointing the exact brain pathology: interventions that make people feel and get better do not always need to resort to biology.