If you were in a burning building and forced to choose between saving a child or a painting by Picasso worth millions of dollars, which would you choose? If you care about saving as many lives as possible, the philosopher William MacAskill – associate professor at the University of Oxford and a co-founder of the so-called ‘effective altruism movement’ – believes that you should save the Picasso. Why? Because you could sell it and donate the proceeds to charities that could save thousands of children’s lives.

But you probably couldn’t bring yourself to do it. The effective altruism movement, which aims to help others as much as possible as effectively as possible, has a certain undeniable logic. So why hasn’t it caught on? A key reason is that it clashes with basic human morality.

Toby Ord, a moral philosopher at Oxford and co-founder with MacAskill of Giving What We Can, one of the first effective altruism organisations, has experienced this first-hand. In 2015, he told The Guardian that he found it relatively easy to convince people to give more to charity, but much harder to convince them to stop giving to their beloved local causes and instead give to more ‘effective’ charities – organisations that might feel more remote but that would actually do more good for many more people elsewhere.

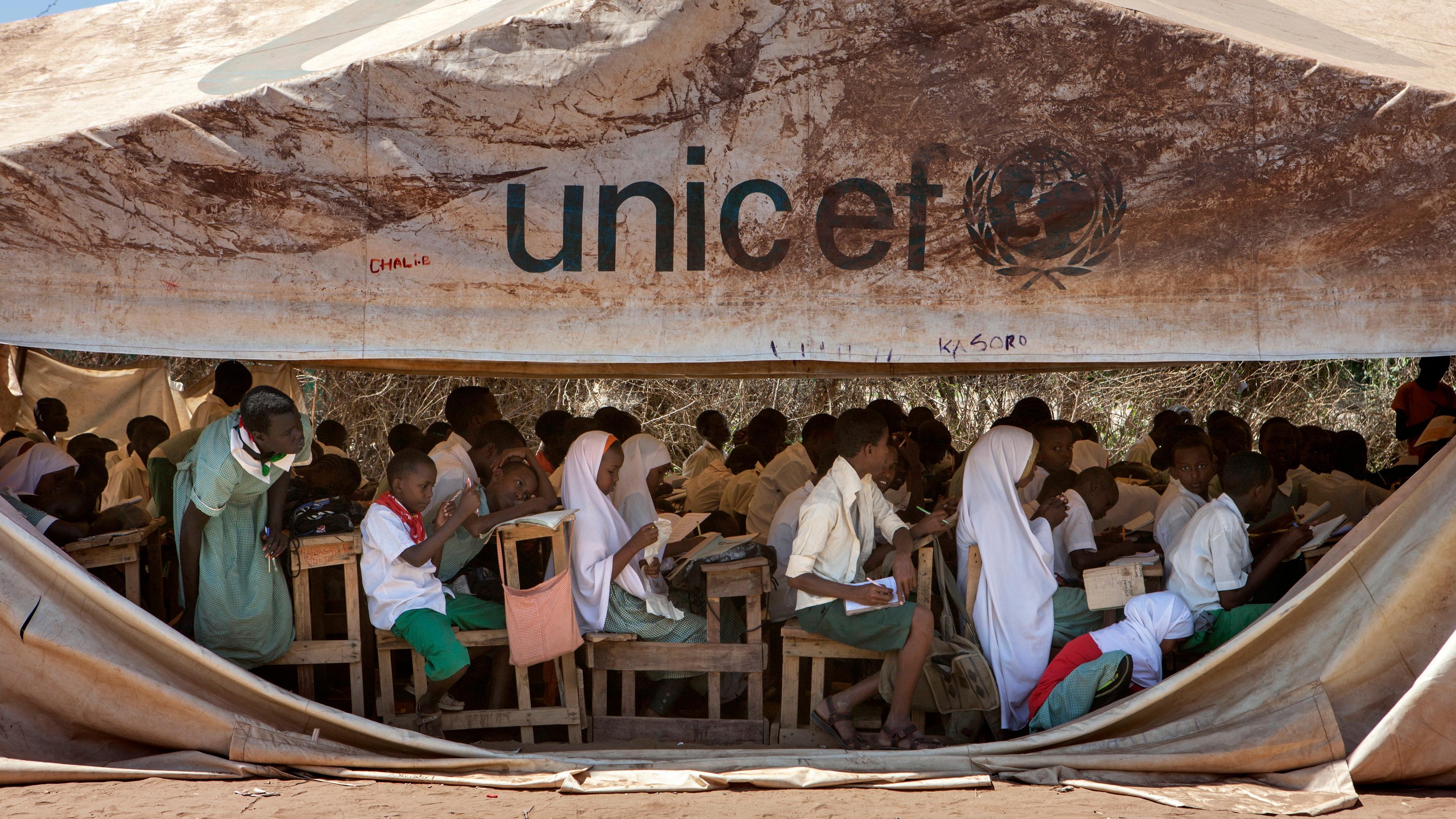

For a sense of what more effective giving looks like, GiveWell, a charity research organisation, gives a striking comparison, estimating that an international charity focused on preventing and treating malaria in developing countries saves a human life for every $2,300 it spends, whereas one of the most promising childhood education charities in the US spends $10,000 or more per student every year, for the chance not to save lives, but to improve academic outcomes.

At its core, effective altruism’s rational approach follows an ethical philosophy called utilitarianism that weighs the costs and benefits of actions. Most people are at least somewhat in tune with this way of thinking, as illustrated by responses to the classic ‘trolley problem’, in which a runaway trolley is about to run over five people on a track, unless you save those five by flipping a switch to redirect the trolley to a different track where just one person is located. Because flipping the switch would save five lives at the cost of one life, the effective altruist says you should flip it. And in numerous studies, most people say that they too would flip the switch. Applying this same logic to charitable giving, it makes more sense to donate your money, or give your time, where it will have the largest possible beneficial impact.

If people are prepared to flip the switch, why aren’t they prepared to optimise their charitable giving?

It turns out that most people aren’t strict utilitarians. Feelings get in the way. If the trolley problem is framed slightly differently, such that to save five lives you’d have to actively push someone in front of the trolley, killing that individual in the process, few people say they would do it. Even though the costs (one life lost) and the benefits (five lives saved) are the same as before, there’s something repugnant about physically forcing someone to their death, and these feelings overpower most people’s moral judgments.

Research suggests that emotions also skew people’s judgments about charitable giving. Consider an experiment from 2018 led by Jonathan Berman, associate professor of marketing at London Business School, in which hundreds of volunteers read about a woman who was deciding which of two charities to donate to – one less effective, but that she had an emotional connection to because it helped homeless people in her community, and the other far more effective, but emotionally distant while devoted to feeding children in Africa. Although the volunteers recognised the second charity as more effective, they believed it would be better for the woman to donate to the option for which she had an emotional connection.

One particularly strong source of emotional feeling that utilitarianism, and therefore effective altruism, collides with is family loyalty – a cornerstone of human morality. Effective altruism is committed to impartiality – giving equal moral weight to all human lives. The principle of impartiality is reasonable and codified into many countries’ legal systems. But in everyday judgments, many of us make exceptions, for instance giving more moral weight to family members and friends over strangers, and to fellow citizens over noncitizens.

Even advocates for effective altruism find it a challenge to uphold the philosophy when faced with the pull of family bonds. For instance, the philosopher Peter Singer, professor of bioethics at Princeton University, is a prominent effective altruism champion who gives a significant part of his income to charity. But when his mother developed Alzheimer’s disease, he spent large sums of money on her care – money that could arguably have been spent more effectively improving the welfare of more people elsewhere in the world.

Behaviour such as Singer’s motivated Ryan McManus, a doctoral student in psychology at Boston College, and his colleagues to examine the role that family relationships impose on our sense of moral obligations. They found that research volunteers rated a hypothetical person who helped a stranger as more morally good compared with a different person who helped a relative. However, when they heard about a hypothetical person who was forced to choose between helping either a stranger or a relative, the volunteers rated the person more morally good if they chose to help their relative – the opposite of the first result.

The results show the power of family loyalty over our moral judgments. Many of us feel a special obligation to help family members that we don’t feel for strangers. ‘When you’re not forced to make a choice between family and stranger,’ says McManus’s co-author Liane Young, ‘the person who helps a stranger seems to get this extra credit for doing something that is out of their bounds of duty.’ But at the same time, people who choose strangers over family get blamed for violating their obligations.

These findings are a serious problem for effective altruists. Their cold rational approach simply doesn’t come naturally to most people, and we’re distrustful of – or even disgusted by – others who adopt it. In a study in 2018, participants rated a grandmother who donated her winnings to a malaria-fighting charity rather than to her grandson (so he could fix his car) as less trustworthy and loyal than if she’d made the opposite decision. In another study posted online in April 2020 but not yet peer reviewed, participants rated a person who used the effective altruism approach to charitable giving as lower in moral character, and a worse friend or neighbour, than one who’d used empathy to drive decision-making. Similarly, to return to the hypothetical building on fire, if you’re like most people, not only would you not be able to bring yourself to save the Picasso over the child, you’d consider someone who could to be abhorrent. Had Singer neglected his dying mother in favour of strangers, instead of putting her needs first, he likely would have been viewed as a ‘moral monster’, says McManus.

In theory, if we all adopted the approach espoused by effective altruism, then the world would indeed be a better place – more people would benefit by a greater amount, especially those most in need. But clearly the logical approach to helping others is unnatural, even distasteful, to many people. So what to do in our own lives? The research can’t tell us whether it is ethically correct for people to favour complicating factors such as family obligations over impartiality. Perhaps it is right in some circumstances but wrong in others. I’ve found my own ethics greatly influenced by the effective altruism philosophy, but my knowledge of moral psychology has led me to become flexible in how I apply the approach.

Ultimately, whether you find effective altruism compelling or not, it might give you pause. The next time you’re about to donate to charity or offer to help someone, it’s worth asking yourself: are you being impartial and helping those most in need – and, if not, why not?